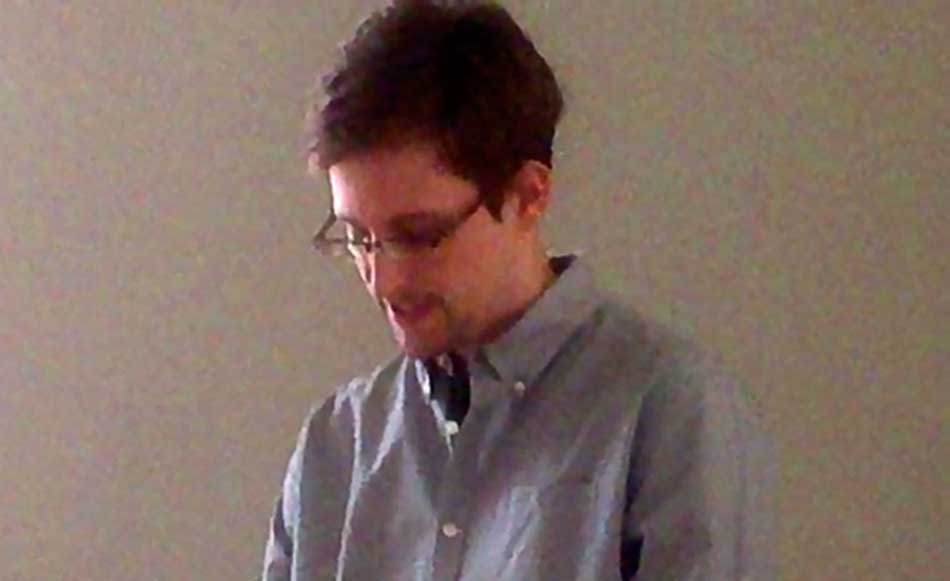

Traitor, hacker, high-school dropout, narcissist: Edward Snowden has been called many things since coming forward as the source who gave documents to The Guardian showing that the National Security Agency has been collecting telephone and Internet data on hundreds of millions of Americans, revelations that members of the Senate Judiciary Committee pressed the NSA to explain at a contentious hearing in Washington last week. The one thing that Snowden’s detractors have insisted he does not merit being called is a whistleblower. “I don’t look at this as being a whistleblower,” said Senator Dianne Feinstein, Chairwoman of the Senate Intelligence Committee. “Why is media using sympathetic word ‘whistleblower’ 4 Edward #Snowden, who leaked secret #NSA program?” tweeted Richard Haass, President of the Council on Foreign Relations.

In fact, most journalists and editors haven’t been calling him that, instead referring to Snowden as a “leaker.” This is the label the Obama administration has applied to the record number of officials it has prosecuted in recent years for disclosing classified information to unauthorized recipients, among them Pfc. Bradley Manning, who on July 30 was acquitted by a military judge of the charge of “aiding the enemy” but convicted on multiple other counts for turning over some 250,000 US diplomatic cables and 500,000 army reports to Wikileaks. Snowden has managed to escape prosecution, at least for now, after being granted temporary asylum by the Russian government on August 1, a move that infuriated the White House and has fueled speculation that President Obama will cancel a planned visit to Moscow this fall. [Update: On August 7, the White House, citing Russia’s “disappointing decision,” announced that the visit was cancelled.]

In a memo to reporters circulated back in June, the Associated Press spelled out why “leaker” was the more appropriate way to refer to both Snowden and Manning. “A whistle-blower is a person who exposes wrongdoing,” explained Tom Kent, the AP standards editor. “It’s not a person who simply asserts that what he has uncovered is illegal or immoral.” For Snowden to have asserted that the NSA’s spying programs “corrupt the most basic notion of justice” and that “the US Constitution marks these programs as illegal” without a strong basis for saying so would indeed seem to undercut any claim that he is a “whistle-blower.” But as suggested by the sudden push in Congress to rein in the NSA’s telephone surveillance program, Snowden’s charges have struck a chord. More to the point, even his most unsparing critics would be hard pressed to deny that the activity Snowden exposed raises serious ethical questions about the NSA and that he reasonably believed that what he revealed was illegal. According to Louis Clark, president of the Government Accountability Project, the nation’s leading advocacy group for whistleblowers, this is the standard that employees who go public with allegations of abuse or wrongdoing must meet. Clark considers Snowden a prototypical whistleblower. When I repeated to him the Associated Press’s view, Clark said, “They flat-out have it wrong. And they’re allowing the administration and its defenders to better control the story by substituting the loaded term ‘leaker.’”

Of course, identifying someone as a whistleblower is equally loaded, in a positive way: it evokes the image of an intrepid truth-teller who sounds the alarm from inside an organization, often at great personal risk, in order to safeguard the public interest. “Muckraking by insiders” is among the earliest definitions of such conduct, appearing in a 1971 article by Taylor Branch in The Washington Monthly that was reprinted in Blowing the Whistle, a volume of essays and profiles published the following year that marked the first book-length treatment of the subject. In the book, Branch and his co-author, Charles Peters, traced the term whistleblowing back to “the bulbous-cheeked English bobby wheezing away on his whistle when the maiden cries ‘Stop, thief!’ By the 1960s, when it entered the popular lexicon, “whistle-blowing” had acquired a more glamorous aura, reflecting the adversarial spirit of the age. There is some irony to this, since whistleblowers tend to be not crusading radicals but rather by-the-book organization people who believe they are acting to preserve the integrity of the institutions they work for or the governments they serve, as the sociologists Myron Peretz Glazer and Penina Migdal Glazer concluded in their 1989 book, The Whistleblowers. According to another study, “They are, if anything, too trusting of the organization’s willingness to respond to their concerns”—and tend to discover otherwise the hard way. So it was with Frank Serpico, a police officer who reported evidence of rampant corruption within the NYPD to his superiors in 1967 and, a few years later, after nothing happened, disclosed what he’d witnessed to a reporter at The New York Times.

