When I first visited South Africa in 2000 to report on the AIDS epidemic there, one adult in five was HIV positive, and a million children had lost one or both parents to the disease. But what really amazed me was that no one was talking about this. Silence gripped the nation like a spell. People with obvious AIDS symptoms told me they were suffering from “ulcers” or “tuberculosis” or “pneumonia.” Orphans said their parents had “gone away” or had been “bewitched” by a jealous neighbor. Now, five courageous teenagers from a Cape Town slum have made a fifteen-minute film called Young Carers: Through Our Eyes about what it’s like to lose a parent to AIDS. It’s one of the most powerful films about the epidemic I’ve ever seen. I hope that audiences in South Africa won’t just feel sorry for these children, but will also examine their own beliefs about the epidemic and its victims.

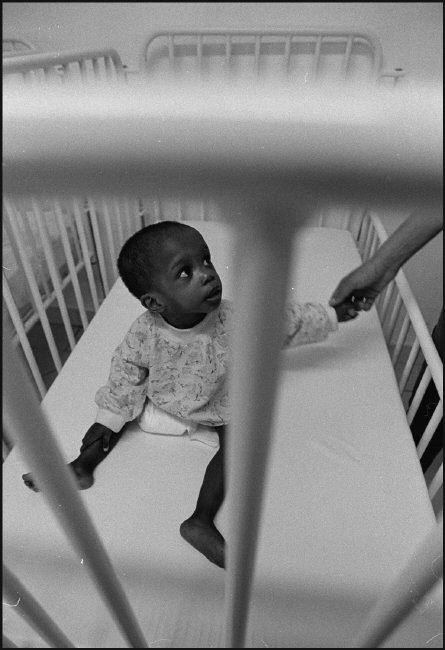

Although the HIV infection rate has finally begun to fall in neighboring countries like Botswana and Zimbabwe, it remains stubbornly high in South Africa. After studying the African epidemic for two decades, I’ve come to believe that shame and silence are the primary reasons, which is why Young Carers is so important. In the film, the five South African AIDS orphans show us images from their daily lives: a brother and sister in parkas sitting on a bed eating porridge; a tooth brushing session in the backyard; an empty refrigerator; a loaf of bread. Some of their families seem to have been somewhat prosperous before disaster hit. Sixteen-year-old Neziswe shows us the concrete frame of the house her mother was building before she died.

Seventeen-year old Phathiswe’s mother also had a steady job once, but when she became bed-ridden in 2008, Phathiswe struggled to buy food for her. “I had to go out and find work for myself,” she explains. Phathiswe longs to become a chartered accountant, but had to drop out of school when her mother, unable to bear the jeers from neighbors who tormented her because of her HIV status, moved back to the rural village where she was born. For me, the most moving scene in this extraordinary little film is when Phathiswe gazes at an empty bed and wonders aloud, through tears, what it’s like to be so sick you can’t do anything for yourself.

Young Carers was conceived by Oxford University professor Lucie Cluver, who has spent the last decade studying the children of AIDS victims in Africa. In 2002, Cluver, then a social worker in Cape Town, was asked by her boss to collect all existing surveys on the mental health of African AIDS orphans. When she found there were practically none, she decided to conduct one herself. Her research demonstrates how abuse and shame perpetuate the spread of the virus. AIDS orphans of both sexes are far more likely than other children—including those orphaned by other causes such as cancer or car accidents—to say they are frequently bullied, pinched, hit, or told they are “lazy,” “stupid,” or “cursed with an evil spirit.” Research from Western countries has found that emotionally and physically abused girls are far more likely to end up in abusive relationships, and Cluver sees the same thing in her study: South African girls from homes affected by AIDS are six times more likely to engage in sex in exchange for gifts or money than girls who have lost parents for other reasons.

The film ends with a call for social grants, food gardens, and free schooling for AIDS-affected children, all of which are obviously important. But watching Young Carers also reminded me of how important artistic expression itself has been in producing the kind of sympathy and open communication that is necessary to fight the epidemic effectively. In the US, for example, almost as soon as the first bulletins about a new disease affecting homosexual men appeared in newspapers in 1981, the gay community rose up against it with paintings, sculptures, videos, novels, poems, and philosophical essays. Gay men and their friends argued fiercely about bathhouses and condoms; they chained themselves to government buildings to protest official inaction and they nursed their dying friends. It’s no coincidence that during this period a huge shift in sexual norms occurred, and HIV infection rates fell by about 80 percent.

