While working in the Anchor/Doubleday art department in the 1950s, the illustrator and writer Edward Gorey discovered a long-forgotten cache of material by an earlier artist, the Krazy Kat creator George Herriman. These were Herriman’s original drawings for Don Marquis’s book about a poetry-writing cockroach and his cat companion, Archy and Mehitabel. In a 1999 interview with Steven Heller, Gorey recalled:

I could scream now, because nobody knew they were there, and I anguished but finally took three of them…. You can’t believe how much stuff there was…you know, old bookjackets from the ’20s, the ’teens. Nobody paid any attention to it.

As Herriman’s drawings aroused Gorey’s impulse to preserve them, so the work of Gorey—who illustrated fifty-odd covers for the Anchor paperback series and would go on to create more than a hundred witty and macabre books of his own—arouses ours today. For the drawings he made throughout his life capture “a whole little personal world,” as Edmund Wilson put it: “equally amusing and sombre, nostalgic at the same time as claustrophobic, at the same time poetic and poisoned.” A number of recent exhibitions and editions of his books suggest a renewed interest in his legacy.

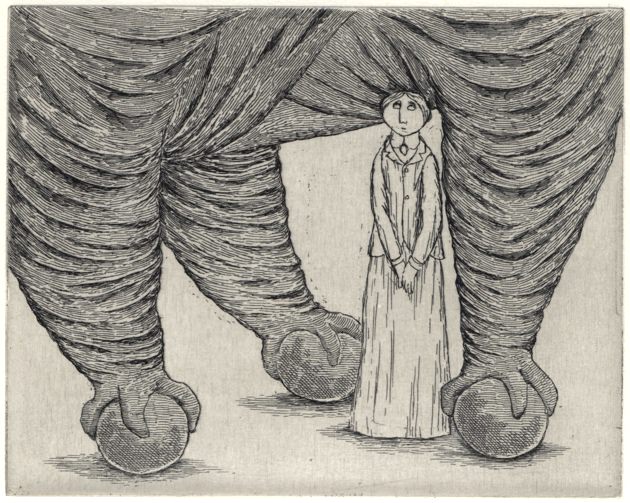

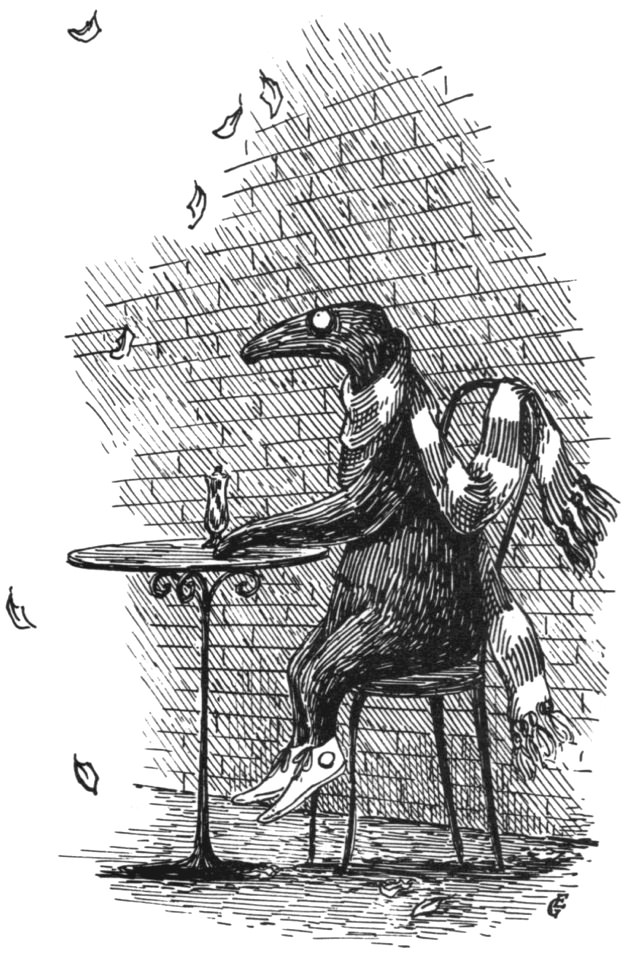

Gorey’s work tends to combine whimsically grim storylines with dour yet dancerly protagonists. Whether they are Edwardian ladies, fur-coated gentlemen, ill-fated children, or unusual animals, his characters are almost always on some kind of journey. His stories often unfold in wallpapered rooms, on barren estates, or among statues, beast-shaped topiaries, and urns. “Few seem to return from the borders to which I’ve sent them,” he wrote to Peter Neumeyer, with whom he collaborated on three children’s books in the late 1960s. (Their correspondence has recently been collected in an absorbing, elegantly illustrated book, Floating Worlds.) Perhaps this is what gives Gorey’s work its talismanic power: his books and drawings, which are so often about imagined deaths and disasters, turn into lucky charms for his readers.

