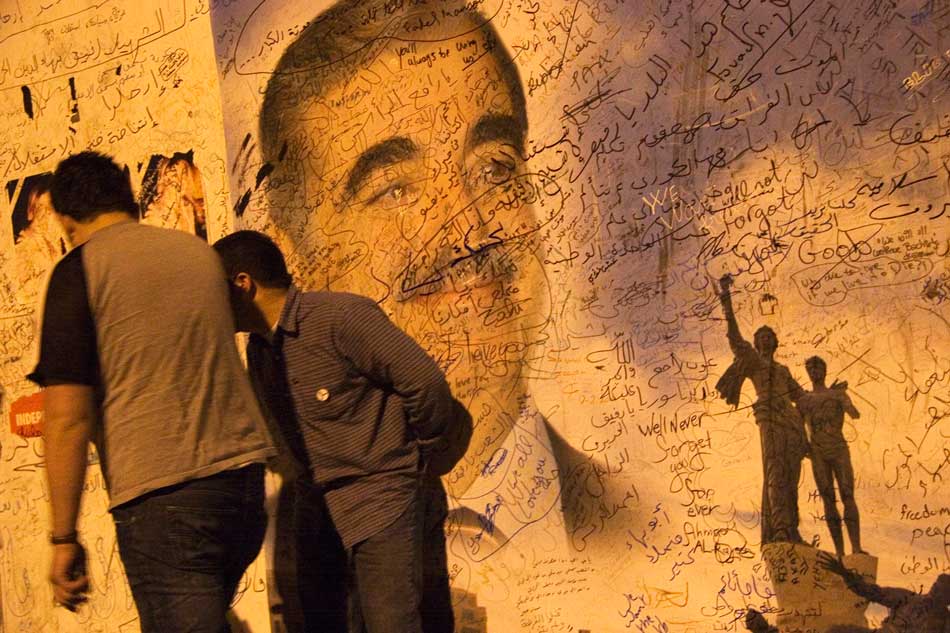

Lebanon’s Prime Minister Rafik Hariri was assassinated on February 14, 2005, when a 2,200-pound bomb exploded his car as it passed by the St. George Hotel on Beirut’s seaside Corniche. Hariri had recently disagreed with Syrian authorities over the terms of that country’s occupation of Lebanon, and speculation about who was behind the killing immediately focused on Syrian security forces, as well as their allies in Hezbollah. A fact-finding mission sent by the United Nations concluded that local police showed “a distinct lack of commitment” to solving the crime and worried that “the Lebanese investigation lacks the confidence of the population necessary for its results to be accepted.” Given the perceived inadequacy of local institutions, the UN appointed Detlev Mehlis, a German judge, to head an international inquiry into the killing. Mehlis published his preliminary findings in October 2005, though the investigatory commission dragged on for another four years.

Rabee Jaber’s novel, The Mehlis Report, published in Arabic in 2005 (just months after the preliminary report) and now expertly translated by Kareem James Abu-Zeid, takes place in the summer and fall following Hariri’s assassination. This was an especially anxious time in Beirut. The murder set off a movement demanding an end to Syria’s fifteen-year occupation, as well as a violent countermovement spearheaded by Hezbollah. Jaber’s novel begins on June 2, the day Samir Kassir, a prominent anti-Syrian journalist and historian of Beirut, was killed by a car bomb outside his home in Achrafiya, in the eastern part of the city. Further car bombs were to follow, targeting other anti-Syrian intellectuals and politicians. Jaber’s novel evokes this unsettled period with frightening precision. Like several of his other books, The Mehlis Report is held together less by its plot or characters than by its uncanny way of capturing the zeitgeist. It reads like a historical novel that happens to be about the very recent past.

The hero of this history is a sort of Lebanese everyman called Saman Yarid—his name is always given in full. He is a forty year-old unmarried architect from a family of local architects and his career is at an impasse; he only goes to the office because he doesn’t like being alone at home. He has a number of mistresses but no deep attachments to any of them. Yarid’s two sisters, who live abroad, urge him to leave Beirut, a city they expect to explode at any moment, but Yarid feels tied to the place for reasons he can’t fully explain. “A city thrives for a time, then collapses,” a friend tells him, hinting at parallels between Beirut and Yarid’s own family history. “A house flourishes for decades, then falls. The city is falling now too. Your problem is that you were born at a moment when the house is collapsing.” The more urgent reason Yarid stays in Beirut is that he, like most Lebanese, is waiting for the German judge to speak:

That white man with blond hair, Mehlis—he was keeping quiet. How long would he stay silent? At first they said until October 21, and then until October 25, and now they’re saying until December. What is this? Are they waiting until every living soul is gone from Beirut? How long will they wait? Don’t they know the truth yet? What’s this truth that can never be told? People are dying while the truth holds its tongue.

