On Wednesday, July 10, 2013, President Barack Obama presented the 2012 National Humanities Medal in the East Room of The White House. Among the twelve medal recipients was the Review’s editor, Robert B. Silvers, who was cited for “offering critical perspectives on writing. As the editor and co-founder of The New York Review of Books, he has invigorated our literature with cultural and political commentary and elevated the book review to a literary art form.”

In a presentation earlier in the day, Silvers addressed the staff of the National Endowment for the Humanities, and spoke about the influence of Edmund Wilson on the Review:

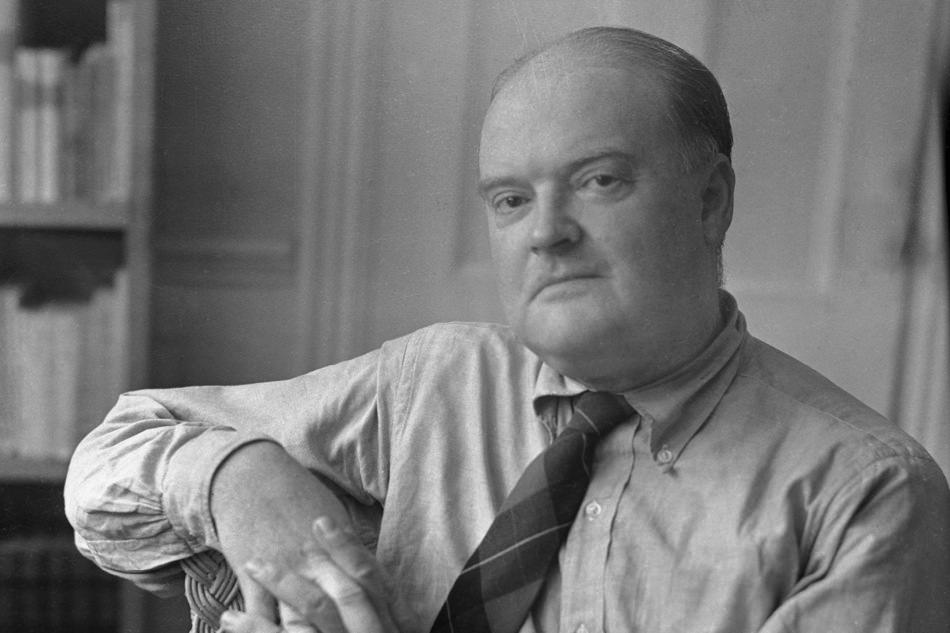

I think the person we all admired most, and who meant a lot to us, was Edmund Wilson. He was the author of a book called Axel’s Castle, which was still one of the great introductions to modern writing; to Rimbaud, to Eliot, to Pound, to Joyce and Proust. And we knew that in the Thirties he had written extraordinary reportage and reflections on the Depression, collected in works like The American Jitters and The American Earthquake. He wrote an astonishing variety of books, including the only great study of civil war fiction and prose, Patriotic Gore. And he was astonishing as well in his willingness to take on difficult subjects—learning Russian to write about Russian literature and politics, learning Hebrew to write about the Dead Sea Scrolls, learning Hungarian to write about Hungarian poetry.

So you can imagine how excited we were when he wrote for us fifty years ago when we started The New York Review. At that time everyone was doing interviews. There was a magazine called Interview. And he did an interview with himself in our second issue. Referring to a German poet and writer named Johann Peter Eckermann, who had published his conversations with the aged Goethe, he called it “Every Man His Own Eckermann.” And in that interview he was pretty critical, both of a promotional atmosphere in New York culture generally and what he saw as a confining atmosphere in scholarship.

He later wrote for us an extraordinary essay called “The Fruits of the MLA,” about excessive narrowness in the editing of texts of American literature, which were being issued very expensively. That led to the Library of America. And the great thing about him was his intellectual daring. He wrote about the Iroquois Indians. He wrote about Haiti. All in his beautiful, expository prose, which was sympathetic and yet skeptical at the same time. And so he meant a lot to us in getting our paper going, and I think we still have a great deal to learn from him.

Edmund Wilson’s interview “Every Man His Own Eckermann” appeared in the second issue of The New York Review of Books in June 1963. A full list of his contributions to the magazine can be found here.