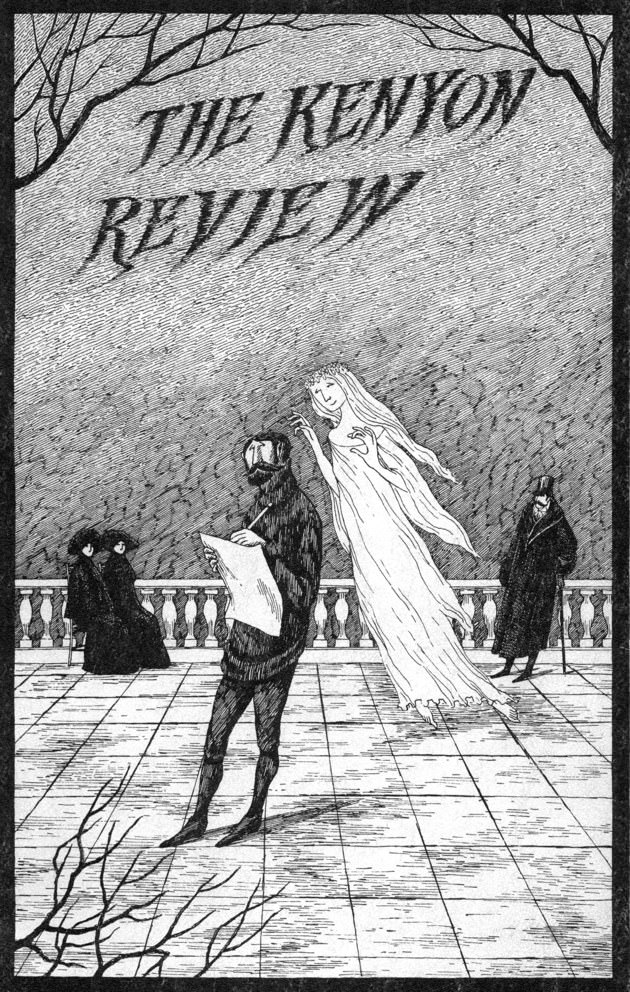

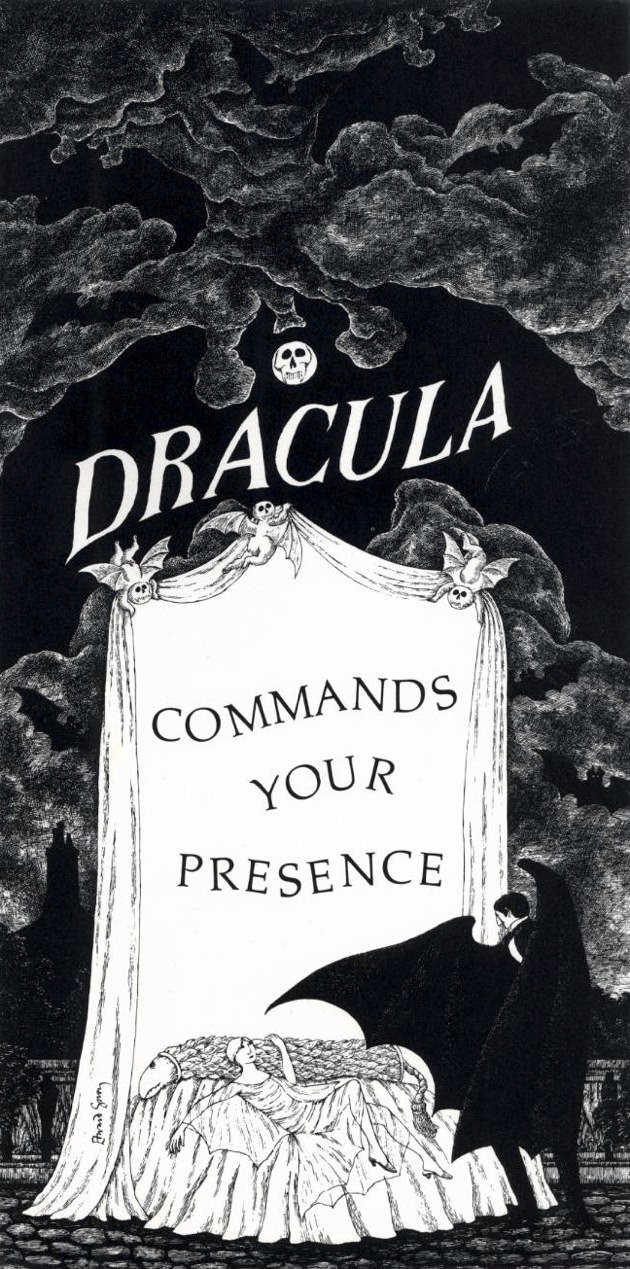

In addition to his own books and his covers for Anchor, Gorey—who died in 2000 at the age of seventy-five—illustrated some sixty books for other writers, including Edward Lear’s The Jumblies, several collections of John Ciardi’s children’s verse, and Muriel Spark’s The Very Fine Clock. Gorey also designed the sets and costumes for a Broadway production of Dracula, illustrated the opening sequence of the PBS show Mystery!, made drawings for the New York City Ballet and the Metropolitan Opera, and for many years drew limited-edition Christmas cards for the publisher and rare books dealer George Bixby, who sent them out annually to his clients (they now often sell for hundreds of dollars apiece).

While many Gorey aficionados own a handful of his treasures, few have amassed a collection as large and comprehensive as that of the architect and attorney Andrew Alpern. The author of nine books of his own, including the Goreyesque Alpern’s Architectural Aphorisms, Alpern spent over fifty years collecting more than seven hundred Gorey-related books and souvenirs and stored them wherever he could in his one-bedroom Manhattan apartment. In 2010 he donated the entire collection to Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library, where more than five hundred of the objects are on display until August 10 in the exhibition “Gorey Preserved.”

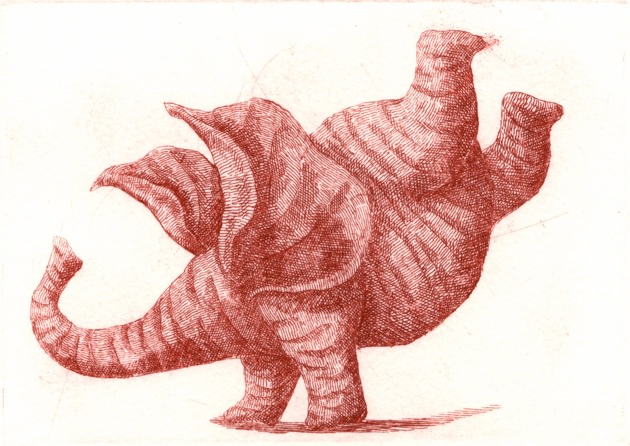