Advertisement

Ideally, this is what all whistleblowers do, going first to their superiors or other regulatory agencies and turning to the press only if their concerns are ignored. Snowden, of course, did not follow this script and went immediately to the media, a fact some have seized on to discredit him. “He went outside all the whistleblower avenues that were available to anyone in this government, including people who have classified information,” Mike Rogers, chair of House Intelligence Committee, noted on Meet the Press. But Rogers neglected to mention that several NSA whistleblowers have tested these internal channels in recent years, airing their concerns about unwarranted wiretapping before Congress, the Department of Justice, and the inspector general’s office. Their efforts eventually sparked a federal investigation—not of the NSA’s conduct but of their own.

One of the whistleblowers, Thomas Drake, was served with a ten-count felony indictment in 2010, charges that were eventually dropped, but not before his house was raided and his career destroyed. In recent years, laws have been enacted to protect from reprisal federal workers who try to expose wrongdoing, most notably the Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act, which President Obama signed last year. But the law does not cover intelligence workers, an omission that William Binney, another NSA whistleblower, believes was not lost on Snowden. “I think he saw and read about what our experience was, and that was part of his decision-making,” Binney recently told USA Today. (Though Binney was never prosecuted, in 2007 federal agents also raided his home and confiscated his computer equipment and other personal possessions while pointing a gun at his head.)

Quite apart from the method of Snowden’s disclosures is the thorny matter of what he revealed. What if the wrongdoing that Snowden has exposed is not recognized as such by many of his fellow citizens? The absence of such a consensus concerning the NSA’s surveillance activities, which polls have shown many Americans regard as unobjectionable, evidently helped persuade the Associated Press not to designate him a whistleblower, a logic the news organization also applied to Bradley Manning. “Whether the actions exposed by Snowden and Manning constitute wrongdoing is hotly contested, so we should not call them whistle-blowers on our own at this point,” the AP memo stated.

By this standard, however, it’s not clear whether any national security officials who have revealed abuse or misconduct would qualify as whistleblowers. Consider Daniel Ellsberg, whose decision to pass a copy of The Pentagon Papers to The New York Times and other newspapers in 1971 is widely seen as an honorable act of whistleblowing today. As the essay by Taylor Branch on Ellsberg in Blowing the Whistle makes clear, opinion was far more divided at the time the documents were published. Branch mentions a “dovish foreign-policy veteran” who told him he thought “our mutual friend Ellsberg was crazy,” an opinion “widely held in the foreign-policy field.” While opponents of the Vietnam War embraced Ellsberg as a courageous hero, many hawks viewed him as a traitor whose disclosures benefited America’s enemies in the middle of a war, a schism that is not dissimilar from the public debate about Snowden today.

It is always easier to recognize and appreciate whistleblowers in retrospect than in the heat of the moment, particularly when their revelations concern policies that have been justified on national security grounds, as is the case with the NSA’s surveillance activities. (Although at last week’s Senate Judiciary Committee hearing, Senator Patrick Leahy sharply questioned this rationale, stating that the classified list of “terrorist events” the NSA claims it has detected—a list he has seen—was not a convincing enough rationale for its privacy violations.)

In view of America’s deep tradition of individual liberty and distrust of government, one might suspect that whistleblowers like Snowden are more likely to win sympathy in the US than in other countries. But the evidence suggests the opposite. In answer to the question of whether “people should support their country even if the country is in the wrong,” more Americans said yes than citizens of eight European countries, the International Social Survey Programme found in 2003. Asked whether “right or wrong should be a matter of personal conscience,” Americans came in next-to-last. According to the sociologist Claude Fischer, comparative surveys in subsequent years have consistently shown that US citizens are “much more likely than Europeans to say that employees should follow a boss’s orders even if the boss is wrong”; more likely “to defer to church leaders and to insist on abiding by the law”; and more likely “to believe that individuals should go along and get along.”

As all of this suggests, Americans are far more conflicted about people who reveal unpleasant secrets about the government and large corporations than the romantic image of the heroic whistleblower would have us believe. I discovered this not by reading surveys but by interviewing Leyla Wydler, a stock broker from Houston, Texas, who, back in 2003, warned the Securities and Exchange Commission and several newspapers that her former employer, the Stanford Financial Group, was committing fraud. In textbook fashion, Wydler first expressed concern about the financial products she was instructed to sell to management, which responded by firing her, and then to public agencies and the press, which ignored her. As C. Fred Alford has shown in his book Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power, this is how stories like hers often turn out, with the person who spoke out punished and ostracized.

Advertisement

By the time I met Leyla Wydler, in 2009, the $7 billion fraud perpetrated by Stanford—the second largest Ponzi scheme in U.S. history—had finally been exposed, not because her warnings in 2003 had been heeded but because of an investigation launched five years later, after Bernard Madoff’s Ponzi scheme collapsed. But instead of feeling vindicated and embracing her status, Wydler told me she didn’t want to be labeled a whistleblower, which in her mind carried a whiff of disloyalty that reminded her of the way her former coworkers had made her feel: like she’d betrayed both them and her industry. What Wydler experienced firsthand is what Edward Snowden’s critics appear to have forgotten: namely, that even when exposing indisputably illegal conduct, a whistleblower is not necessarily an enviable thing to be in America.