The closer you look at an octopus, the more you see.

Consider its anatomy: the “head,” a sack resembling a human scrotum that can shift through the entire color spectrum; the three hearts pumping blood that contains copper rather than iron; the eyes so very like human ones and yet radically more elegant in design. In a celebrated poem Ogden Nash begs the octopus to tell him if its limbs are arms or legs. Textbooks have a no-nonsense answer: they are arms, not legs (and emphatically not tentacles). But super tongues would be at least as good. Each octopus arm is a muscular hydrostat, like a human tongue, and each of the tens or hundreds of suckers on it is lined with tens of thousands of chemoreceptors—taste buds to you and me—and a comparable number of nerve endings that provide an exquisite sense of touch.

Or consider its intelligence: In experiments carried out with the Common octopuses, individuals are faced with five opaque doors, only one of which has a crab, which they love to eat, hidden behind it. Different symbols are visible on each door. After a few tries, the octopus accidentally chooses the correct symbol. In subsequent trials, the octopus quickly recognizes the symbol and opens the correct door, even when they are all moved around. If a crab is placed behind a door with a different symbol the octopus quickly learns the new symbol. In other experiments octopuses have shown ability to distinguish symbols about as well as a three- or four-year-old child.

Octopuses also play—there is no other word—with objects that are of no apparent use to them, such as little balls thrown into their tanks. These behaviors, and others, are unique among animals without back-bones, and more sophisticated than any displayed by fish as well as many reptiles and mammals.

Their intelligence is all the more striking because it has evolved completely independently of the line that gave rise to us: our last common ancestor—perhaps some simple, slug-like creature—lived well over 540 million year ago. Humans are more closely related to starfish and sea cucumbers. And yet across a chasm in evolutionary time we encounter a creature with some striking resemblances to ourselves: a mind that calculates and even, perhaps, possesses a form of awareness. In some ways, their abilities surpass ours.

There are more than three hundred different octopods (that is, species of octopus). One species, the blanket octopus, has the most extreme divergence in size between the two sexes in a single species of any animal: females weigh 10,000 times as much as males. Having sex must take imagination, as well as skill. Stauroteuthis, which lives in open water 2,000 meters below the surface, glows in the dark to attract prey, and inflates its webbed pink arms to make what is probably the world’s only bathypelagic tutu. The deepest living octopus discovered so far—typically 3,000–4,000 meters down—is Grimpoteuthis, popularly known as the dumbo octopus because large flaps on its body resemble the ears with which the cartoon elephant flies.

The Vampire squid—which is actually an octopodiform and not a squid, and looks like an apparition from an impossibly ancient dream—is harmless to humans. But the tiny blue ring octopus, which lives in shallow waters around Australia, is one of the most venomous animals in the world despite being only a few inches across. The mimic octopus, which was only discovered in 2005 in shallow Indonesian waters, can rapidly morph its body to resemble a flounder, a sea snake, a lionfish, and almost anything else it sees. Its cousin Wunderpus photogenicus, discovered in 2006, is not so flexible but the contrast between its white stripes and the rich red-brown background of its body is nature’s answer to the op art of Bridget Riley.

Compared to this reality, our cultural imagination is massively impoverished. Octopuses are more likely to appear as an item on the menu, as a scary monster in a creaky horror movie, as a participant in Japanese soft porn, or as an item of World Cup infotainment. Appetite, loathing, and lust have certainly played big parts in human imaginings of these beasts. But we should take a cue from the Minoans who portrayed them in images that, even after 3,500 years, almost sing out loud in celebration of their strangeness and beauty.

After the Minoans the octopus seems to have only played a bit part in the ancient Mediterranean imagination. Homer compares Odysseus to one, but only when he is at his most vulnerable, about to be dashed to pieces on a rocky shore. Large varieties of giant squid were known in the ancient world—Aristotle records specimens up to five ells, or about two and half meters long, and much larger ones exist far out to sea. But even if Scylla is partly inspired by sightings of these, it is also a chimerical monster, knotted together in the depths of the human mind from many forms. The same goes for Lotan, a seven-headed sea monster of Phoenician myth.

Advertisement

The nearest we come in the ancient world to something claiming to be a factual account of a monstrous octopus is in Pliny’s Natural History, written about AD 77:

for if [this animal] chaunce to light upon any of these dyvers under the water, or any that have suffered shipwracke and are cast away, hee assailes them in this manner: He catcheth fast hold of them with his clawes or armes, as if he would wrestle with them, and with the hollow concavities and nookes betweene, keepeth a sucking of them; and so long he sucketh and soketh their bloud (as it were cupping-glasses set to their bodies in divers places) that in the end he draweth them drie.