Curated by Alpern himself along with the library’s curator for the performing arts, Jennifer B. Lee, this gloriously overloaded exhibition has the potential to convert even an Aimlessly wandering visitor into a Zealously devoted Gorey fan, and is bound to delight those who already recognize these adverbs from Gorey’s abecedarium The Glorious Nosebleed. It is chock-full of everything from books, postcards, photographs, and newspaper clippings to T-shirts, pot holders, mugs, and plastic party cups—all decorated with Gorey’s illustrations. There are some original drawings, etchings, and prints here as well—including a rare edition of Elefantômas, his set of nine extraordinary elephant collagraphs, which are displayed alongside eleven of his exquisite elephant etchings—but the exhibition’s unmistakable emphasis is on the printed permutations of Gorey’s work and its transformation into a breathtaking trove of tchotchkes.

Take, for example, the case housing Gorey’s artwork for Dracula. Near an original ink drawing of Dracula with a swooning Lucy are photostats of Gorey’s ink and watercolor sketches for the set and costume designs; posters and playbills from the performances; T-shirts, postcards, buttons, and stickers decorated with his drawings; a silver Dracula pendant; several books about vampires with cover illustrations by Gorey; a pop-up book based on Gorey’s sets; a New York Times Magazine article called “Gorey Goes Batty”; and a pair of stuffed-animal bats with thirteen-inch wingspans made out of cross-hatch-patterned cloth. Also included are a newspaper column about a wallpaper pattern adapted from Gorey’s Dracula designs, a magazine advertisement for same, and real samples of the cloth and vinyl damask, inviting visitors to imagine a life within four walls papered with Gorey’s vampiric illustrations.

