Vaka Valo

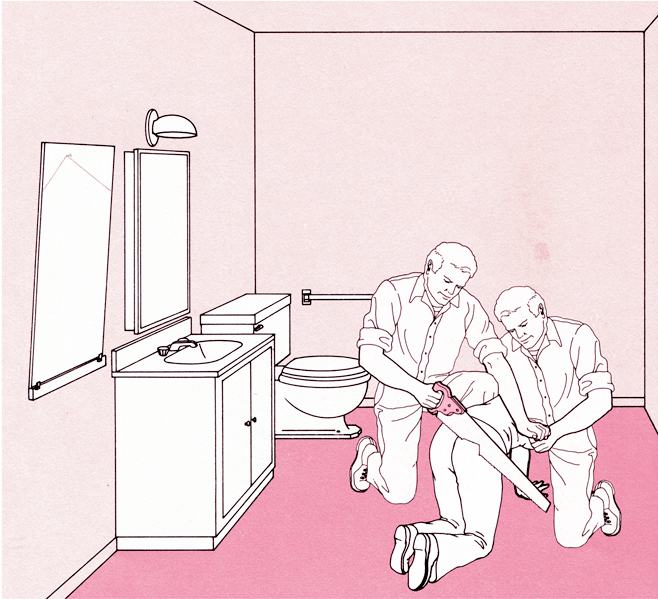

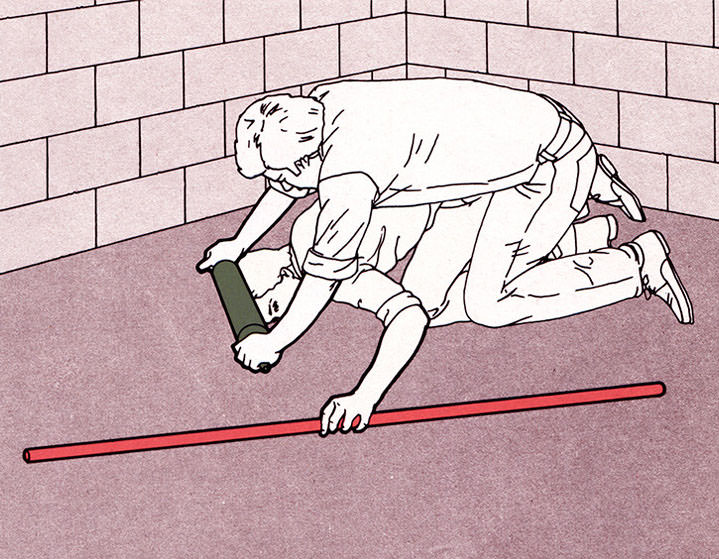

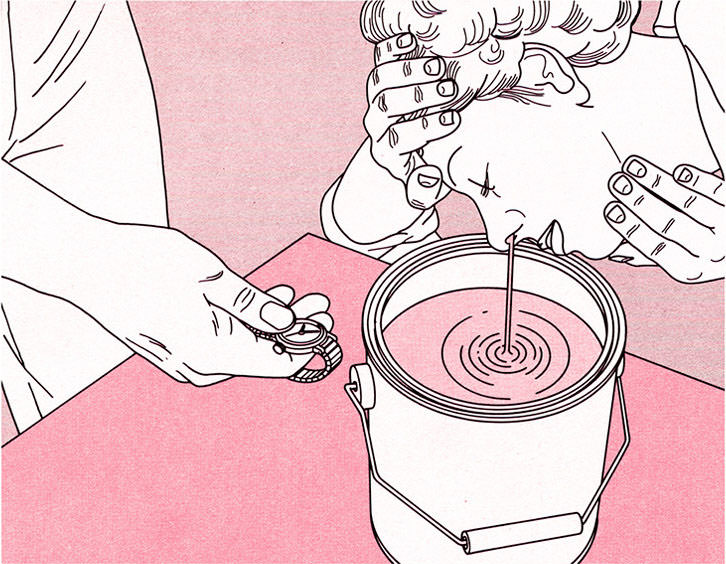

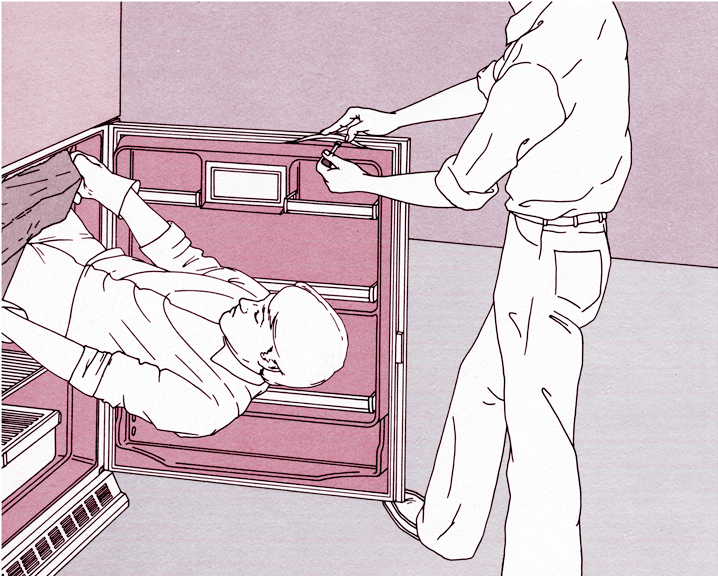

Vaka Valo: Dream Diary No. 10, 2009.

