A short time after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, a rumor ran through the southern Lebanese town of Saida that went something like this: as Israeli forces advanced into the country, one Israeli air force pilot refused to strike his assigned target, a secondary school for boys not far from the Ain El Helweh refugee camp. Instead, he veered off course, dropping his bombs into the Mediterranean Sea below. It was said that the pilot’s family had originally been from Saida’s old Jewish community, and he had felt too much of an attachment for the place and its inhabitants. Though the school, like much of the city around it, was eventually bombed anyway, the story turned into a legend, embroidered and embellished with new details in each telling.

Among those who grew obsessed by the pilot’s story was the Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari, who was born in Saida in 1967 and whose father founded and ran that very boys’ school for two decades. Now, Zaatari, whose artwork has long explored the subtle gaps in official histories, has taken the story as the subject of Letter to a Refusing Pilot, an elegiac and enigmatic three-part installation in the Lebanese Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale.

For decades, Zaatari had heard variations on the Israeli pilot story, but never knew for certain whether it was true. In 2010, however, the tale, which by now had acquired mythic proportions, came up during a public conversation between Zaatari and the Israeli filmmaker Avi Mograbi. Thanks to the circulation of the transcript of that talk in book form, Zaatari learned that the pilot at the center of the rumor was not only real, but still alive and living in Haifa. He arranged to meet the man, whose name was Hagai Tamir, in a bar in Rome (the mutual non-recognition of Israel and Lebanon having prevented them from meeting in either of their home countries).

In the half-light of the bar, Tamir revisited that day, explaining that he had been trained as an architect and had recognized that the building was either a school or a hospital by virtue of its boxy institutional profile. But the details—whether Tamir was in fact a Saida Jew (he was not)—didn’t seem to matter too much at that point. The former pilot, who was now in his sixties, declared that he had never really cared for planes as war machines. Instead, he told Zaatari, he had joined the Israeli air force because, ever since he was a kid, he had wanted desperately to feel what it would be like to be a bird.

In the Biennale’s Lebanese Pavilion, Zaatari explores the pilot’s story through three connected works: on one wall is projected a forty-five-minute film that is defiantly—or even challengingly—non-linear; on a small monitor is a shorter 16mm piece that shows the Saida hillside silently being destroyed by bombs; and between them is a single, precisely installed cinema chair, in which viewers are invited to sit. The lone chair, which is velvety red, seems to evoke a theater for one, or even, perhaps, serve as a stand-in for the workings of memory itself.

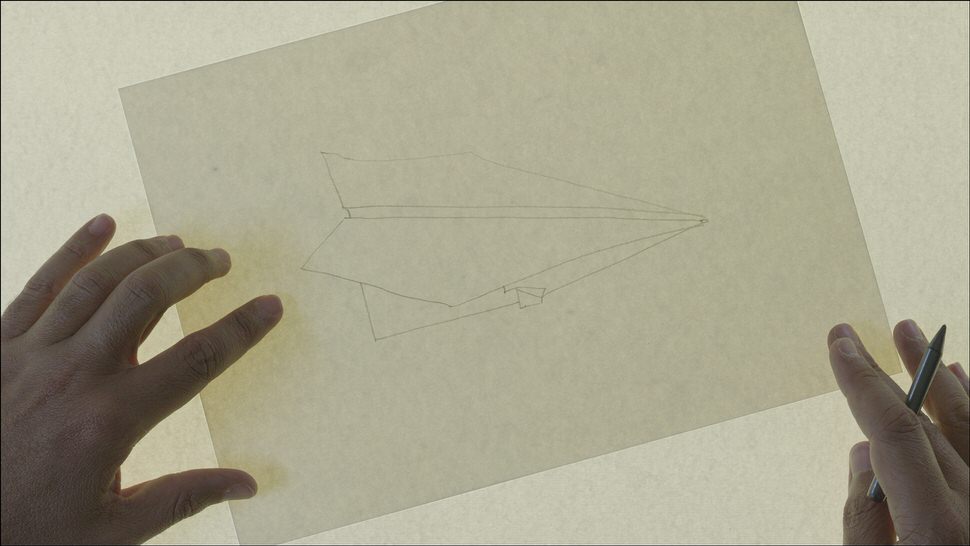

The longer film opens with two gloved hands—we can infer that they are Zaatari’s—delicately flipping through the pages of a vintage edition of The Little Prince, the much-adored 1943 tale of youthful existentialism by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (who, as it happens, was himself a famed war-time aviator who disappeared in 1944 during his last reconnaissance mission over the Mediterranean). Later in the film, the hands slowly and deliberately draw a rudimentary schoolhouse, and then sketch a paper airplane. They sensitively manipulate sepia-tinged family photographs, presumably of a younger Zaatari and his family on the grounds of the school in Saida. And they linger over the artist’s meticulous journal entries from the time of the Israeli occupation, when he was a teenager. These personal notes, inscribed in a standard calendar book, contain thick descriptions of some of the worst days of fighting in 1982, interrupted, sweetly, by names of films that he may have watched on those days (Death Hunt, starring Charles Bronson), references to the weather, or a note about a special friend who visited him at home. It is an unlikely account of war, one with the fingerprints of not only youth, but also its owner.

