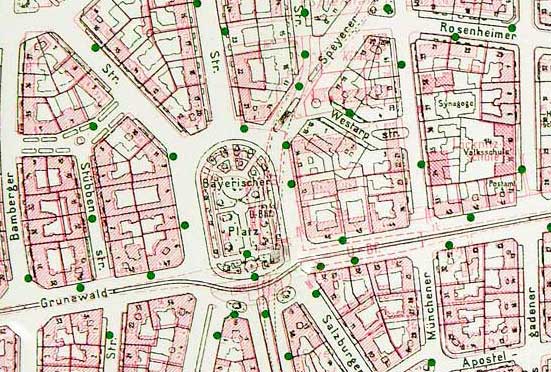

Twenty years ago this month, Berlin-based artists Renata Stih and Frieder Schnock inaugurated their hugely controversial “Places of Remembrance” memorial for a former Jewish district of West Berlin known as the Bavarian Quarter. At the time, Germany had just been reunified, and it was one of the first major efforts to give permanent recognition to the ways the Holocaust reached into daily life in the German capital. The 1991 competition called for a central memorial on the square, but Stih and Schnock instead proposed attaching eighty signs hung on lamp posts throughout the Bavarian Quarter, each one spelling out one of the hundreds of Nazi laws and rules that gradually dehumanized Berlin’s Jewish population.

Today, Germany is filled with memorials and institutions dealing with aspects of the Holocaust, including Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum and Berlin’s central Holocaust memorial. But Stih and Schnock’s in-your-face signs about Nazi policies, integrated into the present-day life of a residential Berlin neighborhood, remain one of the most visceral and unsettling. I recently walked through the Bavarian Quarter—which is part of Berlin’s Schöneberg district—with the artists to discuss their work and its legacy.

Ian Johnson: We’re standing in Schöneberg, which is probably best know to foreigners as the place where John F. Kennedy gave his “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech. But it’s also where the Nazis rounded up the city’s Jews. Your memorial went up at a moment when the country was just beginning to publicly commemorate the Holocaust. Now, there are many memorials, and a lot of those debates have played out. What has changed?

Renata Stih: I took my students around the Bavarian Quarter last week. They were so disconnected—“Oh we know about this.” As the last victims die off—and this is just a question of the next few years—we have to think about how we’ll educate the younger generation.

At the time you proposed the memorial, few people wanted to talk about what happened here.

Renata Stih: We started out by interviewing people with a hidden recorder. We asked people, “Do you know who lived here?” We got totally different reactions. One woman burst out in tears and she said, “Yes, I saw how they deported them.” No one wanted to say the word “Jew.” Another woman said, “Well, I think this was a Jewish area.”

The overall idea was to show this crime with double-sided signs. We didn’t want to show it from the point of view of victims but from perpetrators. We took anti-Jewish laws and regulations. On one side we had text, which we took from the regulations but made it snappy and shorter, so people driving or biking by could read them fast. And on the other side we put a picture that illustrated it. [One shows a chalice and on the other side of the sign says, “The baptism of Jews and their conversion to Christianity is unimportant in the question of race.” Another shows a radio and the other side says, “Jews must give up their radios.”]

But we absolutely avoided any kind of Jewish cliché—no Star of David, nothing. We didn’t want people to be able to say, “Oh yes, that was that.” So in rewriting the texts we used the present tense. But to put it back in time we used the date that it was passed at the end of the text.

And you put the word “Jew” in virtually every sign.

Renata Stih: Absolutely. Or “Jews and Poles.” In front of the delicatessen “Butter Lindner,” we put the sign that Jews and Poles are not allowed to buy sweets. We placed it there on purpose, so people would see it coming in and out of the store.

If you look across the street, there’s the Bayerischer Platz U-Bahn station with the subway sign—a white “U” on a blue background. Next to it is one of our signs with the same symbol. But on the back it says that Jews aren’t allowed to use the subway.

And a lot of this was centered right here, in the Bavarian Quarter. Wasn’t it a well-to-do district at the time?

Frieder Schnock: Yes, it had been an upper-middle class neighborhood.

Renata Stih: It’s really a nice area but I think this disturbed the Nazis the most: it was a center of intellectual life in Berlin. Albert Einstein lived here—we’re going to walk down to his house. And Gisèle Freund, the photographer, lived two houses down.

Advertisement

Frieder Schnock: And Carl Einstein, the art historian. Gertrud Kolmar the poet.

Renata Stih: And Hannah Arendt. They were all here. This was something disturbing.

The Nazis wanted to turn it into a Ghetto.

Frieder Schnock: They turned a lot of buildings into “Jew houses”—Judenhäuser—so you had more than 6,000 Jews who were here for deportation. They were put together in five-room apartments—five families in such an apartment, making life really miserable.

Renata Stih: They pulled people out at night. People told us that it happened mostly at night. Unfortunately there was no oral history. No one thought to interview locals in the 1970s and 1980s.

Over there you see a sign with a telephone—right next to the post office—and the sign says Jews aren’t allowed to use telephones. Everything was meant to exclude Jews from daily life, from social structures, and to threaten them.

The competition for the Schöneberg memorial was announced in the winter of 1991 and they had a lot of entries. Yours was among the final eight.