Valo’s continuing “Dream Diary” print series can be viewed at vakavalo.com.

Everyone has dreams. Some remember theirs, far fewer recount them, and very few write them down. Why write them down, anyway, knowing you will only sell them out (and no doubt sell yourself out in the process)? I thought I was recording the dreams I was having; I have realized that it was not long before I began having dreams only in order to write them.

The Dentist

At the end of a maze of covered walkways, a bit like in a souk, I arrive at a dentist’s office.

The dentist is out but her son, a young boy, is there. He asks me to come back later, then changes his mind and tells me his mother will be back any moment.

I leave. I run into a tiny woman, pretty and cheerful. It’s the dentist. She leads me to the waiting room. I tell her I don’t have time. She opens my mouth very wide and bursts into tears as she tells me that all my teeth are rotten but that it’s not worth treating them.

My mouth, open wide, is immense. I have an almost palpable sensation of total rot.

My mouth is so large, and the dentist so small, that I suspect she is going to put her whole head in my mouth.

Later, I run through the shopping mall. I buy a three-burner gas stove that costs 26,000 francs and a 103-liter refrigerator.

—No. 5, December 1968

The Switch

“One fine morning,” I am once again in a concentration camp. It’s time to get up; the challenge is to find clothes (I am dressed in everyday attire, tweed jacket, English shoes).

In the camp, everything is for sale. I see rolls of large bills in circulation. The guardians give potions to the detainees.

Someone finds me a jacket. We line up to go down (we’re in a large dormitory on the second floor of a sort of repurposed barrack).

We hide for a moment in a hallway.

We walk in quadruple file. An officer lines us up with a long bamboo switch. He is kind at first, then suddenly he begins to insult us horribly.

In line for roll call. The officer is still shouting but not striking anyone. At one point, each of us (he and I) is holding an end of the switch; I am overcome with panic at the prospect of him hitting me.

The universe of the camp is unbroken: nothing can be done to affect it.

Later, I burst into tears while passing a tent where children with an incurable disease are being treated. Their only chance of survival is here. I wonder if this survival doesn’t consist in their being turned into pills, which reminds me of an anecdote about dieting cures that work because the dieters are told to ingest pills that actually contain a tapeworm.

—No. 17, July 1970

The Epidemic

The dreamer (this whole story is like a novel in the third person) has sat down at a little bistro. He is foreign, but they quickly come to treat him like a regular. The boss and some of the customers are discussing the epidemic. The Chinese cook of the restaurant enters (the dreamer thinks he looks like someone he knows); the Chinese cook says they need to find a replacement for him, because he can no longer continue to man the stoves and cook for the girls. On this note he cites a Shakespearean proverb:

They died not all, but all were sick!

Stunned, the owner of the café looks at the dreamer: he’s the one who taught him the proverb. At that instant the dreamer understands that he is no longer a stranger at some table and that he is now the “central character”; at the same time, he recognizes the Chinese cook; he knows only him; he’s the one who comes from time to time to volunteer for the girls.

There has been a great cholera epidemic. Everyone wants to be examined. The symptom is spitting up blood. The dreamer and two of his friends walk around the town. They arrive in front of a stairway blocked by a mass of young girls, surely a boarding school. They pretend to have priority, like one of them has been stricken, so that the doctor has to look after them first. The doctor has to clear a path through the girls.

A bit later, in a crowd of girls splayed out, sick, the dreamer picks up a piece of earth (and not a piece of trash or of feces) from the ground. And he discovers, behind a door, his friend J., laid flat, dead, turned into earth, turned into a block of earth that is missing the piece the dreamer just picked up.

Advertisement

—No. 28, October 1970 (Neuweiler)

The Vendor

I have killed my wife and cut her rather crudely into small pieces, which I have wrapped hastily in paper bundles. The whole of her fits in a cardboard box, which is still relatively easy to handle.

My only hope is for someone to make her into wine or alcohol. I go to the distillery. I walk without knocking into a room where there are three women in overalls. Two are sitting down, the third is standing near a waist-high double door (like a saloon door).

Either I address them with a wink, like we know one another, or I call out, flatly, something like:

“I have 50 kilos of quality meat!”

The young woman who was standing brings me into a tiny room, where she begins to examine my merchandise. My package has all the necessary labels, but the young woman claims that the firm I represent is not an approved client of her Company and that I’m going to have a hard time closing the deal.

As a sample, I take a series of small bottles from the package. This should be no more than a simple formality, but, to my great confusion, there are more and more bottles: red wine, white wine, rosé, all sorts of liquor, even a pitcher of water—tiny, but full and above all uncorked: you could dip a finger in without making it overflow, which strikes me as an indubitable experimental demonstration of osmosis or of capillarity.

All the demonstration proves useless: a man comes out from the office next door and tells me this will end badly for me if they don’t find my name in their files.

—No. 77, July 1971

These excerpts are drawn from La Boutique Obscure: 124 Dreams by Georges Perec, translated by Daniel Levin Becker, to be published by Melville House on February 19.