In high school, I took a weekly drawing class at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and every Friday afternoon I’d stand—reverent, transfixed—in front of Magritte’s The Empire of Light. In the painting, one of several similar works done during the 1950s it is night; a street lamp illuminates a city block; lights glow behind a few windows of the houses whose occupants are presumably unaware that, just above their neighborhood shrouded in darkness, is an expanse of sunny blue sky, dotted with cottony clouds. How enthralling it seemed to me, how magical and deep, how suggestive of a meaning that was obviously profound yet tantalizingly elusive.

Now, when I look at that painting in reproduction, and at the works displayed in the new MoMA show on Magritte, I can’t recapture the faintest hint of my former emotion. A locomotive comes roaring out of a fireplace. A pair of boots morphs into a pair of feet, with toes. A seated man in hat and a blanket has a birdcage instead of a torso. Two lovers kiss, their heads swaddled in white cloth. Magritte’s paintings exude the mysterious and the improbable, but when I visited the exhibition, what seemed most mystifying and unlikely to me was that there had been a time in my life when he was one of my favorite painters.

I’m not disparaging Magritte’s gifts—his technical skill, the sense of humor and of the absurd that he shared with his fellow Surrealists—nor questioning the pleasure that people (of all ages) have obviously taken in the exhibition. Rather I am trying to understand a phenomenon that many of us have experienced: at a certain point in our lives, a work of art speaks to us with a powerful, intimate voice. But years later we may be surprised to discover that this voice has gone silent.

One measure of a masterpiece may be the impression it gives of changing along with us, of growing as we grow, so that each time we return to it, we discover something new—some aspect we missed until an event in our lives attuned us to some unsuspected aspect of a work of literature, a painting, a film. I’d always thought that Katherine Mansfield’s 1922 short story, “The Daughters of the Late Colonel,” was about the relationship between two dotty elderly sisters until the loss of a close relative made me realize it was also about the impossibility of fathoming the mystery of death. I’d at first seen only the sex in Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris and only later noted the (one might think unmistakable) way in which everything in the film is shadowed by the suicide of the wife of the Marlon Brando character. Each time I watch Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, it seems like something else: a thriller, a study of the desire to transform every new love into a replica of an old one, a version of the fairy tale of Sleeping Beauty. Recently I saw Vertigo again, and it struck me that it was the director’s pained exploration of sexual fetishism: the fate of one doomed to fall in love with a hairstyle, a suit, and only secondarily with the person who wears it. Leaving the Magritte show, I passed the Max Beckmann triptych, Departure, that hangs in the fifth-floor lobby, and saw details—a part of a face or a figure—that I’d never noticed and that I found original and newly exciting.

But what about art that, like Peter Pan, refuses to grow up? What keeps a work attached to a particular age, a time we cannot revisit in order to recall why we so loved it? This is often the case with books about childhood and adolescence, which are of natural interest to kids and teenagers. Often such books have less to offer adults, though the brilliant exceptions—among them, Huckleberry Finn, The Diary of Anne Frank, A High Wind in Jamaica, David Copperfield—may seem even more meaningful when we read them as grown-ups.

We may also lose our early love for works that we only later realize are so marred by clichés, populated by stereotypes, and repulsively bigoted that we can no longer enjoy them, even if we make allowances for the attitudes of the period in which they were created. Not long ago, I watched the 1943 film version of Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence, a novel based loosely on the life of Paul Gauguin. As a child I’d loved the cinematic depiction of the painter’s romantic flight to—and tragic death in—the South Seas; I think it may have been one of the things that made me want to become an artist.

Advertisement

But this time I noticed that the tag line on the cover of the DVD was “Women are strange little beasts,” and that the movie suggests that these little beasts need to be kept in line and properly subservient by whatever means necessary. Once our hero arrives in Tahiti, the depiction of the islanders and of the girl who is given to him as a wife is appalling. I’m reminded of the fact that my enthusiasm for Gauguin crested around the same time as my affection for Magritte, while my admiration for Gauguin’s housemate, Van Gogh, has grown steadily over the years. For reasons I cannot explain—it’s the mystery of art—Van Gogh’s work seems to me more inspired, more beautiful and moving each time I see one of his canvases.

Perhaps something romantic about adolescence itself attracts young people to the exotic, to the magical, the supernatural and paranormal—the sort of fantasies that Magritte portrayed. Perhaps this attraction has to do with our growing awareness that we have outgrown a phase of life—childhood—when the lines between the real and the magical are blurred; by the time we reach adolescence, they have already started to sharpen.

As a child, I loved films in which there was an element of magic—Bell, Book, and Candle (1958), One Touch of Venus (1948), and René Clair’s I Married a Witch (1942)—films that provided something like what younger readers today find in the Harry Potter novels. My generation was fond of Carlos Castenada’s books about the Mexican shaman Don Juan, who took locally sourced psychedelics, spouted metaphysics, and performed daredevil stunts like a Central American version of a swordsman in a Chinese martial arts film. I’d stopped reading Castenada long before his fieldwork methods were called into question by his fellow anthropologists, who suggested that Don Juan may never have existed. For sentimental reasons, I’ve kept the Don Juan books in my attic. But I’m sure I will never reread them.