The Lebanese, divided into seventeen officially recognized sects, have struggled for a long time to agree on important truths about their country. Since 1920, when the French established Lebanon under a separate mandate, local historians have disagreed about the most basic elements of the national narrative: Was Lebanon a historically distinct place, set apart from its Syrian and Arab surroundings (as many Maronite Christian historians have contended), or was its history most accurately viewed as one short chapter in a larger, Arab-Islamic story? The absence of consensus on such matters “leaves the question of the Lebanese past in the realm of polemics, rather than the realm of history,” as Kamal Salibi once wrote in his classic work on the subject, A House of Many Mansions. In this sense, the hopes many Lebanese initially placed on a foreign judge to solve the Hariri killing were merely another symptom of their mutual distrust for one another (the reflex, in times of crisis, to look abroad for salvation is another constant in Lebanese history). Jaber’s novel does not try to answer questions about the murder; his novel is not a critique of the Mehlis investigation. In fact, he is always careful to remind us that what we are reading is a fiction, or even a fantasy. At the same time, Jaber clearly believes that novelists can contribute in significant ways to debates about the past. But what can works of the imagination tell us about the truths of history?

Advertisement

Jaber is an astonishingly prolific writer. Still in his early forties, he is the author of seventeen novels—The Mehlis Report is the first to be translated into English—and also edits the weekly cultural supplement of al-Hayat newspaper. He works in a number of genres, but historical fiction is the one to which he has devoted the most time and thought. The genre is well-established in Levantine letters, beginning with the medieval romances of Jurji Zeydan—a sort of Walter Scott for the Arabic novel—and extending through the novels of Amin Maalouf; Jaber shares with Maalouf a delight in stories that defy conventional ideas about identity and the relations between East and West. His novels have treated, among other subjects, the history of Levantine emigration to America (America, 2009), the adventures of a captive Druze in late Ottoman Serbia (Druze of Belgrade, 2010), and eleventh-century Andalusia (The Journey of a Man from Granada, 2002). One wishes, at times, that Jaber were more pointed in his retelling of these histories. His plots are often aimlessly picaresque and he has an antiquarian’s fondess for irrelevant oddities—his descriptions of meals, for example, read like recipes.

But the place Jaber keeps returning to, and the place that has inspired what seems to me his sharpest writing, is Beirut. The same year he wrote The Mehlis Report, Jaber also published Berytus: An Underground City (2005) (“Berytus” is the original name of the Phoenician city of Beirut); and both books came amid his work on Beirut, City of the World (2003–2007), a separate trilogy of thick novels about the city. The trilogy traces Beirut’s evolution, by way of one elite family’s history, from a small port city in the early nineteenth century to the cosmopolitan capital of the present. Early in the opening novel, the narrator-turned historian explains:

I always try to take the reader back to the world of ancestors, so he might see what I see, so he might feel what I feel. As if he were to look at the newly renovated City Hall and see, within the depths of the modern, shiny-glassed building, that other, invisible, dun-colored building, with its Ottoman-style terracing, as it was designed by Youssef Aftimus during the French Mandate and as it is preserved for us in the photograph taken by the Armenian Ouzounian in 1928.

This is a recurring scene in Jaber’s fiction: a character stops in front of one of Beirut’s modern buildings and tries to remember what used to stand there. (Classical poetics in Arabic calls this scene the nasib: a nomad-poet halts at an abandoned desert campsite and, while figuratively sifting the ashes through his fingers, recalls the good times he once had there.) The Mehlis Report is punctuated by Saman Yarid’s walks through the downtown district of Beirut and the neighborhood of Achrafiya, where he lives. These excursions are diagrammed with an exhaustive and occasionally exhausting realism. Abu-Zeid notes in an interview that translating the novel meant spending a great deal of time with Beirut street maps. Even the conversations between Yarid and his mistresses often circle back to local geography, as the couples try to remember buildings, architects, and landmarks that no longer exist. “The restaurants change their names with each passing season,” Yarid grouses to himself on one of his walks. “It’s not good. You lose your bearings that way. They ought to carve the old names above the doors.”

