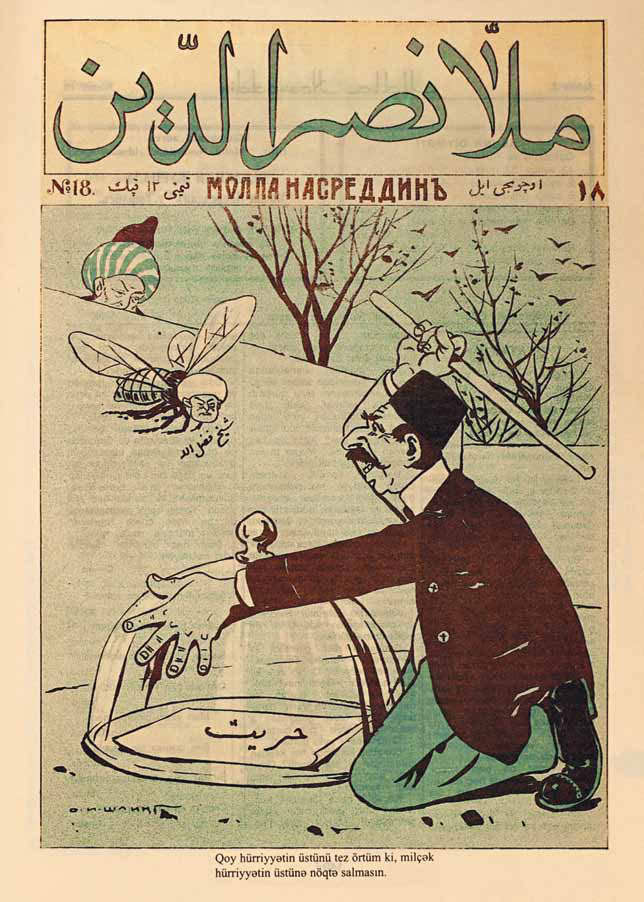

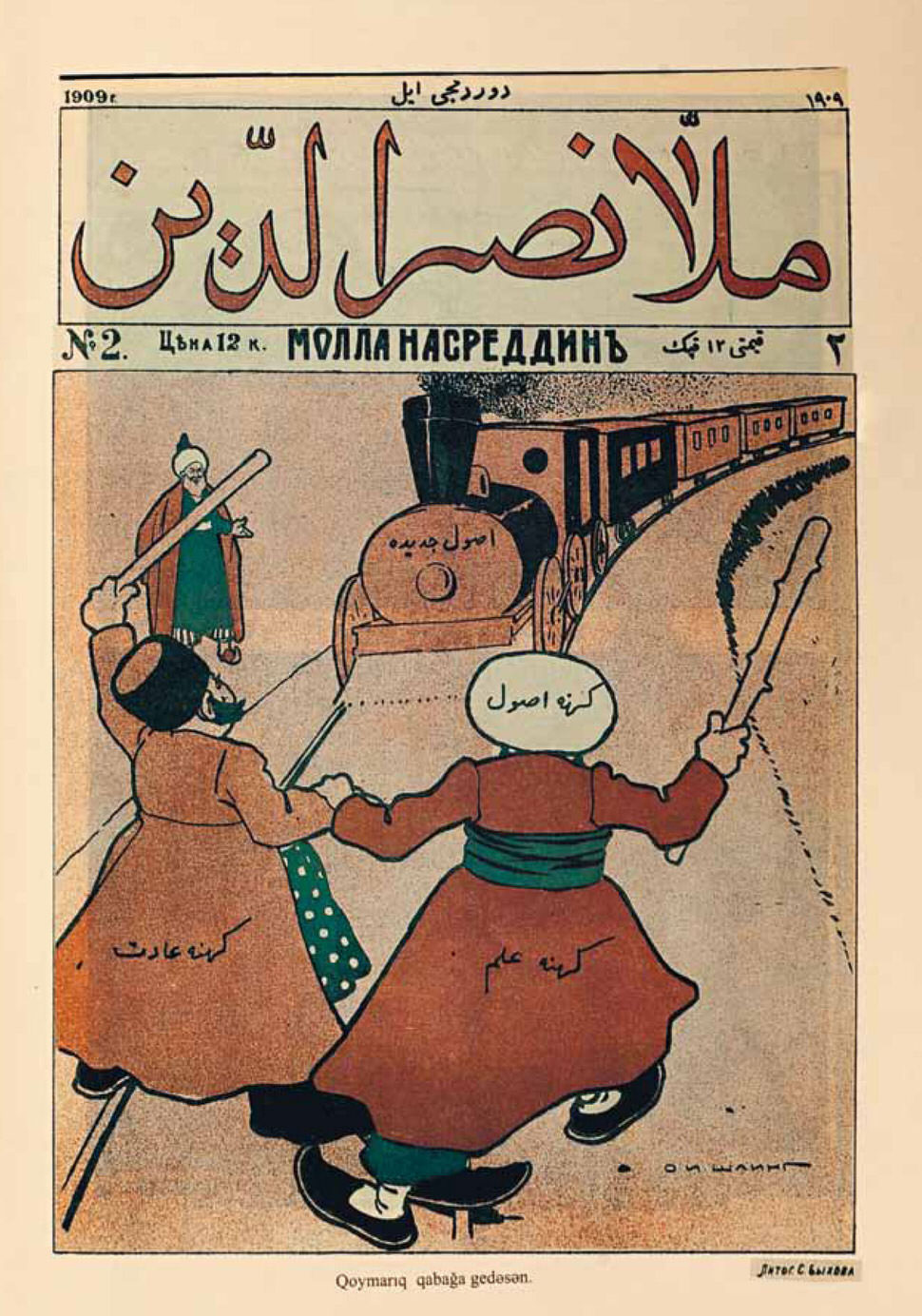

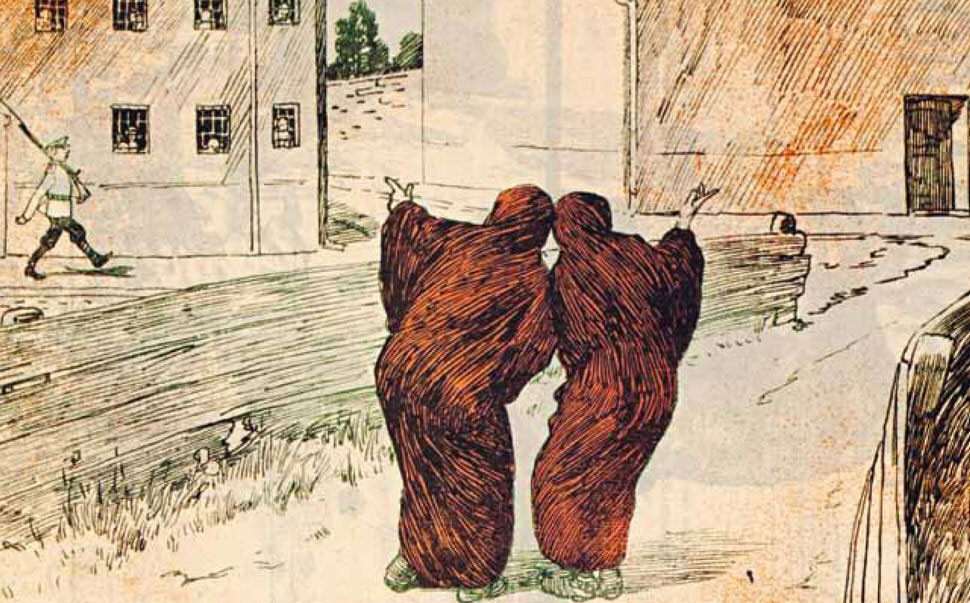

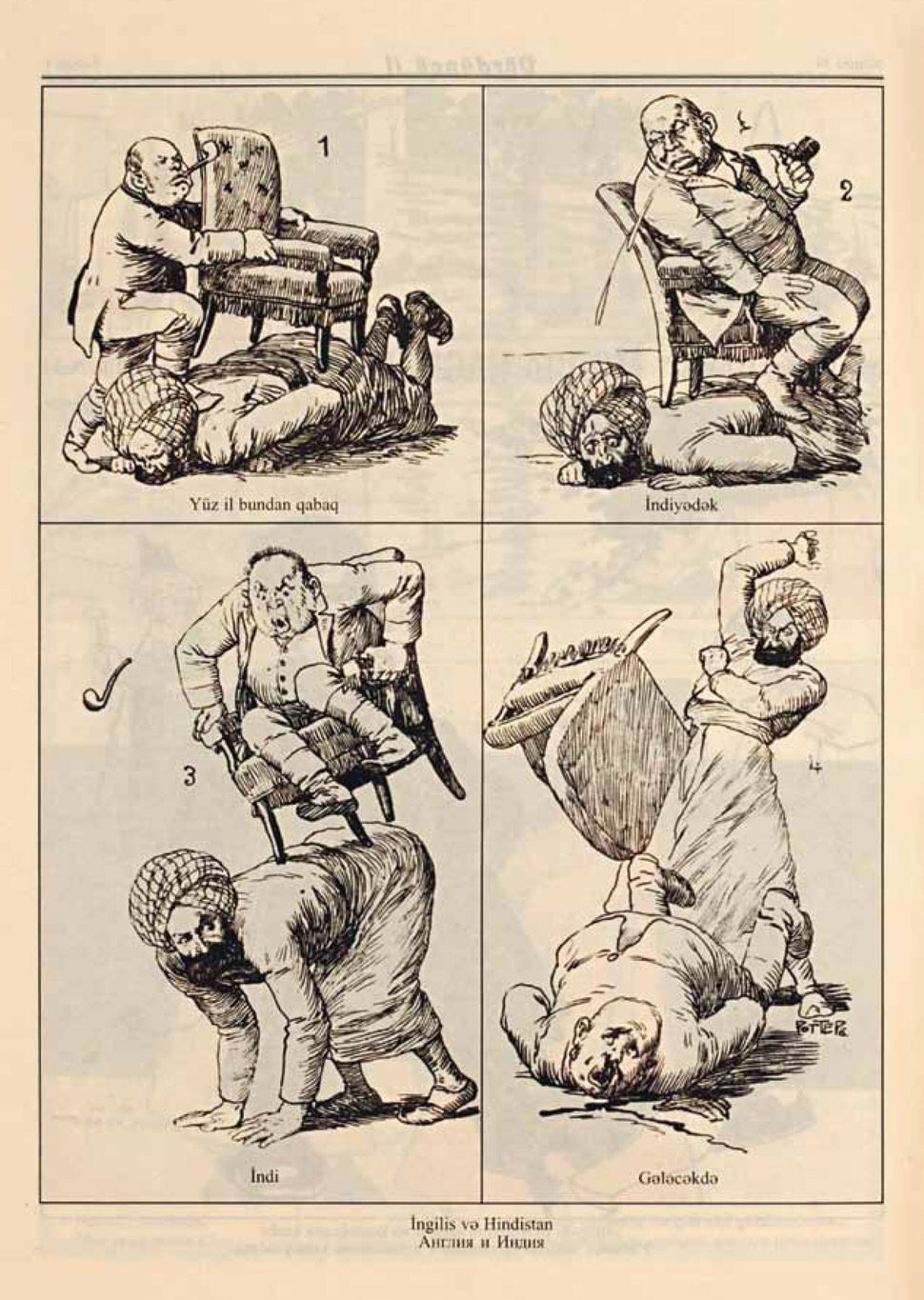

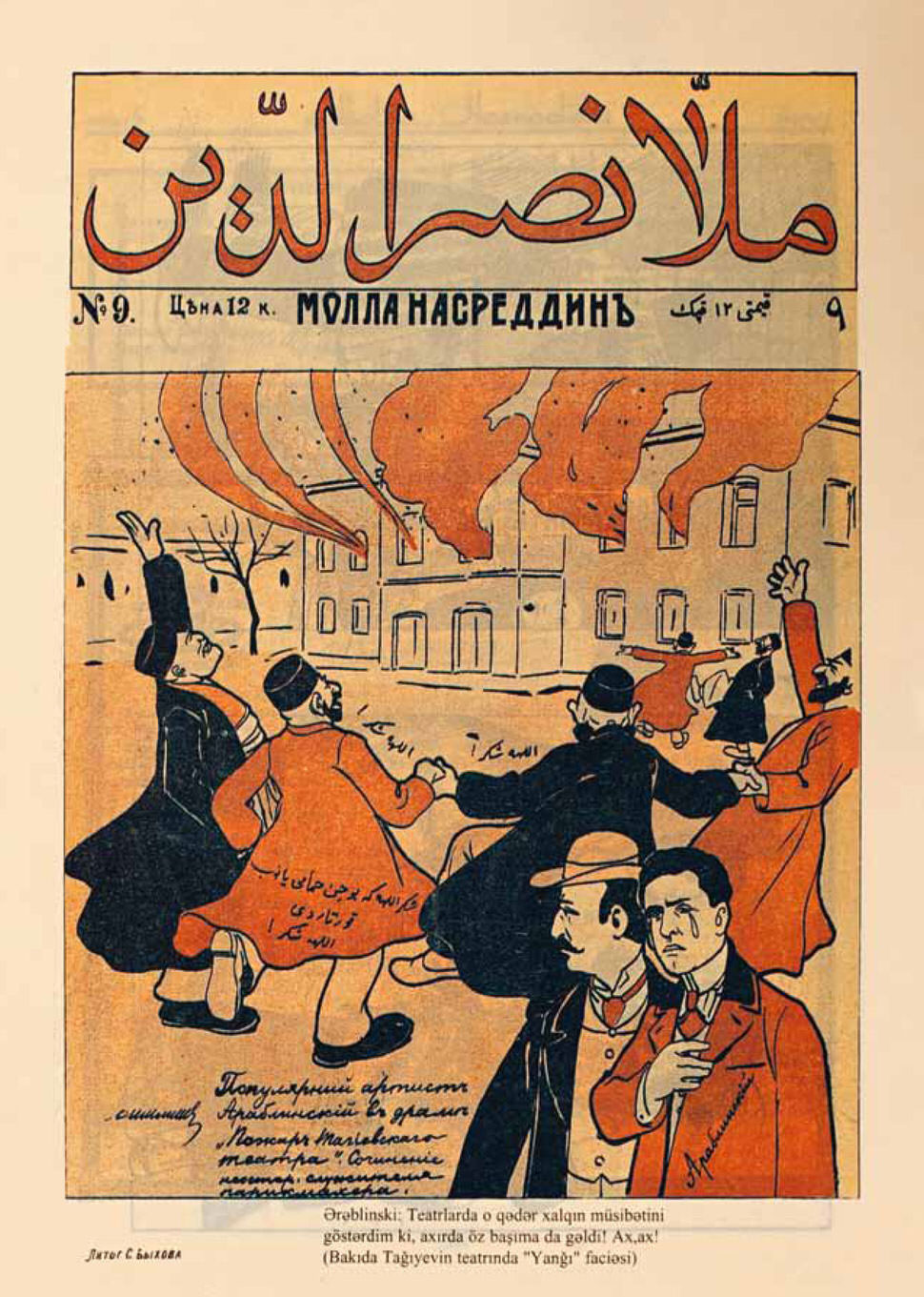

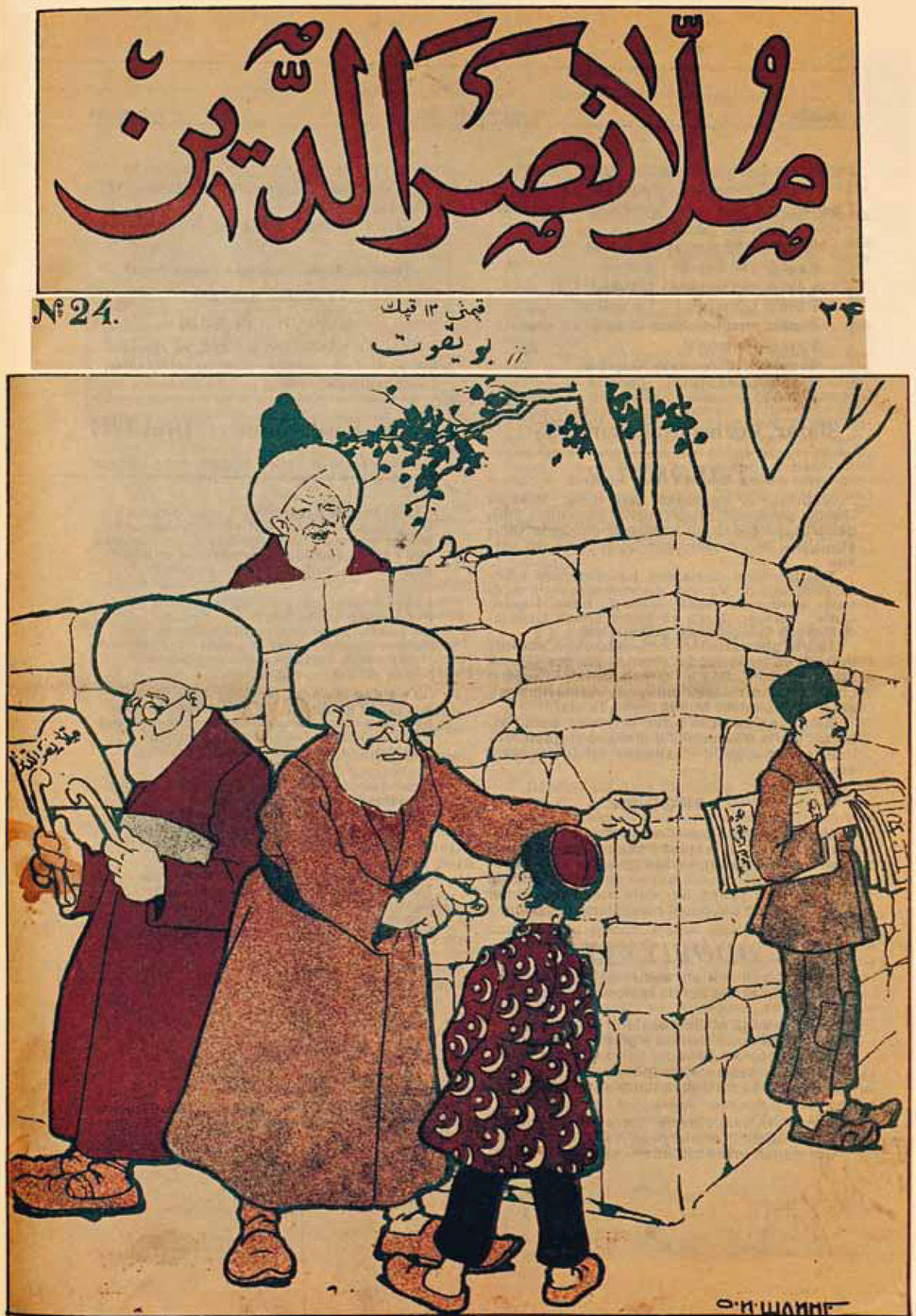

Published between 1906 and 1930, Molla Nasreddin was a satirical Azeri magazine edited by the writer Jalil Mammadguluzadeh (1866-1932), and named after Nasreddin, the legendary Sufi wise man-cum-fool of the Middle Ages. With an acerbic sense of humor and realist illustrations reminiscent of a Caucasian Honoré Daumier or Toulouse-Lautrec, Molla Nasreddin attacked the hypocrisy of the Muslim clergy, the