Advertisement

The rest of the exhibition is nearly as eclectic. But one of its most impressive aspects is that, along with so much ephemera, it includes almost every edition of every book that Gorey wrote and illustrated, both under his own name and under his anagrammatic pseudonyms. Thus visitors can see a first edition of his first book, The Unstrung Harp—which depicts, in Edmund Wilson’s words, “the boredom, the monotony, the impermeable solipsistic confinement of the life of the professional writer”—as well as copies of the French and Japanese versions of The Epiplectic Bicycle, and a section dedicated to what might be Gorey’s most beloved book: The Gashlycrumb Tinies, in which twenty-six children with names from A to Z die in twenty-six different ways: by awl, by brawl, by ennui.

Especially tantalizing are several rare letterpress editions of Gorey’s miniature books, The Eclectic Abecedarium and QRV (each a rhyming verse homage to moral primers of earlier centuries), complete with tiny slipcases smaller than matchboxes. Also on display are almost-as-rare editions of Gorey’s Exquisite Corpse–like books, including Les Échanges Malandreux, whose pages of drawings and text are cut into strips that can be mixed and matched to create different creatures and tell different stories. One longs to open them up and play with the possible combinations. Luckily, this will be possible for visitors to the library once the books have been catalogued and rejoin the permanent collection.

Gorey treated language playfully in all of his texts, hand-lettering the type, and he created many illustrated alphabet books, several of which are in the exhibition. Not on display is a particular favorite, one of his “thoughtful alphabets” called The Deadly Blotter, whose plot races forward letter by letter, from “Alarming behaviour” to “Corpse” to “Detective enters.” Instead of his usual finely detailed cross-hatching, Gorey used dense blocks of black and white for these illustrations, creating lean characters who drape themselves over drawing-room furniture and point their fingers in all directions while offering “Helpful irrelevancies” and “Likely motives.”

Another of Gorey’s magical word creations is his “Interpretive Series” of Dogear Wryde postcards, devoted solely to the letter I. All thirteen cards are elaborately displayed in the exhibition, giving viewers a chance to take pleasure in Gorey’s drawings of a lizard-like beast enacting “Inquisitiveness,” “Indolence,” “Inconstancy,” “Ineptitude,” “Inanity,” and eight other mostly unflattering nouns. It’s hard not to be smitten with these playful postcards, each of which was hand-painted by Gorey after being printed.

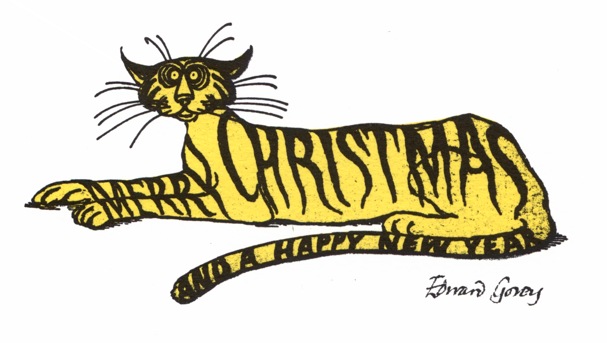

Animals, both real and invented, live large in Gorey’s work, perhaps none more so than his cats. Gorey loved cats at least as much as he loved the ballet—for thirty years he spent half of each year in Manhattan during ballet season—and his anthropomorphic renderings of them are everywhere in the exhibition: peeking out from his books, posing on buttons for the “New York Kitty Ballet,” relaxing contentedly on a cat-patterned cravat, and emerging into being in a charming sketch from one of Gorey’s notebooks (on loan from the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust). “Cats share with ballet dancers the quality of graceful movement,” Gorey told Cats Magazine in 1978. “As an artist, I find their expressions endlessly and frustratingly fascinating.” Perhaps this is why most of his cats wear bewitching smiles; whether they are standing atop a unicycle or leaning against a gravestone, they seem carefree and sprightly, in happy contrast to Gorey’s more Gothic creations.