This shift was repeated in Uganda, where the HIV rate plummeted by about 70 percent during the early 1990s. I was working in Uganda at that time, and I remember thinking that although the epidemic was different from that in the US gay community, the response was remarkably similar. There were plays, vigils, and marches, and everyone talked about AIDS in highly personal ways. There was vigorous public debate about how men and women treated one another, and even the poorest people cared for the sick and their orphaned children with decency and sacrifice.

Advertisement

Cultural expression through art, protest, or the individual choice to help another person rather than look the other way is an essential response to every human dilemma. Social change may be impossible without it. But why have some societies responded to AIDS with compassion and openness, while others have responded with silence and cruelty? South Africa’s brutal history obviously casts a long shadow over the present day culture, but it’s also possible that South Africans continue to stigmatize people with AIDS because, unlike gay men and Ugandans, they don’t understand how the virus is spreading in their community.

HIV rates are high in this region not because people are especially “promiscuous” in the sense of having many sexual partners, but because they are more likely than people elsewhere to have more than one—perhaps two or three—overlapping long-term partnerships at a time. This “long-term concurrency” differs from the “serial monogamy” more common in Western countries, and the casual and commercial sexual encounters that occur everywhere. But long-term concurrent relationships are far more dangerous, because they link people into a giant network that creates a virtual superhighway for HIV.

Men and women tend to hide these “outside” relationships from one another, which is what makes the lack of openness about AIDS so dangerous. The South African Department of Health and the international donors who support the country’s AIDS programs have done little to help break this silence. As will be announced at the week-long International AIDS Conference, which will take place in Washington DC from July 22 to July 27, the US government has settled on an approach to fighting the epidemic based on treatment with anti-retroviral drugs alone. Meanwhile, virtually all funding for programs to promote awareness of HIV, behavioral change, and compassion for the epidemic’s victims has been sharply cut back. In fact, Cluver was unable to secure funding for Young Carers from any of the dozens of international agencies that collectively spend some $7 billion annually on AIDS programs, and had to finance the film herself. Nearly everyone involved worked for free, and producer Caroline Rupert even had to fashion some of the sound equipment from tin foil.

The rationale for using AIDS drugs to prevent the spread of the virus is based on the results of a single experimental trial of a method known as “treatment as prevention” carried out last year by an international network of researchers funded by the US National Institutes of Health. They set up clinics in various developing countries and recruited hundreds of “discordant” couples, in which one partner was HIV-positive and the other HIV-negative to participate. When the infected partner took anti-retroviral drugs, he was much less likely to transmit HIV to his uninfected partner. While this finding may seem promising, such a program is unlikely to reverse the course of South Africa’s epidemic. For one thing, nine studies have found that nearly all new infections in self-defined “stable” couples in Africa come not from transmission within couples, but from concurrent partners. This was true in the “treatment as prevention” experiment too: all new infections that occurred in the South African couples enrolled in the trial came from “concurrent” partners.

This is only one reason why the currently fashionable “treatment as prevention” programs almost certainly won’t work unless the whole population of South Africa is treated, an unrealistic goal for logistical reasons alone. Other reasons include the risk of increased resistance to drugs, which will vastly escalate costs as well as the frequency of severe side effects, since it will require the use of more toxic second-line drugs. This single minded mass treatment approach, also dubiously known as “combination prevention,” may benefit the pharmaceutical industry, but it isn’t the most efficient use of limited resources, or the most effective way of saving lives. Nor will it circumvent the profound psychological issues raised by Young Carers. Human understanding is the only way out of this crisis, and all the AIDS funding in the world won’t change that.

Young Carers: Through Our Eyes, a film produced by the TAGTeam Teenagers and Caroline Rupert, will be screened at the forthcoming XXIXth International Conference on AIDS in Washington DC by UNICEF’s Regional Interagency Task Team for Orphans and Vulnerable Children and by Save the Children. The TAGTeam are hoping to collect 5,000 messages of support to challenge the stigma experienced by children affected by AIDS. To send a message of support please go to www.youngcarers.org.za, where the film can also be watched online. Viewers can also leave messages for the Young Carers on their Facebook page.

Advertisement