This is one in a series of reminiscences by staff members of The New York Review of Books about their time working at the magazine.

It was 1975, and I was waiting in an office at The Village Voice to talk to Alexander Cockburn about ideas for editorial jobs at papers or magazines. Alexandra Anderson passed by and, realizing it had slipped his mind, took over, quickly conjuring up a list that included her friend Whitney Ellsworth, publisher of The New York Review of Books. It turned out there was an opening there as an assistant to Robert Silvers.

The Review was in a colorless block at 250 West 57th street, in the Fisk Building, a 1921 Carrère and Hastings brick structure whose lobby smelled of the Chinese food from the Yangtze River Restaurant that opened onto it. Lincoln Kirstein got mugged in the elevator there after delivering a piece to us. The Review, on the fourteenth floor, was a maze of small rooms, with little light, dark wood furniture, books, galleys, manuscripts, and cockroaches everywhere, reminiscent of the broom closet look of editorial offices at that time in Paris. Bob had two assistants who sat in his office with him; I was replacing Deborah Eisenberg. One of the first, most daunting things I had to do was sit at the front desk—perhaps there was a headset, or was it just quieter?—and on the phone take down a piece from V.S. Naipaul, who was in Zaire. How many times can you politely say “What?” and “So sorry”? But somehow the task got done. We were not in that space for long, though long enough for Bob’s other assistants Annalyn Swan to depart for Time and Daphne Merkin to leave to pursue her own writing.

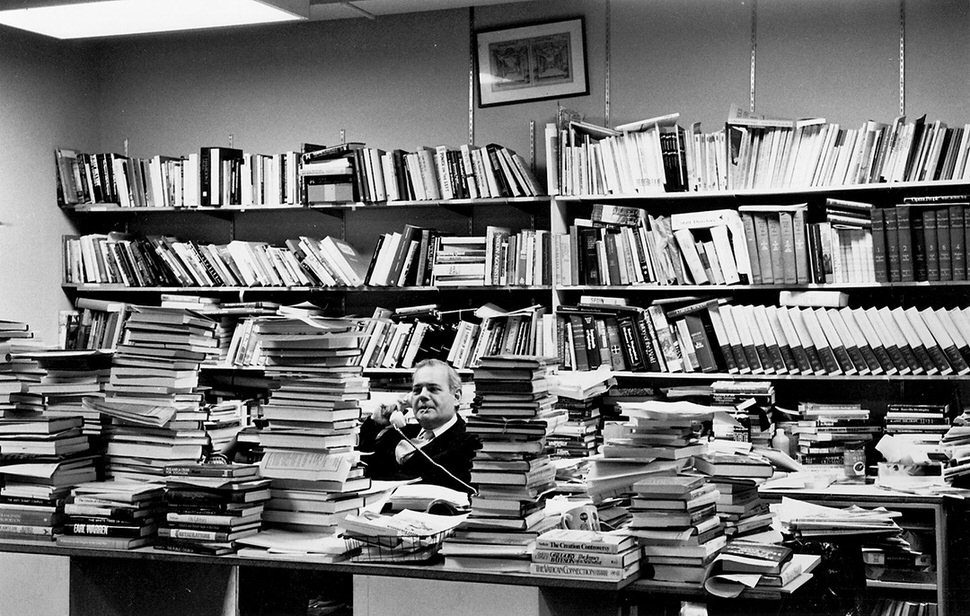

In the new, spacious, light-filled rooms on the thirteenth floor—Suite 1321—there was the addition of some industrial carpeting in the main offices, which nonetheless retained a comforting air of disheveled, bohemian mess. Bob’s habit of chain-smoking long, thin, dark brown Nat Sherman cigarettes created a thick cloud of smoke that made his office look like a bad day in Beijing, only compounded by the occasional fire that started in the large, boxlike brass floor ashtray with lions’ feet to the left of his desk and the smoke from just outside where Luc Sante, one of Barbara’s assistants, sat and exquisitely rolled and smoked his own cigarettes.

In the morning, it was usually rather quiet until Bob dashed in—a tornado of energy—around 10 or 10:30, having already been up at dawn calling Europe from home or pulling an all-nighter on some review not in good shape. He, of course, had a thousand ideas and out of his suit pockets fished a matchbook cover or some other scrap with the crucial contact, writer’s name, or the title of a book—little leads from the day before at the Council on Foreign Relations or maybe a dinner party that night—which we were meant to pursue immediately. “Immediately” being the favored mode of operation—how else could he get that story, or that writer? This involved a lot of phone calls and then whatever letter with a bound galley did not go by express mail left the office with Christopher Burke, our in-house messenger, who flew around the city delivering and picking up packages often until nine o’clock.

Many nights Bob came tearing back into the office at 11 pm after a dinner. One of his three assistants I worked with—Shay Cunliffe, then Tamar Jacoby, Mark Danner, and later Pat Storace—would be there: two of us did the 10 to 6 shift and one the 2:30 to 9, which could drift to later. Sharon Delano, an assistant editor, was often there reading copy or, when we were about to go to press on Thursday evening, reading the boards with Barbara Probst.

In the evening, if Bob did not go to dinner or the opera, around 8:30 he might go for some quick laps at the Henry Hudson Hotel nearby on 57th street, return to have a dinner of soup delivered from Carnegie Deli, and settle in, sometimes until after midnight. Who could match his stamina. I only managed a few four hours until after-midnight dictation sessions when Bob and Noam Chomsky were arguing, and firing back and forth extremely long letters about Cambodia.