Joyce famously boasted that his ambition in Ulysses was to give a picture of Dublin so complete that if the city were one day destroyed it could be reconstructed out of his novel. The same ambition seems to animate Jaber’s mapping of Beirut, where the possibility of destruction is not so remote as it might seem. It happened to the Hellenistic city in 140 BCE, then again in the earthquake of 551, and a third time during Lebanon’s fifteen year civil war (1975–1990). At the end of that conflict, the city’s downtown lay in ruins. Rafiq Hariri, who had earned billions in the Saudi construction business and was newly elected as Lebanon’s prime minister in 1992, set up a real estate company called Solidere to oversee the rebuilding of the city center (later the scene of his own assassination). Solidere began its work by razing most of the district to the ground, uncovering in the process a mille-feuille of archeological strata from Phoenician, Greek, Roman, Arab, and Ottoman Beirut. Ten years later, a glittering new downtown stood in place of the old. So the double-vision that Jaber gives his characters and readers—the ability to see specters of the past behind the solid structures of the present—is a symptom of the vast and sudden transformation Beirut has undergone since the end of the civil war.

Advertisement

Jaber seems to think of fiction primarily as a speculative way of writing history. It is not so much concerned with what happened as with what might have happened. He views the past not as an accumulation of facts (though the facts are important), but as a field of unrealized potential, a series of paths not taken, or missed opportunities. The ghostly buildings of old Beirut, or the ruins of those damaged during the civil war, are reminders that parts of the city’s earlier history remain unreconciled with or cut off from the present.

Jaber’s concern with missed opportunities extends to his characters. Many of his novels feature characters who are kidnapped, disappeared, or otherwise removed from history. The later chapters of The Mehlis Report are narrated by Saman Yarid’s sister, Josephine, who was abducted, then killed during the war. From her vantage point in the hereafter, she watches her brother fritter his life away while she tries to understand why her own turned out the way it did (in Jaber’s version of the afterlife, everyone is engaged in writing his or her memoirs). One of the people Josephine meets at the end of the novel is Rafik Hariri, another of history’s abductees. The former prime minister isn’t presented in the obvious ways; he is neither a vengeful spirit nor the victim of his own hubris. Instead, he is a kind of dislocated observer, curious to see how his plan of rebuilding Beirut in a grand style will eventually pan out. The question of who killed him hardly seems to matter. And it is unlikely the Lebanese themselves will agree any time soon about the perpetrators. In 2009, after four years of inconclusive work, the UN investigative commission was superseded by a UN Special Tribunal, whose efforts have been consistently called into question by Hezbollah and its allies. The prosecutor handed down indictments of four Hezbollah members in January, 2011; their trial (in absentia) has yet to begin.

Berytus: An Underground City, scheduled to be published in English next year, also in Kareem James Abu-Zeid’s translation, seems inspired by the archeologists’ discovery of multiple Beiruts beneath the real one. It begins with a self-consciously gothic premise: Jaber is dining one night with friends downtown when they are approached by a man whom he recognizes as a former security guard from the al-Hayat offices, but who now “looks uncertain of his own existence” and begs the novelist to listen to his story. The guard claims to have fallen into a hole while working at the old City Palace cinema, an especially haunted spot in Jaber’s imagination, and to have landed in an underground city that lies beneath the more familiar one. The rest of the novel reads like an exotic travelogue—it includes a romance that seems to have strayed from a work by the turn-of-the-century French novelist Pierre Loti—whose pleasure lies in Jaber’s ingenuity in making this alternate world anthropologically plausible. What do these cave dwellers eat? What do they use for money? How do they procure light? Underground Beirut turns out to be a funhouse version of the actual city: the food is terrible and the inhabitants have forgotten about religion, but both are cities of emigrants with dreams of a better life elsewhere. Here again, Jaber’s fiction seems designed to remind us of the precarious nature of the world we take to be natural and even inevitable. One look into a Phoenician dig pit suggests otherwise.

At one point in Berytus, the security guard-turned-storyteller offers Jaber a riddling summation of the novelist’s own method. “What is it you’re always saying in your books? That whatever happens was written.” “Written,” maktoub: the Arabic involves a pun Jaber is especially fond of. On the surface, the phrase uses a conventional expression for fate, and means that whatever happens was bound to happen. This is precisely what Jaber does not say in his books, of course, though it is easy to see how his interest in historical documentation might lead unwary readers astray. Instead, his fiction makes a more subtle argument: not that whatever happens is fated (maktoub), but that whatever happens is recorded (maktoub) somewhere, and might therefore be rescued from the catastrophe of actual history. It is an especially appealing thought, given Lebanon’s still unreconciled past and conflict-ridden present.

Rabee Jaber’s The Mehlis Report, in a translation by Kareem James Abu-Zeid, has just been published by New Directions.