During the spring of 2010, when Marina Abramović’s retrospective, “The Artist is Present,” was on view at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, it sometimes seemed impossible to open a magazine or newspaper without reading about the artist and her show. I remember feeling curious, admiring, and vaguely irritated. Why, with so few hours in the day, was I spending even five minutes wondering about whether Abramović was exploiting the artists who had volunteered to serve as her apprentices and to reenact (in most cases naked) some of her most physically demanding performance pieces?

I went to see the exhibition and its eponymous centerpiece: the artist, seated in a chair in the museum’s atrium, gazing intently, immobile and in silence, at the audience members who came, one by one, to sit opposite her. As I watched from the sidelines, I ran into a friend I hadn’t seen for a while. We chatted about our work, exchanged news of family and friends. Then I left, glad to have seen my friend, but otherwise no more affected by the Abramović show than I had been when I arrived.

So I was surprised and pleased—as I usually am when something persuades me to reconsider an overly hasty judgment—to watch Matthew Akers’s documentary film, Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present, and to realize how much I’d failed to comprehend. Some of what I’d overlooked seems, in retrospect, obvious: spending months in a hard chair, staring at a succession of strangers, was no less punishing and painful than earlier Abramović works which had involved self-mutilation and physical danger. But though I’d read about the intense responses of so many of the visitors who came to experience the artist’s presence, I didn’t—and perhaps couldn’t, unless I’d stayed around for as long as Akers did—register them in my own brief visit to the show.

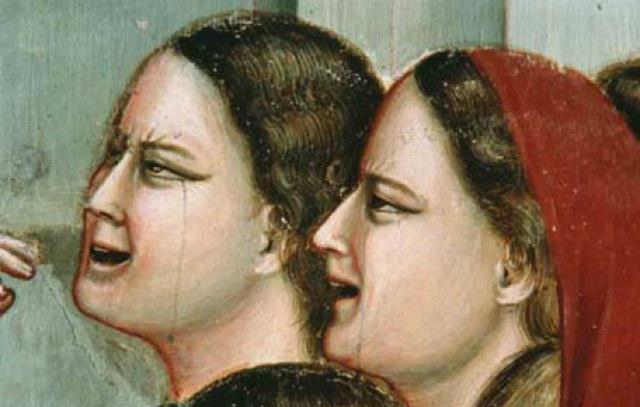

Somehow it had escaped my notice that sitting across from Abramović in the museum atrium was, for some, a quasi-religious occasion. As the film carefully records, people wept, and responsive tears welled up in Abramović’s eyes. One man had the number of times he’d sat—21—tattooed on his forearm. Watching the film, I was reminded of the pilgrims who, centuries ago, traveled to see (and perhaps have their lives changed by) the ascetic saints who—perched on poles, dwelling in caves—claimed to have found God in discomfort and (at least when the pilgrims weren’t there) solitude in the desert.

By the time I saw the documentary, the hype and publicity surrounding the show had subsided. I was conscious of the contrast between the way I experienced the film—on TV, in the peace and quiet of my apartment—and the circus-like atmosphere of the exhibition itself. And I realized that, for at least some of those viewers who gave themselves over to their silent communion with the artist, the experience seemed to have been one of great intimacy; somehow able to ignore the presence of large numbers of onlookers, they might as well have been secluded with Abramović in a desert cave.

Art can, of course, do many things: dazzle us with its energy, its originality, its technical virtuosity; amuse, unsettle, or outrage us; comment on the culture in which we live; give us pleasure and provide us with intimations of mysterious beauty. It can touch us in ways that transcend the limitations of language. But quite aside from the question of aesthetic merit, less and less frequently does contemporary art do what “The Artist is Present” appears to have done—to inspire its viewers with anything approaching an extreme emotion.

In part this may have to do with the way we experience art. By nature, reading, for instance, is a highly private event—the mind of the reader communicates silently with the mind of the writer—while theater (or so producers and actors hope) is necessarily a communal one. But visual art can be either, though we learn, or try to learn, to transcend the distractions of seeing art in a crowd. Of course, performance art is intended to blur the division between visual art and theater; in “The Artist is Present” Abramović found an innovative way to combine the private experience (sitting across from her) with the public one (watching others sit across from her).

This summer, in Florence, I was reminded that visiting a mobbed gallery can transform masterpieces into sources of claustrophobia and annoyance. Occasionally one hears that museums still employ guards to assist visitors who, overcome by “Stendhal Syndrome,” are moved to faint by their proximity to great art. But though Stendhal coined the term after a visit to Florence, the syndrome’s victims there now run the risk of being trampled before rescue can arrive. If it seems more likely that one might faint from the suffocating heat and the oppressive crowds than from an aesthetic pleasure, surely that too indicates something about the ways in which our experience of art has changed since Stendhal’s time.

Advertisement

I’ll never forget spending an hour in a dimly but perfectly illuminated gallery of the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, looking at Caravaggio’s The Flagellation of Christ. Would I have been so profoundly moved if busloads of visitors and chatty docents had appeared to alter my sense that Caravaggio had something to say to me, and me alone, about the human capacity to endure and inflict suffering? Unlike his secular paintings, commissioned for the private collections of patrons, Caravaggio’s biblical scenes were—like much of medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque religious art—intended for churches where they would instruct and move the public, and reconfirm the pious in their faith. But a visit to Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel in Padua—where, for reasons having to do with conservation and preservation, one approaches the frescoes through a series of air-lock chambers and can stay only for a closely monitored and strictly timed interval—demonstrates how even the greatest religious art, seen under unpleasant and dehumanizing circumstances, can make us wish we were home, calmly paging through a book of reproductions.