Pliny continues with the story from a place called Carteia of an octopus that used to come in from the open sea to raid uncovered tanks on a fish farm and forage for salted fish. Frustrated by the continual theft, human overseers put up fences to keep it out, but the octopus learned to climb over them by means of the overhanging branch of a tree. At last it was cornered and fierce dogs were set on it but the animal almost got the better of them, and it was only finally dispatched by several men armed with tridents. The animal’s arms were almost thirty feet long, says Pliny. Its carcass weighed nearly 320 kg (700 lb).

This begins to sound like urban legend, the Roman equivalent of rumors of alligators in the New York sewers. There could, however, be some truth in it, at least regarding behavior if not size. Octopuses can be determined hunters and they often make short journeys across land between tide pools in search of food. Some can go for twenty or thirty minutes out of water so long as their gills are wet, and there are several well-documented accounts in recent years of individuals escaping from tanks in aquaria and laboratories, climbing up and down furniture and slipping into other tanks some distance away to eat their inhabitants. (In some cases it took a hidden camera to catch an octopus squeezing through unbelievably small spaces and back again.) There are credible stories, too, of octopuses climbing on board fishing boats at sea and stealing crabs out of the hold.

It is not until about fifteen hundred years after Pliny that another European tries to describe the octopus dispassionately. Around 1595 the Italian naturalist and polymath Ulisse Aldrovandi compiled all the information he could find as part of his monumental encyclopedia and “theater” of natural history. Octopuses live, Aldrovandi declared, on land as well as at sea, moving with as much ease over rocky ground as they swim underwater. They are stronger than the eagle and fiercer than the lion. They are voracious eaters and, when not chasing fish and crustaceans, are partial to fruit (especially figs), olive oil, the odd human, and even their own arms. They can turn every color except white. Eaten without garnish they are an aphrodisiac; cooked in wine, an abortifacient.

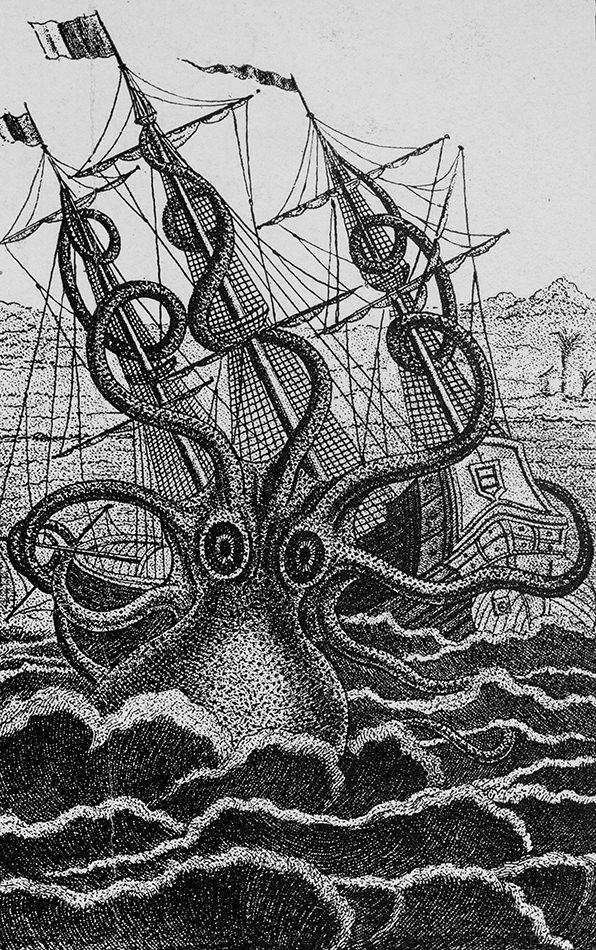

But even as Aldrovandi was writing, stories circulated in Europe of a huge and terrifying beast that would have more impact on popular ideas of the octopus than any number of scientific studies. In northern Europe great water beasts date back at least as far as the Norse sagas, in which Thor battles a giant sea serpent called Jormungander. Other stories tell of eight-legged monsters known as the Kraken, a name derived from krake, a Scandinavian word for an unhealthy animal or something twisted. (“Crooked” in English comes from the same root, as does the modern German name for octopus, der Krake.)