Renata Stih: During the process they asked the artists to present their work at a public forum. We showed little drawings, not the real size, which is fifty by seventy centimeters. The drawings were like fine watercolors. They gave the pictures a softness. This was very good because everybody focused on the art. Here, in real life, it looks like brash pop art, but at the presentation it was different. It was of course a trick. You have to be very careful when you present because otherwise you’ll scare people. You had politicians, you had the head of the Jewish community, the head of town planning. It wasn’t a normal committee for the arts.

Did people want something more traditional?

Renata Stih: The initial idea was to place a memorial on the square. That’s what they wanted. We changed it completely.

That was courageous of the jury to endorse your idea.

Renata Stih: I have to say that in 1993 the society was open—kind of not secured. It was right after the Wall had opened. I don’t think we could do it today. Today’s committees are much more conservative.

But even back then, it was controversial.

Renata Stih: There were all kinds of objections. Many people wanted names and we said we don’t work with names. We work with the social and legal structures: how could this ever have happened? This was our question. The laws were passed in a very refined way, starting in 1933 with laws that were already questioning every part of daily life. They were passed in special periodicals too, like for the bakers or pharmacists.

The first sign we attached to a lamppost was a cat. And on the other side it says, “Jews are not allowed to have pets.” The reason for that is that first the animals had to go and then the owners could be removed. Because if animals would stay in an apartment, they wouldn’t get food, they’d make noise, this would cause a commotion. Maybe the Aryan neighbors wouldn’t care about the Jewish neighbor being deported but they would truly care about a little cat meowing. People think this sign is cute, adorable.

Frieder Schnock: But Renata, the cat has another story too. When we were installing it, suddenly someone opened a window and yelled out: Haut ab, Judenschweine!—“Go away, Jewish pigs!” Our two workers installing the signs with us, they were completely shocked. They had thought the project wasn’t important until then and had been saying, “Come on, everyone knows this, why are you bothering?” They were speechless.

Now we’re on Haberland Strasse. It’s named after the developer Georg Haberland, right?

Renata Stih: When we started the project we found that this street wasn’t called Haberland Strasse but Treuchtlinger and Noerdlinger Strasse. The Nazis renamed all streets named after Jews. Georg Haberland was Jewish but he became a Protestant so he could be admitted to court, but he was considered by the Nazis to be Jewish. In East Berlin most streets had been given their original names back. Not in West Berlin. This says a lot about the political structures of West Berlin. When we started the project we said this can’t be; why haven’t you renamed the street back to Haberland Strasse? And actually nobody had ever thought of it.

So we made a sign that looks like a Berlin street sign that said this was Haberland street. And we put it in front of the building where he lived. After we put up the sign they had a long discussion about whether they should rename the streets. I find that ridiculous. Especially the Green Party said, “Oh, he’s an investor and investors are bad.” Without knowing anything about him, they said he was a bad guy and they said, “We can’t name it after an investor.” After five years they finally agreed to rename half the length of the street Haberland Strasse and one half stayed Treuchtlinger Strasse.

Advertisement

Frieder Schnock: The German solution.

Renata Stih: Up ahead is a nasty regulation. The regulation says Jews must give up all electrical devices, like radios or record players. On the reverse side we just showed a plug. You’re unplugged, you’re cut off from anything social.

You see this sign? It’s a pearl necklace.

Frieder Schnock: “Jewelry. Items made of gold, silver or platinum and pearls belonging to Jews are to be turned in to the state. February 21, 1939.”

Renata Stih: A friend lives here and said once to us: “Oh, I live next to the pearl necklace.”

Frieder Schnock: That’s what we wanted. We wanted kids to ask questions. They look at images and they’re going to ask questions. “Why is that image up there?” And adults have to come up with answers.

Renata Stih: Our memorial is uncomfortable. When the first ones were being put up, someone called the police and said, “There is anti-Semitic activity going on.” I saw a policeman writing things down. I went up to him and asked him what he was doing and he said, “I’m making notes because this will come down.” I said, “It can’t come down, it’s being inaugurated next week!”

But they took down the seventeen we had installed and arrested the two workers we had. On the spot we gave an interview on television and the commentary on the television was, “You see how they waste taxpayer money on anti-Semitism!”

Everyone turned against us. The political groups met over the weekend, then they had a crisis meeting and couldn’t decide. The senator who’d supported it was away, but eventually it ended in a good way. They approved it. But we had to add a small tag below each sign saying it’s a memorial.

Frieder, as we’ve been walking, you’ve been snapping pictures of the signs. Why?

Frieder Schnock: I check whether they’re intact. Sometimes a lorry drives up on the sidewalk and knocks it. Sometimes mildew grows on the signs.

This seems different from a typical project. It’s like you’re still curating it.

Renata Stih: Yes, friends help out too. They tell us if they see a damaged sign. Or this one—it has moss growing on the frame. In the future, signs might need to be reprinted and we want to have a place to store the material, and maybe a foundation to keep it up.

And soon you’re launching an app with translation in English, Hebrew and other languages. And you published a book about it in German and English. It must feel like a success?

Renata Stih: I wonder about the effect. Because if this is forgotten, there’s a possibility that it happens again. Not the same way and maybe not here, but there is a kind of disinterest about human rights as a whole. Because as long as people have a good life they think, “We’re a democracy and we have full employment.” There is a kind of superiority feeling toward other countries again.

But we want it to be uncomfortable. We don’t want people to say, “We didn’t know.”