I used to think that it was a bad thing to mention dreams in fiction. I’d read an essay by John Leonard, I believe it was, in The New York Times Book Review sometime in the late Seventies, in which he said that dreams in novels were a mistake. But I rejected that notion ages ago. Dreams are part of the truth of life and the job of a book is to feel its way forward through a character’s days and nights. In the book I just finished writing, I included a dream in which my narrator finds an old bicycle horn on a set of subway stairs somewhere near Columbia. Why not? It’s a dream I actually had a few years ago.

The letter O is a good dream letter. It begins the word “oneiric,” which is a dark interesting sharp-edged word that college professors used to use in class in place of “dreamlike.” I used to dream fairly frequently and oneirically that my mouth was full of masses of unchewable, exhausted, flavorless chewing gum. I realized that what I was dreaming about was my own boring tongue. I wrote about this dream in a novel and because I wrote about it, the dream stopped recurring and I missed it.

Just a few days ago, I had an unpleasant dream. In it my knee hurt. I looked down at my leg and discovered that a flap of recently healed tissue, including my entire kneecap, was hanging off my leg, attached to it by a narrow isthmus of tender flesh. I decided that I had to cut off this growth with a pair of scissors. That didn’t go well. When I woke up, I realized what the problem was: my leg had been at an odd angle in the bed, and it hurt.

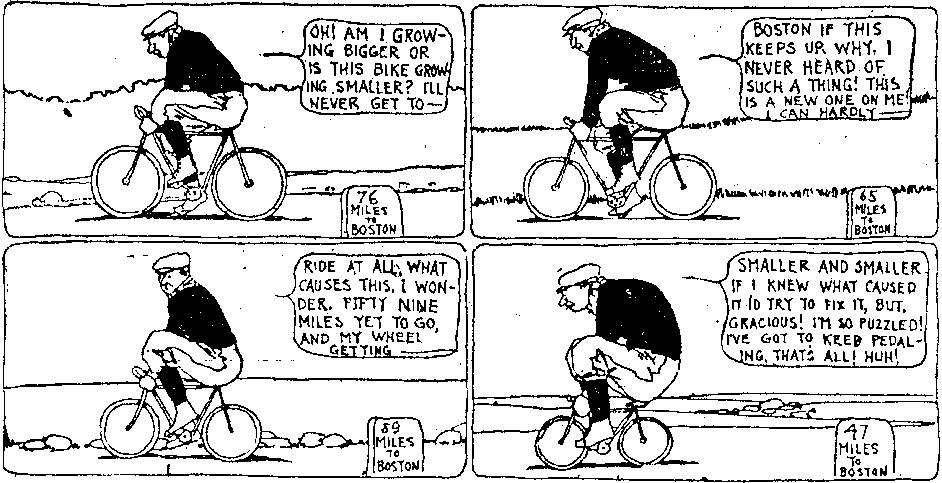

The earliest dreams I can remember were of diving from unspeakably beautiful gold cliffs and bouncing off the ground. I also had a nightmare that came back a few times: a distant figure on a bicycle was riding toward me from the flat, featureless horizon. He was just a speck at first, but as he approached I could see that he was riding as fast as he could in my direction, hunched forward, wrapped in a thick hunting coat with many stuffed pockets, full of malign intent. As he rode, his bicycle wobbled evilly from time to time, like a toy gyroscope just before it falls, and then he would regain control. I was very frightened by the wobbling. For years in grade school I used the memory of that dream to help me stop laughing—I had a problem then with fits of uncontrollable suppressed laughter.

