Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road,

Healthy, free, the world before me.

—Walt Whitman

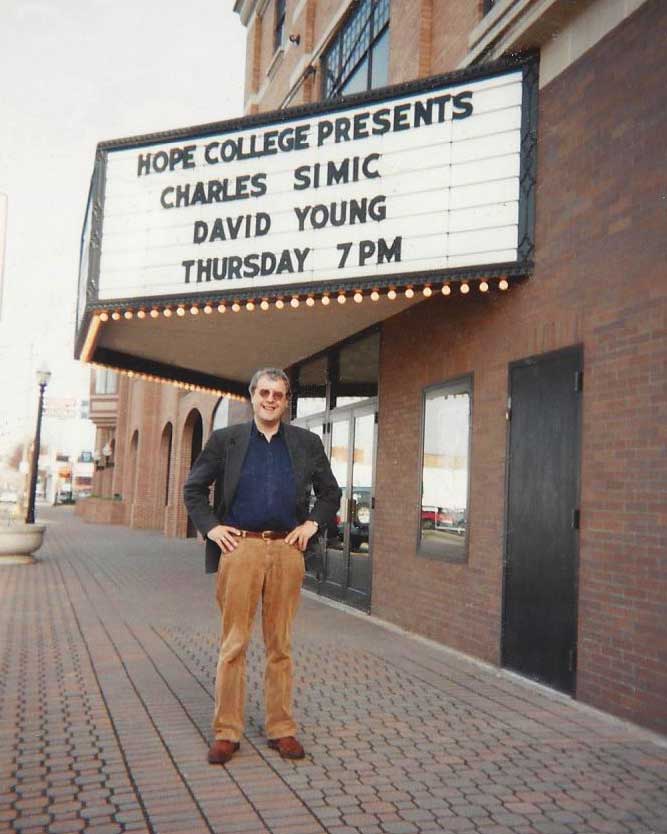

Like other poets of my generation, I’ve given hundreds of poetry readings. Over the last forty-five years, I’ve been to colleges and universities, but also to high schools, libraries, bookstores, grade schools, bars, nursing homes, jazz clubs, coffee houses, movie theaters, abandoned malls, and places that don’t fall into any of these categories, like that storefront where I shared the bill with a magician and a local rock band. It was packed, I remember, with a rough young crowd who were there to hear the band and who were okay with the magician being the first act, but grew unruly once they learned that a poet was to follow. If I didn’t panic and run, it was because I desperately needed the hundred bucks I was to be paid, and because I already had some experience with hostile audiences, being a veteran of New York City’s “poets in the schools” program, where I discovered that the kids the teacher warned me about as being the worst of the worst had greater aptitude for modern poetry than their supposedly better-behaved and academically superior classmates.

After my first book of poetry came out in 1967 and received some favorable reviews, I started getting calls and letters from schools around the country inviting me to come and read. If the money being offered was acceptable, I’d say yes. Depending on the distance, I traveled by plane, train, bus, or in my own car; I have now after all these years given readings in nearly every state of the continental United States. How else, I realize today, would I ever have gotten to see Pittsburg, Kansas; Brookings, South Dakota; Milledgeville, Georgia; Walla Walla, Washington, and many other such out-of-the-way places? To orient myself geographically upon arrival, I’d ask my hosts the name of the nearest big city. Their answers often disoriented me even more. Denver, someone once cheerfully informed me, was only 350 miles away.

Since I held a full-time job, these trips could not take longer than a day or two, which usually meant that I arrived in the afternoon and left the next morning. On a trip to Montreal, to give you an idea how it went, two professors from the university where I was to read picked me up at the airport, took me to drop my bag in the room reserved for me at the Ritz, and then to lunch in a lovely little bistro in an old French neighborhood where we lingered over our third bottle of wine till it was time for me to visit a class. Then I had an early dinner with some other faculty members, after which I gave my reading and attended a party in my honor at someone’s house which lasted into the wee hours of the night, so that I didn’t get back to my hotel till four in the morning. There was just enough time to shave, change my shirt, and check out before catching the first flight to New York—recalling with regret, as I sat dead tired on the plane, the splendor of the room I never slept in and the smell of fresh croissants being wheeled past me on a cart as I ran out of the hotel to hail a cab.

On most of these trips, of course, my accommodations were far from luxurious. I stayed in highway motels, student dormitories, children’s rooms in people’s homes, and creepy old mansions used as faculty clubs during the day, where I would be the lone guest for the night having to contend with their ghosts. In the 1970s, when states like Ohio, California, Oregon, and Connecticut still had what were then called “poetry circuits” in which a dozen or more colleges made a joint agreement to invite the same poet over a period of two weeks, one was given a rented car and a set of travel directions and took oneself from town to town in the state, giving a reading in early afternoon and another one at night, sleeping wherever one could, even in one’s own car when overcome with fatigue. Besides being exhausting, these tours were also exhilarating. Writing poetry is a solitary activity. Most of the time one has zero confidence in what one is doing. The poems, even when they are published in literary journals, are read by people one very rarely hears from. Public readings assure poets that there is an audience for poetry in this country and that Americans not only can make sense of their poems, but appear to actually like them.

It was also nice to have a car and be able to cut and run after the reading was over. Academics, by and large, don’t make the most entertaining dinner table company. Their preferred topic, even in the presence of a stranger, is the department in which they teach and its squabbles. It’s often more fun to hang out with graduate students, who are more likely to know where good live music can be heard. There are occasions, however, when there are other reasons to make a fast getaway. The shortest reading I ever gave in my life, even though I was specifically told that they expected a full hour from me, was due to factors which, as far as I was concerned, were beyond my control. It was the night of an important NBA playoff game between the Knicks and the Celtics, and I made the calculation that I had to be back in my motel room exactly thirty minutes after watching the end of the first quarter to be in time to see the fourth, and was, leaving my hosts and my audience visibly shocked.

Advertisement

Among many memorable adventures on the road, this next one may be the strangest of them all. I was invited to read at San Jose State, but before the reading there was a dinner at a private home in a nearby town. My hosts, as I discovered to my delight, were a high-spirited bunch, the food and the wine were excellent—when suddenly one of them shouted that we were going to be late for the reading, and the whole dinner party leapt to their feet, rushed out of the house leaving the food on the table, and piled into two cars, telling me to follow them in my own. I did that until we found ourselves in a heavy traffic on a highway heading for San Jose. Before long, I lost sight of them, but drove on unperturbed thinking they’d realize I wasn’t behind them and were sure to stop in the breakdown lane and wait for me, since all I knew about the reading I was going to give is that it was not at the college, but in some church downtown. To my annoyance, I drove past all the downtown exits and several southern suburbs with no sign of them. Finally, finding myself in the open country, I said to hell with it and decided to head for San Francisco. Since, in order to get there, I had to go back the way I came, I decided on the spur of the moment to take one of the downtown exits and ask someone if they knew anything about the reading, except there was no one to ask past eight o’clock in the evening in a dark neighborhood of small apartment houses and tree-lined streets. After circling for a while I saw an old Chinese man walking slowly by himself. I pulled over and called out to him, while being very conscious how ludicrous I sounded, did he by any chance know of a church where there was to be a poetry reading tonight? Yes, he said, right around the next corner.

Charles Simic’s New and Selected Poems: 1962–2012 has just been published. His poem “As You Come Over the Hill” appears in the New York Review’s May 9 issue.