Linnaeus thought the Kraken sufficiently credible to include it in the 1735 edition of his Systema Naturae (although he dropped it in later editions).

Linnaeus was not completely deluded. Giant squid such as Architeuthis (ten meters long) and Mesonychoteuthis (fourteen meters) do exist—a fact that biologists only finally accepted in 1857. But they are extremely elusive: even today only a very few have been caught, and a great number of very strange species still lurk on the threshold of human knowledge. It’s easy to see how, when briefly glimpsed in earlier times, a living one—or of its boneless, twisted remains—could have been mistaken for a giant version of the more familiar octopus.

Because they were so elusive, giant cephalopods were excellent fodder for fabulists. In the early 1800s the French malacologist Pierre Denys de Montfort published an account of a British ship of the line that he claimed had been sunk, and its crew devoured, by a colossal octopus, or Kraken. De Montfort was ruined when his fraud was exposed, but the images he created endured, inspiring among other things a sonnet by the young Alfred Tennyson in 1830 and a fountain of schlock horror monsters ever since.

Advertisement

In Victor Hugo’s 1866 blockbuster, Toilers of the Sea, the hero is caught in the grip of a giant octopus. The creature is “the very enigma of evil, a viscosity with a will, a boneless, bloodless, fleshless creature with one orifice serving as both mouth and anus, a medusa served by eight snakes, coming as if from a world other than our own.” Hugo seems to have read his Pliny, but he pulls out all the stops in wild exaggeration and extreme anatomical confusion:

It is a pneumatic machine that attacks you. You are dealing with a footed void. Neither claw thrusts nor tooth bites, but an unspeakable scarification. A bite is formidable, but less so than such suction. The claw is nothing compared to the sucker. The claw, that’s the beast that enters your flesh; the sucker, that’s you yourself who enters into the beast. Your muscles swell, your fibers twist, your skin bursts beneath this unworldly force, your blood spurts and frightfully mixes with the mollusk’s lymph. The beast is superimposed upon you by its thousand vile mouths….

Paul, a common octopus, shot to global fame after appearing to predict the winners in a series of matches up to and including the final of the 2010 Football World Cup. (He was offered a choice between two boxes both containing a mussel as a snack, each box marked with the flag of the country of one of the two opposing teams in an upcoming match. He consistently went to the box with the flag of the team that went on to win.) It was a story that everybody loved. At one point Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero of Spain offered to take Paul under state protection, while the Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad identified him as conclusive proof of the decadence of the West.

Paul’s “predictions” can, of course, be explained by chance, bias, and other factors. But what this episode shows—apart from the rather unsurprising fact that German zoologists have a better sense of humor than conservative Iranian politicians—is that it is possible for an octopus to capture the popular imagination without being a monster. Having got this far, perhaps there is a chance that more people can learn to see ordinary octopuses as remarkable creatures without the packaging of clairvoyance and football.

The computer scientist, musician, and virtual reality pioneer Jaron Lanier is a big fan of cephalopods. “[They] taunt us with clues about the potential future of our species…. [Their] raw brain power seems to have more potential than the mammalian brain…. By all rights, [they] should be running the show and we should be their pets.” The reason that this is not the case—as Lanier and others point out-—is that almost all cephalopods are very short-lived. The Common octopus typically lives less than a year and even the largest species only live three to five years—and die before their young are born. As a consequence, they do not get a chance to pass on what they learn to the next generation. Cephalopods have no culture: no childhood in which they are guided by their parents. They must start from scratch in every new generation.

Still, argues Lanier, we have a lot to learn from the octopus. Its impressive ability to communicate complex meanings by altering the color and texture of its skin—to literally embody meaning—could be an inspiration for what humans may one day achieve in the realms of “post-[linguistic] communication,” which would give rise to a “vivid expansion of meaning.” Lanier was anticipated by Michel de Montaigne, who noted in 1567 that “the octopus assumes whatever color it likes to suit the occasion, hiding, say, from something fearful or lurking for its prey.” Taking this as an example of how other animals sometimes far surpass us in certain abilities, Montaigne suggested: “We have fashioned a truth by questioning our five senses working together; but perhaps we need to harmonize the contributions of eight or ten senses if we are ever to know, with certainty, what Truth is in essence.”

Excerpted and adapted from The Book of Barely Imagined Beings: A 21st Century Bestiary by Caspar Henderson, published this month by the University of Chicago Press.