This sequence is followed by generous and meditative shots of kids moving through the hallways of the school today. Periodically, the sound of a drone and, sometimes, an airplane, crops up, ominously—like the intimation of an explosion to come, a nameless anxiety, or a vague and persistent half-memory. At one point, the camera lingers over a modernist sculpture in the schoolyard that, at first glance, approximates an abstract doughnut, but on closer inspection suggests two humans either embracing, propping each other up, falling into each other, or perhaps pushing against each other, as if in a slow-motion fight.

Advertisement

Finally, two schoolboys are shown climbing up to the roof, perched high above the city, where they fold the day’s schoolwork into elaborate paper airplanes. Occasionally, one of the boys—multiple viewings of the film left me convinced he is a stand-in for a younger Zaatari—is shot against a neutral backdrop handling a small reel-to-reel sound recorder (the kind one would use to, say, capture the sound of passing jet planes), loading film into his camera, or clumsily putting on a tie as Francoise Hardy’s “Comment Te Dire Adieu” plays in the background. For Zaatari, the song—it is infectious and irresistible—is surely one of the defining memories of 1982, and by that conceit, of the Israeli occupation. It is an unlikely, and even unforgettable, pairing.

A voice then reads this:

One week following Israeli’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, a pilot in the Israeli air force named Hagai Tamir flew over the site of the Saida Secondary School for Boys and refused an order to bomb it.

Much of the press material about Letter to a Refusing Pilot announces that the work is about refusal as an act, noting that its title is a reference to Albert Camus’ “Letter, to a German Friend,” in which the philosopher memorably pleads, “I should like to be able to love my country and still love justice. ” And yet this tidy summation doesn’t capture the force of Zaatari’s work. Through a collage-like accumulation of images and sounds drawn from past and present and past again, the film and installation—as with much of the artist’s work—skillfully excavates the life of a memory, complete with memory’s attendant lapses and instability. Interestingly, the pointedly lit cinema chair is positioned with its back to the longer film, so that it faces instead the 16mm barrage of bombs. By placing each one of us, alone, within the generous frame of the work, it seems to remind us that, not unlike the pilot, we are sometimes caught up in vexed circumstances beyond our control.

For a national pavilion at the Venice Biennale that might struggle under the expectation to show art with national bona fides—in this case for a famously fractious Lebanon—this degree of ambiguity is welcome. Rather than try to attach any fixed meaning to Lebanese identity or even Lebanese memories of the 1982 invasion, Letter captures an act of refusal whose meaning could be applied to the Israeli-Arab conflict, the current disintegration of Syria—indeed, to almost any confrontation today.

Many critics and art historians have noted that the slippage between political facts and fictions has become a leitmotif in much contemporary Lebanese art. The New York-based Lebanese artist Walid Raad’s The Atlas Group (1989-2004), for instance, a work that encompasses copiously detailed documents, photographs, and other miscellaneous traces from the Lebanese Civil War, is a paradigmatic case. Raad reminds us that in a country divided by dozens of sects, political allegiances, and ruling proxies, there is little possibility of consensus.

Zaatari—who has worked closely with Raad— is attracted to archival materials not as forms of established truth on the one hand or fiction on the other, but rather as markers of specific, personal experience. His various works involve photographs, notes, sound and video recordings, interviews, time capsules, and more—often drawn from his own fastidious personal archive.

He has also worked extensively with the material of others, perhaps most memorably the octogenarian Saida-based studio photographer Hashem El Madani. A current exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York features, in part, pieces of Zaatari’s research for the Arab Image Foundation, an idiosyncratic archive and organization (of which I am also a part) based in Beirut.

A typical Zaatari work—if there is one—might present a photograph of a page from an old journal or a letter exchanged between a prisoner in an Israeli jail and his family—but also capture the shadow that has fallen on the document at the very moment at which he photographed it.

Advertisement

For Zaatari, the meanings we attribute to historical materials can go well beyond their original significance, for these materials are bearers of multiple stories. With Letter to a Refusing Pilot, the artist not only realizes an improbable correspondence between two countries at war, but also reminds us that a simple act of refusal more than three decades ago belongs very much to the present day.

Letter to a Refusing Pilot, an installation by Akram Zaatari, is on view in the Lebanese Pavilion of the Venice Biennale through November 24.