I was, however, on the late shift with Bob around 9:30 on the steamy July 13 night when the lights flickered and everything went dark during the 1977 blackout. Bob, always optimistic, was convinced the lights were coming back on, and they did flicker a few times more, and so we sat at our desks like two sentinels and made small talk about some people in New York. At one point Bob had the idea that there might be something as practical as a flashlight in the office, so we both set off rather cautiously in different directions to look, around business manager Ray Shapiro’s office and the mailroom. That proved futile and we returned to Bob’s office to wait it out a bit longer. Finally after about forty-five minutes more we gave up and walked down the thirteen flights with the other tenants and out onto 57th street where there was general panic and a bit of chaos. Somehow we found a cab and I dropped Bob at 62nd and Madison and headed further uptown.

Advertisement

In the daily routine, it took three of us—always sitting in Bob’s office—to handle procuring the publishers’ catalogs, ordering the galleys, searching out the accompanying articles or bound books that provided background for a given review, typing up the letters attached to the piles of galleys, sending telexes on the little machine in front of the window that looked south toward downtown, and making the many necessary calls—Get me Isaiah (Berlin), Let’s call Vidia (Naipaul). It also took three of us to forget that Bob needed a visa for Japan, where upon landing he was detained by the authorities until the Japan Society rescued him.

Bob’s great curiosity, his phenomenal powers of concentration, his ability to work up a difficult subject in no time, to clarify language and totally rewrite a review if it was a piece he cared deeply about is known, but to observe it was daunting, not to mention his routine of devouring all printed matter—there was hardly a paper or literary journal we did not get. The brilliant and original matching of writer to subject with the expectation of an important in-depth discussion—often more interesting than the book being written about—still puts the Review in a league of its own and as Scott Sherman has written in The Nation, the Review has also always published political pieces that “took up the slack and presented viewpoints which were extremely hard to get into the established media.” In those years who else would have published on a regular basis Stuart Hampshire, Tony Quinton, Noel Annan, V.S. Pritchett, John Richardson, Richard Wollheim, Stuart Hampshire, Joan Didion, I.F. Stone, Kenneth Clark, Sybille Bedford, Hannah Arendt, Jean Starobinski, and Nadine Gordimer among many others?

In the controlled chaos of an ordinary day, there was a sense that anyone and everyone might walk through the door and they did. A very young Bernard Henri-Levy, even then with an unbuttoned shirt and a beautiful girlfriend in a peasant skirt, Emma Rothschild, Joseph Brodsky, Bob Hughes, William Shawcross and Marina Warner, Frankie Fitzgerald, Jonathan Miller (we ordered his button-down Oxford shirts from Brooks Brothers), Susan Sontag; Renata Adler came by for a quick lunch at Patsy’s, the Mob restaurant around the corner; Oliver Sacks, Ronald Dworkin, or Sidney Morgenbesser might just appear on their way somewhere to drop into the big leather chair to the right of Bob’s desk to chat as we all became attentive eavesdroppers. Jonathan Lieberson would come by to work on a philosophy review; advisory editor Lizzie Hardwick, in a colorful knit Missoni suit, would stop in to chat with Bob, ever charming, always smiling as she delivered her biting, incisive insights in that melodious southern accent before going to a meeting in Whitney’s office with Bob, Barbara, and Jason.

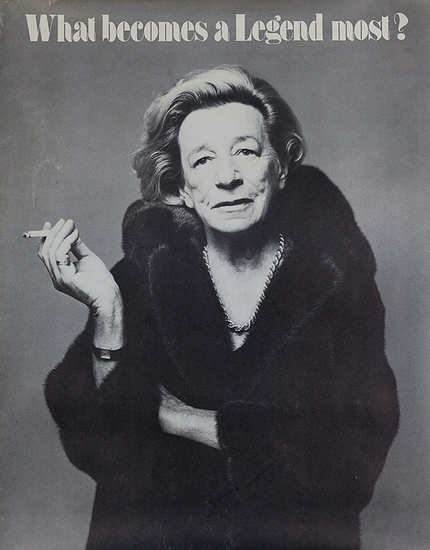

When the office did reach study hall quiet sometimes in the afternoons, it was Barbara’s distinctive laughter talking to one of her writers—Karl Miller, Murray Kempton, Alison Lurie, Gore Vidal, or Diane Johnson—that broke the silence. Or it was a shriek from the typesetting studio where Prudence Crowther was in a state of disbelief about the tenth set of changes from Charles Rosen, in total contrast to a review by Stanley Hoffmann, who would turn in an elegantly handwritten first draft that went to press nearly untouched. Prudence, known for her wry sense of humor, had created a fantastic, rather satirical collage of ads and photographs, a work in progress on the studio door, including that Blackgama ad “What becomes a Legend most?” with Lillian Hellman posing in a mink.

Whitney brought in his hunting dogs on certain days and the small mailroom got particularly crowded because in addition to Mack and Michael Johnson, who worked there, the literary agent Luis Sanjurjo used it as an office, stopping by with several long sheets of lined paper listing the forty people he needed to call every day. And Jones Harris, the son of Ruth Gordon and Jed Harris, either called or made spontaneous visits to tell Bob his latest conspiracy theory about the Kennedy assassinations.

Advertisement

It was my favorite publication when I went there and it still is. I had to force myself to leave in 1982. Bob gave me a enthusiastic send-off: “Well Kiddo, you have to do what you have to do.” This is just to say many congratulations for putting out the most important publication of our time, a great inspiration to us all: to Bob, Jason, and Rea, and a dedicated staff—and to the memory of Barbara—on your fiftieth anniversary.

Shelley Wanger is a senior editor at Pantheon and Knopf. She was an assistant to Robert Silvers from 1975 to 1982.