Sipping gin-and-tonic sundowners on the terrace of Lunuganga, the Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa’s sprawling country house, he and his principal collaborator during the 1950s and 1960s, the Danish architect Ulrik Plesner, now eighty-two, might impulsively decide to extend the parapet beneath them by a few feet, or to render a distant vista more agreeable by removing hundreds of intervening trees. Within hours these changes would come to pass, thanks to an endless supply of cheap semi-skilled labor and a strong local crafts heritage.

There was no need for computers, let alone detailed working drawings. First-rate execution and installation of affordable custom-designed tiles, metalwork, and wood joinery could be taken for granted. Stone walls—quarried nearby and set without foundations (which would only have complicated inevitable future changes)—were laid out with strings stretched between stakes. The only impediment was playful monkeys who might disrupt those temporary outlines overnight.

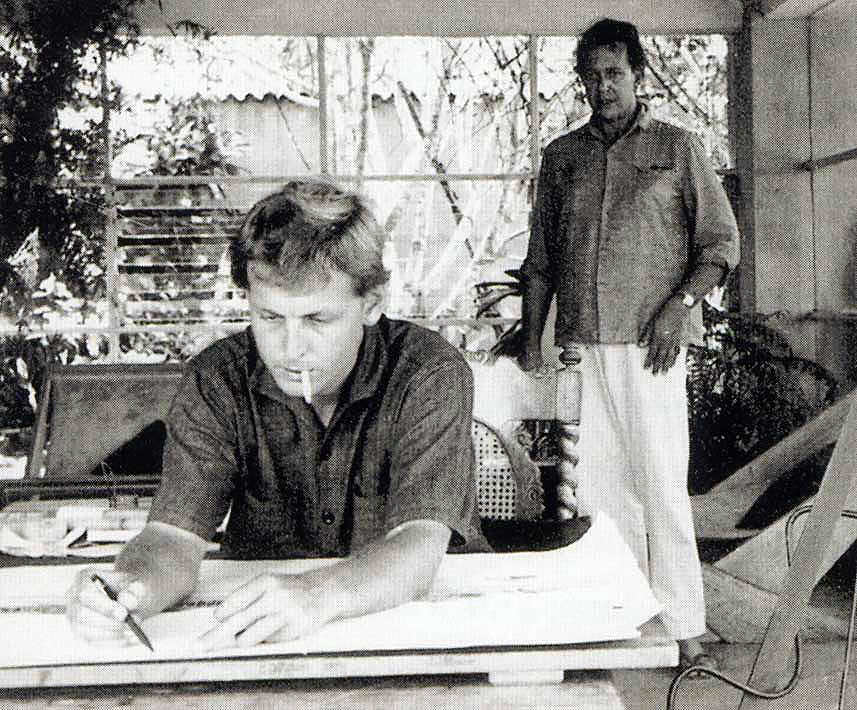

From 1958 to 1966 Plesner was the chief architectural partner of Bawa (1919–2003), the master builder of mixed Sri Lankan Muslim and European ancestry who has become a cult figure to those who believe that the lessons of the Modern Movement should be more sensitively adapted to indigenous cultural traditions. Along with his own estate and a large number of other private houses, Bawa designed some fifteen hotels throughout Southeast Asia that were hugely influential in showing how tropical resort architecture could move away from generic Hiltonism without recourse to kitschy folklorism.

Although he has often been called the Luis Barragán of the Eastern Hemisphere, Bawa’s works were built far beyond the geographic purview of Eurocentric scholarship, and his masterpiece, the majestic Sri Lankan Parliament Building of 1979–1982 in Kottke (designed after Plesner’s departure), remains little known in the West. This serene cluster of wood-sided pavilions with deeply overhanging roofs is set on an artificial lake and approached across a causeway, which gives the complex an exalted feeling akin to a temple precinct (though the assembly chamber’s interior was loosely inspired by the British House of Commons).