Gorey contributed a number of drawings to The New York Review of Books, including original artwork for every anniversary cover from 1978 to 1998 (two years before he died). None of them appear in “Gorey Preserved,” but many of the clippings are preserved in Alpern’s scrapbooks. Especially noteworthy is Gorey’s Les Mystères de Constantinople: La Malle Saignante, a farcical romp whose characters include a young leading lady, a baron, an ambassador, an alligator, and Ahududu, an unlikely villain apparently carved from wood. It was serialized in the Review in 1975; its heroine, according to Gorey’s close friend Alison Lurie, “was thought by some to resemble one of the NYR’s editors.”

It may surprise Review readers and Gorey fans alike to learn how far back his link to the magazine’s founders goes. Gorey first met the Review’s co-founding editor Barbara Epstein—who died in 2006—in the late 1940s, when he was at Harvard and she was at Radcliffe; and as a young editor at Doubleday in the early 1950s, she and her future husband, Jason Epstein, another founder of the Review who was then launching the Anchor paperback series, invited Gorey to work in the art department. Barbara Epstein recalled Gorey’s Anchor cover illustrations to Stephen Schiff in a 1992 New Yorker profile: “They were beautiful, ravishing. He worked very slowly, with a tremendous perfectionism, and he would never let a drawing out of his hands if it was less than perfect.”

Alpern’s Gorey collection began in about 1957 with one of those Anchor books: André Gide’s novel Lafcadio’s Adventures, whose cover was the first that Gorey illustrated for the series. Around the same time, Alpern bought Gorey’s second published book, The Listing Attic, a set of illustrated limericks. However, it was in the mid-1970s that his efforts became systematic. On a visit to the Gotham Book Mart in Midtown, Alpern bought a little book of Gorey’s on sale by the cash register. Andreas Brown, the bookstore’s owner, began to let Alpern know when Gorey would be making appearances at the store, where Brown frequently exhibited his work, and from then on, Alpern bought every new book that Gorey published, along with special editions of etchings and other artwork—as well as every Gorey-illustrated curiosity that came along.

In 1980, Alpern joined with George Bixby in an act of true collectors’ devotion to produce a limited edition of Gorey miscellanea. They gathered together an eclectic set of Gorey’s one-of-a-kind illustrations in a clamshell box, typed out a contract for him to sign, and asked him what to call the collection. Gorey spontaneously titled it, with the sound of the word “ephemera” in mind, FMRA—writing the letters down on a piece of paper for his enthusiastic publishers.

Today a growing number of Gorey cognoscenti are working to keep Gorey’s work permanently in print and in the public eye. More than fifty of his books and miscellany are currently available from Pomegranate, which plans to release new editions of The Osbick Bird and Thoughtful Alphabets: The Just Dessert & The Deadly Blotter this fall; and New York Review Books has also brought some of his collaborations back into print. Drawings from his archives continue to appear in magazines like the Review, in articles ranging from contemporary fiction to the Internet. Several Gorey-lovers have posted digitized versions of his books on YouTube.

Pomegranate

An envelope that Gorey sent to Peter Neumeyer in 1968, introducing characters for their 1970 book Why We Have Day and Night (from Floating Worlds)

Meanwhile, in addition to “Gorey Preserved,” at least two other Gorey exhibitions are now on view: “Elegant Enigmas: The Art of Edward Gorey,” at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach (which features a substantial number of original drawings and is accompanied by a wonderful catalog); and “Edward Gorey’s Envelope Art,” at the Edward Gorey House in Cape Cod (which includes some of the envelopes he sent to Peter Neumeyer). Andreas Brown, who is now a representative of the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust, has been helping Gorey’s collectors find institutional homes for their valuable holdings—one or two even larger than Alpern’s—so that they will be archived and made accessible to scholars and the public. Gorey’s own enormous library of some 25,000 books has been acquired by San Diego State University, which already holds a rich collection of Gorey material and hosted a major exhibition of his work in 2004.

Shortly after Gorey’s death, Alison Lurie—to whom Gorey dedicated one of his most enchantingly discomfiting tales, The Doubtful Guest—wrote, “Often, characters in Gorey’s books who die or disappear leave only a void behind: empty cross-hatched streets and withered formal gardens and rooms with strange wallpaper.” But for Gorey fans and addicts—who, with all this Goreyana now abounding, will have mounds of material to admire for years to come—Lurie’s closing words ring true: “We are luckier.”

“Gorey Preserved” is on view at Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library in New York City until August 10, 2012.