Magritte’s images are magical, and if their “meaning” eludes us, what we get instead is a visual and cerebral pop as the absurdity of the image—how could those leather boots be growing ten little human toes?—comes into focus. It’s a bit like getting a joke, which is pleasant to do in a museum until you reach a point when you want something more from art: the deeper pleasure we receive from Carpaccio, Velasquez, Jackson Pollock, the fifteenth-century Sienese painters. Of course we admire something different about each artist: the few brushstrokes with which Rembrandt willed a ruffle or a pearl onto a canvas, the twisted trees on the bare hills among which the Master of the Osservanza set his images of miracles in progress.

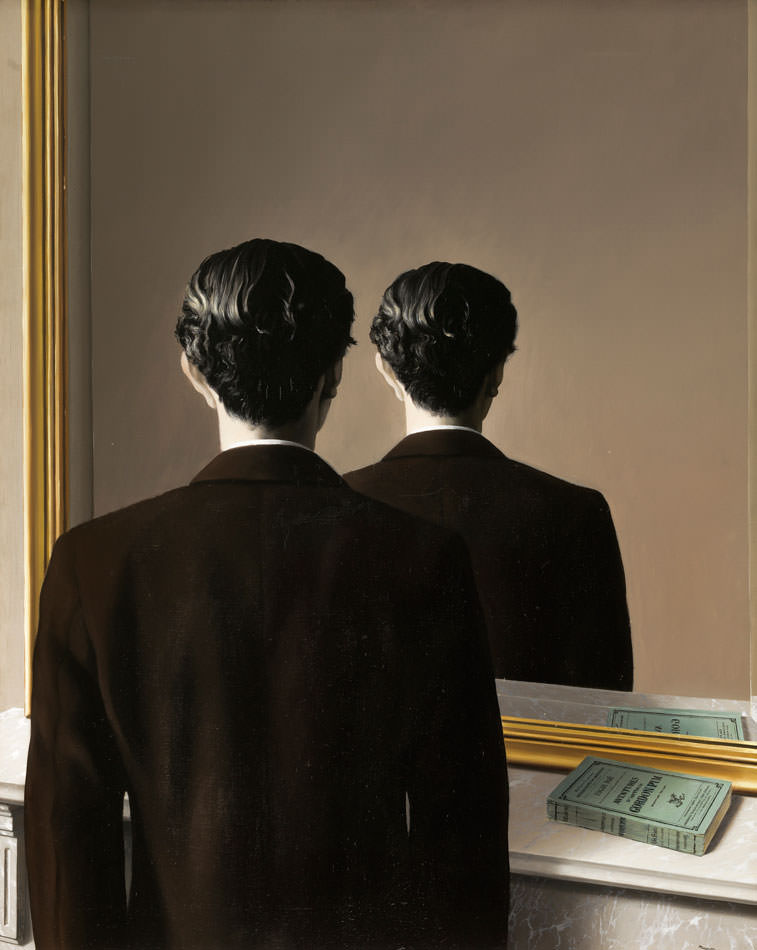

What strikes the young person as meaningful may seem pretentious to an adult. It doesn’t help that Magritte called one of his paintings The Human Condition. In it he depicts an easel before a window; the scene outside the window merges with the painting on the canvas, the edges of the “canvas” barely perceptible beneath the larger landscape.

Magritte did several drawings and two paintings of The Human Condition. In the one in the current show, from 1933, the landscape resembles a background one might find in Netherlandish art. In a later version, done in 1935, there’s another easel, another window, another landscape stretching across the painting within a painting. This time it’s a seascape, not particularly detailed or interesting, and in any case our attention is being hijacked by an object, rather like a black bowling ball, that makes us think of Salvador Dalí or Giorgio de Chirico rather than the human condition.

Until I began to write this essay, I’d had no idea that there was more than one Magritte painting entitled The Empire of Light. I’d thought that the only painting of the street-lamp and houses at night and the sunny sky was the one I’d seen in the Museum of Modern Art when I was a girl. So I was surprised to see, on the Internet, several paintings with that title, with different configurations of houses and neighborhoods and trees, but the same general idea: street lamp, night scene, houses and trees below; sunny sky above. (None of these versions, including the one I knew growing up, is in the MoMA show, which deals with an earlier part of his career.)

Advertisement

At first I felt disappointed, even slightly betrayed. So what if the painting was no longer a personal favorite? I still didn’t relish the idea that what I’d experienced as a private communication with a singular work of art was actually an encounter with some sort of commodified franchise. But after a while I found myself thinking about it another way. I like the vision of Monsieur Magritte, who so enjoyed disappearing into that streetscape poised between day and night, and who was so reluctant to leave that particular recurring dream, that he kept painting it—like Cimabue and his Crucifixions, like Monet and his haystacks, Munch and his screams, like any artist who remains obsessed with and begins to inhabit the imaginary world he himself has created.

Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926–1938 is on view at New York’s Museum of Modern Art through January 12.