The warring life of the Northern Plains tribes that resisted white invasion in the 1860s is the subject of A Lakota War Book from the Little Bighorn: The Pictographic “Autobiography of Half Moon.” The book is a collection of seventy-seven Lakota and Cheyenne drawings, accompanied by extensive analysis and commentary by the social anthropologist Castle McLaughlin. It will be published next year by the Peabody Museum Press as part of Harvard’s Houghton Library Publication series, named for the library where the drawings were stored but little noticed for eighty years. What sets these drawings apart from others of their kind is the persuasive argument made by McLaughlin that most of the drawings, and the book as a whole, represent an Indian account of episodes during the conflict known as “Red Cloud’s War” (1866–1868), and that it may be possible to identify three of the artists.

“Ledger art” is the term given to the large body of colored drawings by Plains Indian artists of the generation that came of age in the 1850s and 1860s, fought in the Indian wars of the 1860s and 1870s, and survived into the 1920s and 1930s. Most of the drawings were made on paper taken from ledger books found at military and trading posts or taken from soldiers and civilians killed in the fighting that ended as the buffalo-hunting tribes were confined to reservations by 1880. Originally drawn by Native Americans as a personal record, many hundreds of these ledger drawings passed into the hands of government officials, military officers and ordinary tourists who thought of and displayed them as “curios” for a time, then stored them away in attic trunks. Beginning in the 1950s, when the actor Vincent Price obtained a now-famous ledger book in La Jolla, California, ledger drawings began to be appreciated as art, first, and later for what they revealed about Plains Indian culture, religion and society. But the artists themselves clearly intended their drawings to record personal hunting and military exploits, and Castle McLaughlin now argues that they were also intended to record history, including known episodes from Red Cloud’s War.

McLaughlin identifies six artists, largely from the distinctive style of each in portraying details of horse and human anatomy—noses of men and the feet of horses, for example. The history of Red Cloud’s War, recorded in military reports, newspaper accounts and later interviews of Lakota and Cheyenne participants, allows McLaughlin to push identifications an important step further—to known individuals. Artist B, she suggests, is the Minneconjou war leader High Backbone, killed in a fight with Shoshone in 1870. Artist E was a man named Thunder Hawk (pretty clearly identified by his name glyph—a drawing of a hawk with a “voice line”). And Artist D, shown killing two soldiers, an officer and a sergeant, may have been the famous Oglala war leader, Crazy Horse. The double killing occurred in December 1866, and some Indian sources say the killer was indeed Crazy Horse, who can be tentatively further indentified by his yellow body paint and the lightning streaks down his horse’s legs, a design chosen by “thunder dreamers” of which Crazy Horse was known to be one.

Although McLaughlin’s arguments on these and other matters cannot be called proved, they are persuasive and plausible. What is perhaps most remarkable is the intensely personal style of each artist, and the attention to identifying detail of weapons, clothing and body paint, thereby allowing the viewer a glimpse of the war from the other side.