In an era of biennales, art fairs, and blockbuster shows, we cannot really allow ourselves to forget where we are unless we are in fact alone—or, like a man I saw once at a gallery, studying the paintings through two holes punched in a shoebox designed to screen out everything around him but the art on the walls. If we move too close to a painting, we can be sure of hearing the warning admonition of the museum guard, an automated alarm, or the complaints of other visitors whose view we are blocking. Such wariness cannot help but limit our ability to fully engage with the art.

This may be part (but only part) of why it has become so rare to see art lovers overcome by emotion—as they clearly were at the Marina Abramović show. It’s easier to understand, and more common to observe, the effect of religious art on people of faith (once I saw a young priest kneeling and weeping in front of a fresco depicting the Crucifixion in Rome’s church of San Clemente) and the emotive force of work by painters, such as Van Gogh and Arshile Gorky, who have become martyred saints of art. In addition, there are artists—Mark Rothko being one example—who, regardless of their original intention, have become religious painters; I’ve observed visitors deep in meditation in the Rothko Chapel in Houston, soothed by the blurred bands of color in ways that one cannot quite imagine occurring in front of one of de Kooning’s women—which may inspire a whole other host of responses besides prayerful tranquility.

Some of our most visible painters—John Currin would seem an obvious case—appear more interested in eliciting a knowing irony than in making us burst into tears or fall to our knees. Not long after the Abramović exhibition closed, I watched, with horrified fascination, a reality TV series entitled Work of Art, in which young artists were invited to compete, as in a cooking-contest show, and have their creations critiqued by a panel of judges. I don’t remember the critics once referring to an emotion—or the lack of one—inspired by the works of view. The emphasis, as I recall, seemed to be more on conception, execution, and in the contestants’ potentially successful art careers. As much as I admire and can find pleasure in the formal beauty of Brice Marden’s calligraphic evocations of Eastern art, I have yet to see anyone in tears in front of one of them. And though, in the late 1980s, I met a guy who had a brightly colored Keith Haring baby tattooed on his forearm, I was given to understand that this was a political statement, a personal response to the AIDS crisis, and not an aesthetic one.

In 2009, the same atrium in which Abramović appeared hosted an installation by the artist Song Dong entitled “Waste Not.” Its title was taken from a communist government slogan exhorting the Chinese to cope with shortages by saving everything, no matter how insignificant. After the death of his father, in 2002, Song Dong and his mother collaborated on a project that utilized the astonishing collection of ordinary household objects she had hoarded. The resultant maze of artifacts and detritus—buttons, cooking utensils, ribbons, shoes, bottles, toothpaste tubes, hair brushes, and gramophones—was an immensely touching statement about family, time, memory, about what can be saved and what will inevitably be lost. The aisles dividing the objects were too narrow to accommodate crowds, and in any event the show seemed (certainly compared to the Abramović exhibition) under-publicized and under-attended. Progressing through the labyrinth, one felt that one was being shown something at once powerful and revealing about Song Dong’s family, his country, his history—and reminded of one’s own experience of childhood and domestic life, of everything we save and lose as we leave home and, like birds, build new nests, often from scavenged materials. It was one of the few works of visual art that I can recall, in recent years, moving me as deeply as an emotionally engaging book, film, play, or piece of music.

Advertisement

Of course, the evocation of feeling, on its own, is no indicator of merit. Nor are the most powerful responses always elicited in intense personal communion with a work of art. If the ability to touch large numbers of people were the principal measure of aesthetic value, then Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will would suggest that Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, was the greatest artist of the last century, and that his design for the Nuremberg Rally was his masterpiece.

What I understood when I watched the film documentary of “The Artist is Present” was not only what Marina Abramović had attempted and accomplished—but what her audience had so desperately wanted and found when they faced her, in an uncomfortable chair. Some, it was clear, had traveled long distances to commune with the artist, though perhaps not as far, or so arduously, as those who tour Donald Judd’s converted army base in Marfa Texas, or those who visit the Great Salt Lake to see Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty.

Is what these art-lovers are seeking so different from what the pilgrims hoped to discover when they journeyed into the desert to distract St. Simon Stylites and St. Anthony from their meditations? Is it any wonder that so many sought a few minutes of transcendence by staring into the eyes of an artist whose sole mission, during those months, was to register their presence, to sit there, and look back?

The faithful who came to meditate on a fresco of Giotto’s or a painting by Caravaggio sought a personal experience of the divine, the feeling that they themselves were present, witnessing the mystery being represented, a miracle that was being enacted specially for them. At the MoMA show, the artist’s presence offered transcendence through communion and intimacy, in the privacy that Abramović was able to create in a crowded atrium. Watching the documentary, I thought: This is the moment in which we live. Alienated, unmoored, we seek our salvation, one by one, from the artist who brings us the comforting news: I see you. I weep when you weep. The mystery, and the miracle, is that you exist.

Matthew Akers’s documentary Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present is playing at selected theaters across the United States this fall.