Plesner’s absorbing new account, In Situ: An Architectural Memoir from Sri Lanka, depicts Bawa’s Ceylon—which won independence from Britain in 1948 and changed its name to Sri Lanka (Sanskrit for “resplendent island”) in 1972—as a prelapsarian architectural paradise where one barely had to think about creating something before it materialized into being. When Bawa and Plesner began their collaboration, however, the influence of Le Corbusier’s International Style was pervasive in the developing world and the inherent advantages of regional building methods were not immediately obvious.

Among Le Corbusier’s cardinal tenets, for example, was the flat roof, which caused progressive architects everywhere to regard the pitched roof as artistic anathema—even in rain-soaked regions like Sri Lanka, where for ages it had been the most logical form of shelter. The inadequacy of the Corbusian approach was among the invaluable lessons Plesner learned from his extensive on-site studies of the island’s ancient architectural treasures, which spurred a historic preservation movement there.

Bawa and Plesner were not immune to the flat-roof fad, as this richly illustrated volume demonstrates. But, Plesner writes, they eventually embraced the overriding good sense of time-tested responses to building in a tropical climate:

With the discovery of the universal Big Roof, things fell into place.….Openness under big roofs became the key to beauty, comfort, economy, ecology, and pleasure, as in fact it still is.

As with other, better known architectural collaborations, the division of labor between the celebrated Bawa and the relatively obscure Plesner remains somewhat elusive, and the who-did-what question loomed large as I read In Situ. The Cambridge-educated Bawa, who became an architect at age thirty-eight after a first career as a barrister, possessed a superb eye and faultless taste, but scant practical know-how.

The more technically adept Plesner came to Sri Lanka in 1958 and on the recommendation of a mutual friend began working with Bawa, who just the year before had qualified as an architect after studying at London’s experimentally oriented Architectural Association, where he made a name for himself among his much younger contemporaries by rarely attending classes. Plesner’s influence was especially evident in the high modernist finesse of their Ekala Industrial Estate of 1960-1965 in Ja-ela, a bold concrete composition that would fit in well with Don Judd’s later Minimalist sculptural installations in Marfa, Texas.

To his credit, Plesner does not emphasize his own importance at the expense of his partner’s, as did the structural engineer August Kommendant in his self-aggrandizing if hugely informative memoir 18 Years with Architect Louis I. Kahn (1975). Instead, he generously stresses the complementary nature of his and Bawa’s respective talents:

Advertisement

Never any explanations or arguments or theories. The communication was almost musical; modulations of hums, puzzled looks, crooked smiles.…What one lacked, the other had, as if we had emptied the contents of our pockets on the table and found that together we had a complete set of tools.

The author understandably looks back on the years with Bawa as a period of veritable enchantment, and conveys his experiences with the enigmatic master through dreamlike vignettes, like his site visits with Bawa—two pukka sahibs in his partner’s massive 1936 Rolls-Royce cabriolet, which attracted attention wherever they stopped:

….[A] crowd of children and villagers pressed around with smiles and sounds of admiration, choreographed like a ballet scene. They touched the car with feeling, and within a minute Geoffrey, centre stage, speaking in the most vulgar Singhalese, had the whole crowd giggling with delight….[and] surprise at a man, whom they thought was a European, but who spoke like a villager.

Once their partnership began to draw international attention, however, the principals’ laid-back attitude toward attribution frayed as one partner got more credit or press coverage than the other. And when the Sri Lankan government moved into the Communist Chinese sphere of influence during the Vietnam War, Plesner felt that his time in this increasingly menacing erstwhile Eden was drawing to a close.

After he left Sri Lanka, Plesner went on to a productive subsequent career—first in Britain for the giant architectural engineering firm Arup, then during the past four decades in Israel, where he served as city architect of Jerusalem (and where his son Yohanan Plesner has served in the Knesset for the centrist Kadima party). Yet these reminiscences make clear that he never again enjoyed anything like the magic of working with Bawa. In its finest passages, Plesner’s evocative testament reminds us that even though works of architecture may seem to be among the most durable human artifacts, nothing outdoes memory in its ability to reconstruct the past.

Ulrik Plesner’s In Situ: An Architectural Memoir from Sri Lanka, is published by Aristo in Copenhagen, Denmark.