A Lakota War Book from the Little Bighorn, Peabody Museum Press

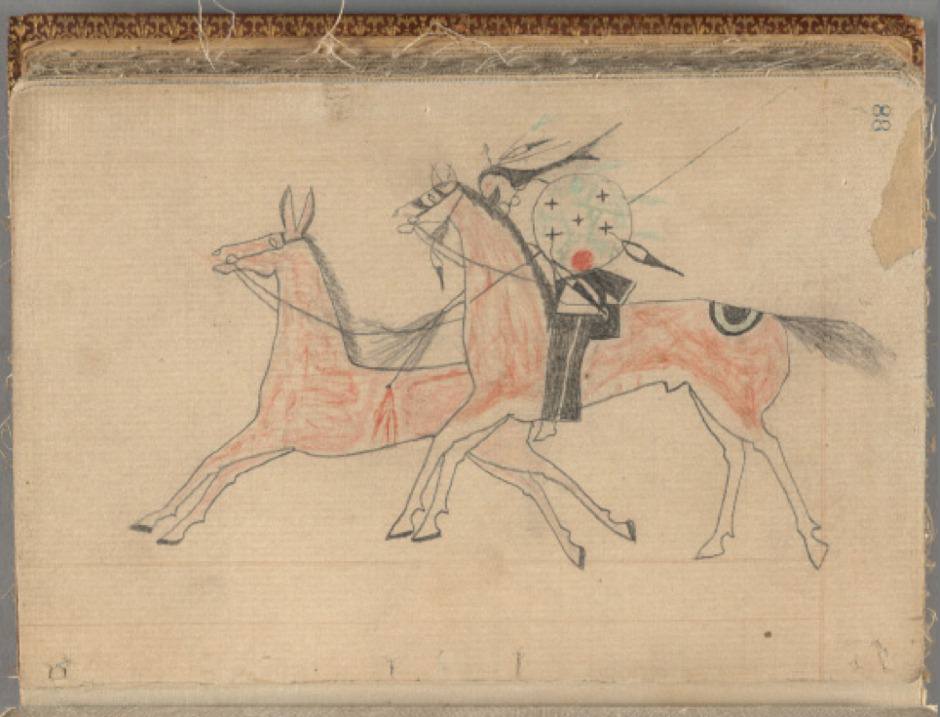

Artist D (possibly Crazy Horse): A warrior on thunder horse attacks an officer and soldier in the cavalry, similar to an ambush of a small detachment from Fort Phil Kearny in December 1866. An early owner of the ledger book believed that the shield design suggested its owner was named Big Turtle—a probable misreading. Images on shields conferred power, and were not intended as name glyphs.