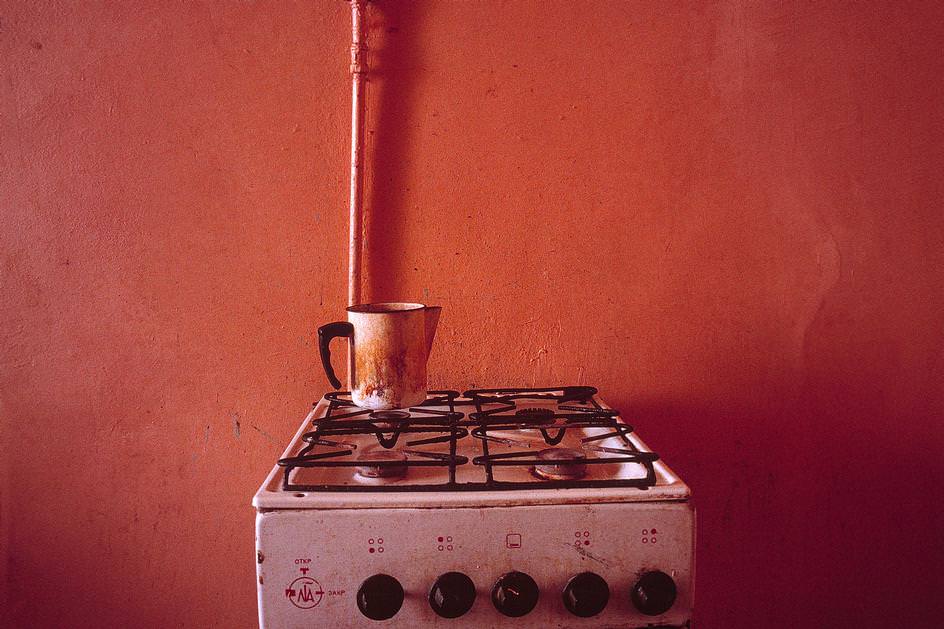

You can’t fight it. It happens. The dreams come on. They’re part of what we do. I had a theory once, which I also put in a novel, that many nightmares were caused by a common physical need: the need to get up in the middle of the night and go to the bathroom. Out of the stochastic stew that sits cooling on the stovetop of our sleep-softened consciousness, a couple of images would be ladled out in a bowl and sprinkled with a special neural Pickapeppa Sauce that made them seem frightening, so as to wake us up. All our subconscious was trying to do, I thought, was to help us by saying, Friend, your bladder is overfull and you should get up and relieve it. The only way that it knew to wake us up was by making our hearts race and filling our minds with fear. I still think that this model can explain many, though by no means all, nightmares.

The worst dreams I have these days are ones in which I have to go on stage and give a talk in front of an audience of smart attentive people, and I’m unprepared. I’m supposed to be full of wisdom on some specialized topic—say Voltaire’s voluminous correspondence with Stanislaw Lem—and my brain races to remember what I have to say on this subject, which is nothing. Why have they asked me here? I try to remember a joke or a witty phrase with which to begin my talk, and no phrases come. The stage manager says that it’s time. I hold up a finger and excuse myself and search around frantically in a pouch in my briefcase for a tiny bottle of magical alcohol that will help me relax and remember and give me a bluffer’s courage, but the bottles in my briefcase are all empty. Then suddenly I’m at the podium, with the microphone staring me in the face like the creature that pops out of the man’s stomach in Alien, and I realize that I’m dead sober and the evening isn’t going to be a success. In the shadows of the auditorium I see the intelligent face of a listener in one of the front rows fall in disappointment. Awful.

Advertisement

When, after I wake up, a bad dream that I’ve just had is dissolving slowly but is still present and worryingly believable, I sometimes rewrite it to give it a happy ending. It’s good to be able to save my family from some threat—the huge wave that towers high over the swimming pool, for instance. My infant son and I were going to be swallowed up in the terrible emerald-green cresting wave, but thanks to my newly aware and wakeful ability to make quick decisions, I can pluck him from the swimming pool and haul him quickly to a place of safety behind an immovable concrete pillar—no, not the pillar, we’ll drown. We grab a nearby floaty, my son and I, and cling to it, and ride out the wave, and my wife and daughter are safe too, it turns out. They were at Cumberland Farms the whole time, buying cat food. What a relief.

Part of a continuing NYRblog series on dreams. Previous posts include Georges Perec’s “Fifty Kilos of Quality Meat,” Charles Simic’s “Dreams I’ve Had (and Some I Haven’t),” and Michael Chabon’s “Why I Hate Dreams.”