colonial policies of the US and European nations towards the rest of the world, and the venal corruption of the local elite, while arguing repeatedly for Westernization, educational reform, and equal rights for women. Publishing such stridently anti-clerical material, in a Muslim country, in the early twentieth century, was done at no small risk to the editorial team. Members of MN were often harassed, their offices attacked, and on more than one occasion, Mammadguluzadeh had to escape from protesters incensed by the contents of the magazine.

Managing to speak to the intelligentsia as well as the masses, however, the magazine was an instant success and would become the most influential and perhaps first publication of its kind to be read across the Muslim world, from Morocco to India. Roughly half of each eight-page issue featured illustrations, which made the magazine accessible to large portions of the population who were illiterate. And like the best cultural productions, MN was polyphonic, joyfully self-contradictory, and staunchly in favor of the creolization that results from multiple languages (it drew on three alphabets), ideas, and identities (its editorial offices were itinerant between Tbilisi, Baku, and Tabriz). While it helped give rise to a new Azeri intellectual culture, Iran was arguably the country where it had its greatest impact: MN focused relentlessly on the inefficiency and corruption of the Qajar dynasty, and its essays and illustrations acted as a preamble of sorts to the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1906-1910, which resulted in the establishment of the first parliament in all of Asia.

During Molla Nasreddin’s two and a half decade run, the country at the heart of its polemics and caricatures—Azerbaijan—changed hands and names three or four times. By 1920, the Soviets had invaded Baku; the quality of the magazine’s editorial and art-direction suffered considerably as it was forced to toe the Bolshevik party line. Only three issues came out in 1931 and shortly afterward it shut its doors for good. Its impact, however, is difficult to over-estimate. Molla Nasreddin offered inspiration to similar pamphleteers from the Balkans to Iran and Serbia. The Azeri newspaper Irshad coined the term “Molla Nasreddinism” to describe the ability to tell things as they are.

Adapted from Slavs and Tatars Presents: Molla Nasreddin: The Magazine That Would’ve Could’ve Should’ve, published by JRP-Ringier, Zurich. A new installation by Slavs and Tatars, Beyonsense, is on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York through December 10.