A Lakota War Book from the Little Bighorn, Peabody Museum Press

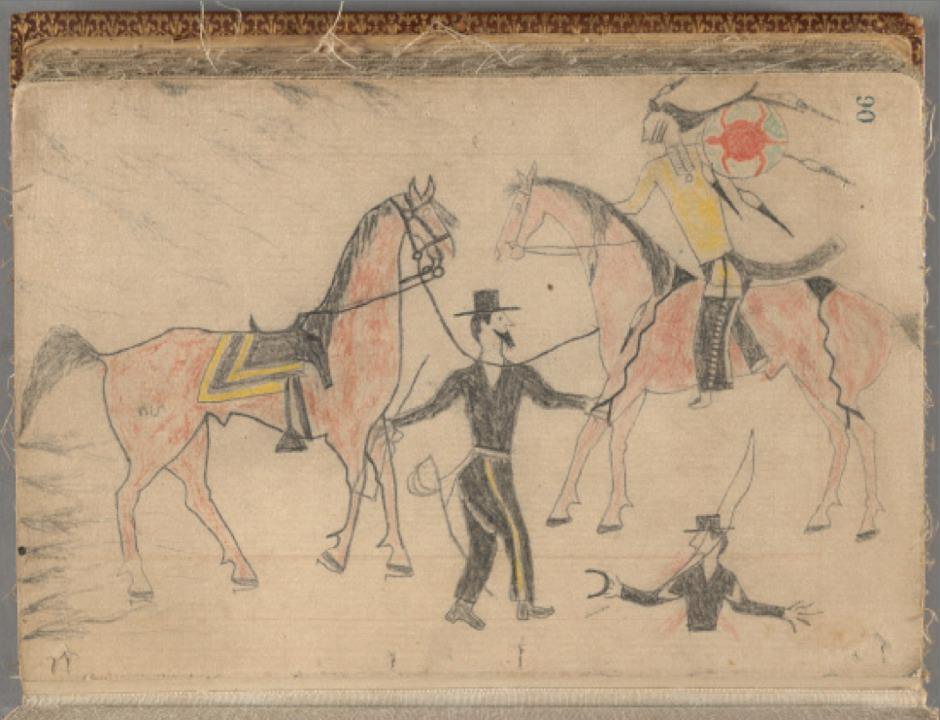

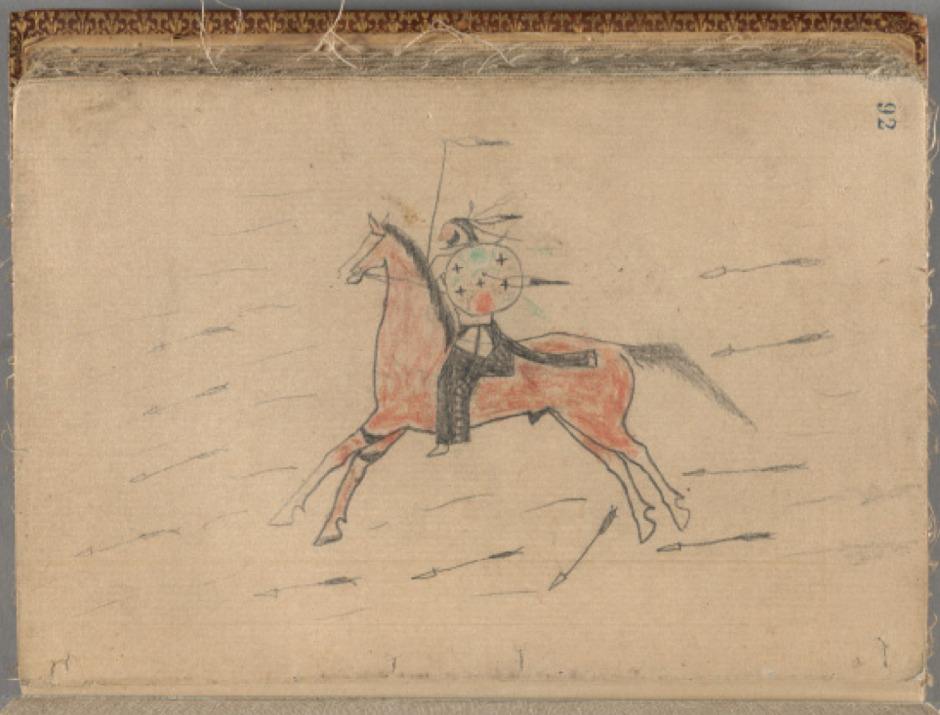

Artist D (possibly Crazy Horse): A mounted warrior with a shield decorated with crosses that may represent stars or perhaps dragonflies, thus giving the power of rapid movement to man and horse. The arrows filling the air suggest a fight with a rival tribe.

A Lakota War Book from the Little Bighorn, Peabody Museum Press

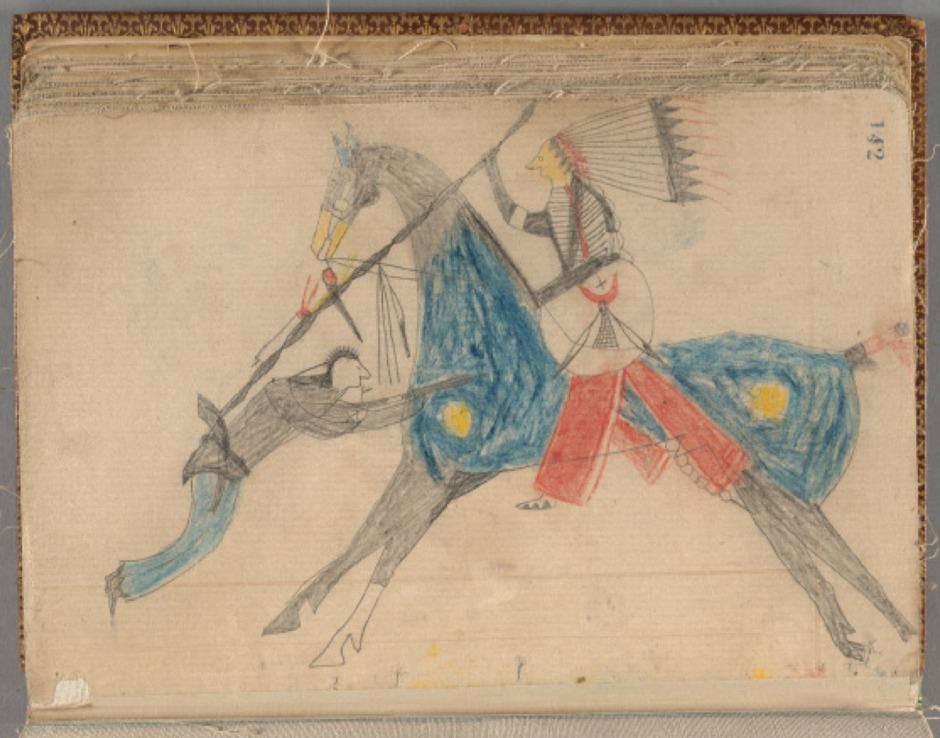

Artist B (possibly High Backbone): A warrior mounted on a blue roan horse kills a Native American Army scout, probably a Pawnee, something High Backbone is reported to have done in 1865. Tied to his lance is a pipe stem, sign the bearer was a blotahunka or war leader.

A Lakota War Book from the Little Bighorn, Peabody Museum Press

Artist E (possibly Thunder Hawk): A warrior on foot attacks a white civilian armed with a revolver. Note the wiggly “voice” lines extending up and out from the bird linked by a separate line to the warrior’s head, almost certainly a name glyph for Thunder Hawk, the name of several warriors known or presumed to have been active during Red Cloud’s War.

A Lakota War Book from the Little Bighorn: The Pictographic “Autobiography of Half Moon” by Castle McLaughlin is published by Peabody Museum Press. The original manuscript, MS Am 2337, can be found in the collections of the Houghton Library at Harvard University. Gift of Mrs. Harriet J. Bradbury, 1930.