“Bill Brandt…is to photography what a sculptor is to a block of marble,” wrote Lawrence Durrell. “His pictures read into things, try to get at the hidden presence which dwells in the inanimate object. Whether his subject is live or not—whether woman or child or human hand or stone—he detaches it from its context by some small twist of perception and lodges it securely in the world of Platonic forms.”

Bill Brandt was one of the great modernist photographers of the twentieth century; Brassaï called him “a master.” Born in Hamburg in 1904, he took up photography in Vienna in the late 1920s. He then moved to Paris, where—thanks to an introduction arranged by Ezra Pound, whose portrait he had made in 1928—he spent several months as an apprentice in the studio of the Surrealist photographer Man Ray. During his time in Paris, Brandt also discovered the work of two other photographers who became profound influences on his own approach to making images: Eugène Atget and Brassaï, whose landmark book Paris by Night (1933) was the model for Brandt’s second book, A Night in London (1938).

In 1934, Brandt settled in London—and he died there in 1983, having spent a half-century creating a vast body of distinct work that has influenced countless photographers since, from Robert Frank to Martin Parr. About 150 of his prints—including examples of his early images of British society and landscape, his photographs of wartime London, his hundreds of portraits of writers and artists, and his progressively abstract series of nudes—were on display in MoMA’s recent exhibition “Bill Brandt: Shadow and Light.” One of them, Northumbrian Miner at His Evening Meal (1937), appears in the September 26 issue of The New York Review, and additional images can be seen in this slide show.

“I believe this power of seeing the world as fresh and strange lies hidden in every human being,” Brandt wrote. “In most of us it is dormant. Yet it is there, even if it is no more than a vague desire, an unsatisfied appetite that cannot discover its own nourishment.” Through photography, he believed, it was possible for people “vicariously, through another person’s eyes,” to “see the world anew. It is shown to them as something interesting and exciting. There is given to them again a sense of wonder.” Brandt also believed in the photographer’s complete freedom to experiment in the darkroom: “There are certainly no rules governing how a picture should be printed. Some should be dark and muddy, some very white and underprinted.” He often cropped his photographs and retouched them liberally, and over time he developed a preference for very heightened contrast, even when it came to making new prints of his early work.

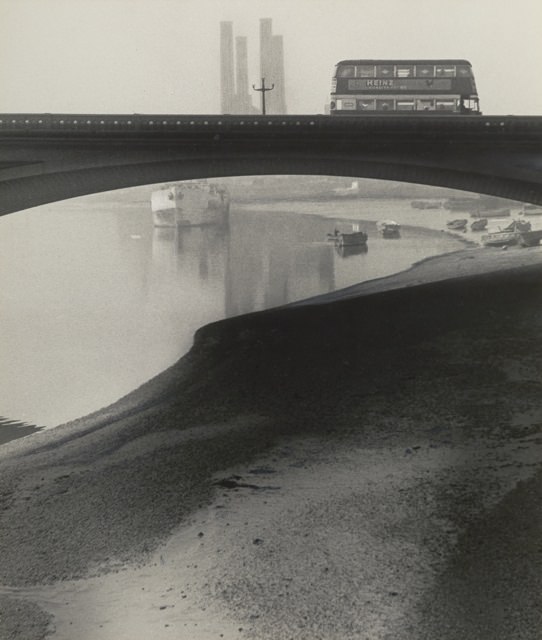

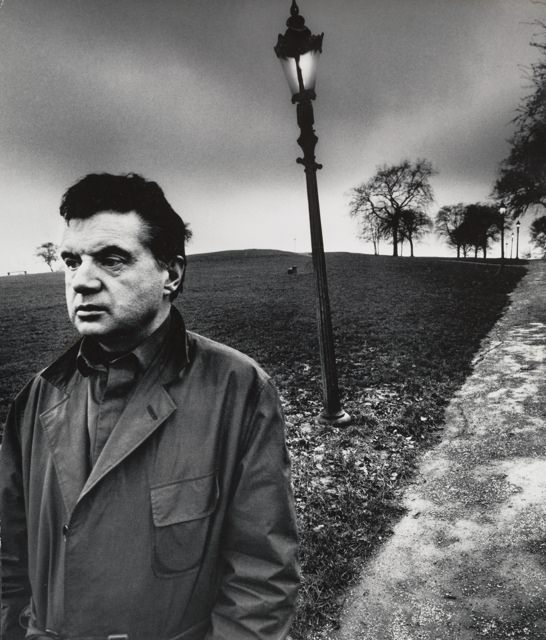

Brandt wanted to infuse in his photographs with “atmosphere,” which he believed was “the spell that charged the commonplace with beauty” and revealed the subject as “familiar and yet strange.” One of his extraordinary talents was to make even his early documentary images mysterious. His portraits of parlormaids in wealthy London households show them engaged in everyday activities—opening curtains, standing at table, preparing a bath—but there is also a novelistic quality to these images, as though they have been captured at a fixed point in a story. Brandt often shot his subjects from below with a wide-angle lens, making them loom large and statuesque in their environments, as in his austere portrait of Francis Bacon, who appears almost monolithic against a backdrop of leaning streetlamps and a darkened sky. The humanity of his subjects is suggested in their furrowed brows or their gazes, while their bodies seem to be as unyielding as stone. At the same time, Brandt humanized even the most urban and industrial landscapes, bringing out the curves of the River Thames and its sandy shoreline underneath the Battersea Bridge in a way that looks forward to the fleshy shapes of his later nudes.

Versions of many of the photographs from the MoMA exhibition have appeared in previous collections of Brandt’s work, but not always with good production values. The reproductions in the exhibition catalog are exceptionally beautiful, and are accompanied by informative essays by the curator Sarah Hermanson Meister and others. Another collection of Brandt’s work—Brandt Nudes: A New Perspective, which brings his two previous volumes of nude photographs together into one—has also been published recently. It is filled with gorgeous reproductions as well, and includes Lawrence Durrell’s original preface to the first volume of nudes, along with commentaries by Mark Haworth-Booth.

In a 1981 review of Brandt’s second book of nudes, Clive James wrote in The New York Review, “Looking at these pictures, even the most clueless viewer will sense himself in the presence of a rare concentration of thought and feeling.” But it was James’s verdict that “in treating the human body as a sculptural form Brandt was unable to avoid the gravitational pull of sculpture itself. Warm bottoms become cold Brancusis. Hips turn into Arps.” These images show Brandt at his most experimental, abstracting swaths of the human figure with his camera frame and wide-angle lens and finding an odd beauty in the often harshly distorted surfaces and shapes. He explained his approach to the nudes this way: “Instead of photographing what I saw, I photographed what the camera was seeing. I interfered very little, and the lens produced anatomical images and shapes which my eyes had never observed.” The MoMA exhibition emphasized the sculptural quality of these images, displaying them in an arrangement of different-sized ears, shoulders, hands, knees, breasts, bottoms, and toes together on two walls.

Among the most exquisite photographs from the exhibition was Crystal Palace (1938)—an early nude, but not one of flesh and blood. In this image, Brandt’s subject is a naked statue in a London park. Her curvaceous stone body is coated with white frost and resembles voluptuous flesh. The frost accentuates the folds of the fabric that she holds at her groin, and also highlights the ringlets of her hair, her nose, lips, nipples, fingers, and toes. The pedestal she stands on isn’t visible in the frame, and so her feet appear almost to be resting on the ground as the wind blows through the branches of the trees behind her. The magic of Brandt’s photograph is to make this inanimate sculpture look startlingly lifelike and vulnerable, and it gave this viewer goosebumps.

All images are copyright © 2013 Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.