The *riddle* does not exist…

The solution of the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of the problem.

These famous lines from near the end of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus have never seemed more wishful and sad than upon seeing the haunted likenesses of his contemporaries in the exhibition Facing the Modern: The Portrait in Vienna 1900. Like Wittgenstein, the men and women on view long for liberation and enlightenment, and do so precisely because they are entrapped by isolation, anger, and confusion. For the people in these pictures, the riddle surely does exist—it is omnipresent and inescapable—and the problem of life has no solution.

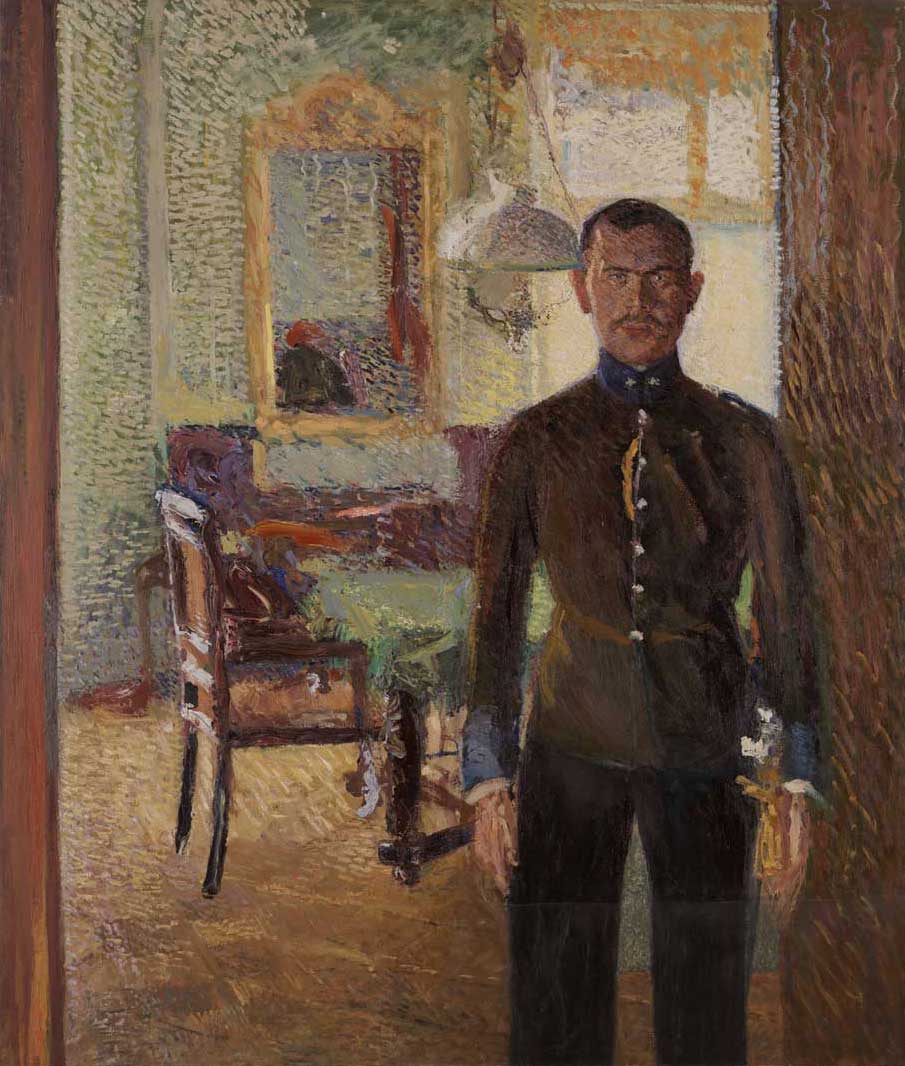

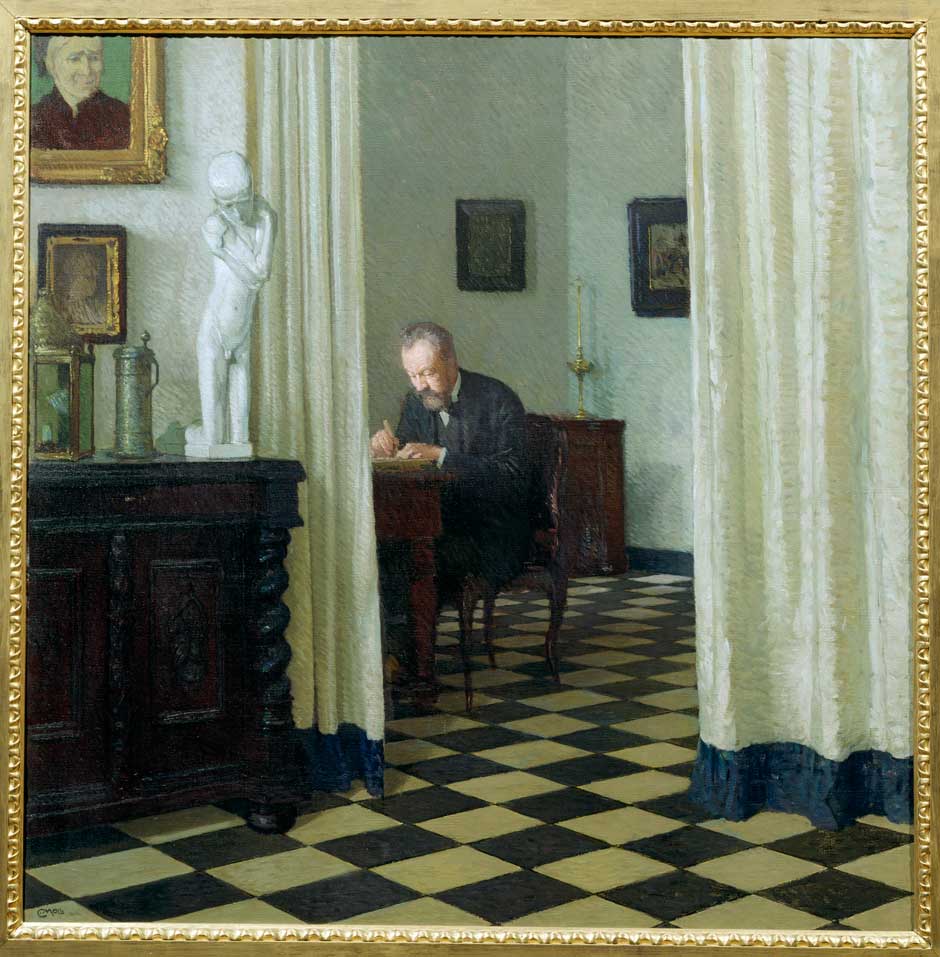

This poignant show, on exhibit at the National Gallery, London until January 12, 2014, is far from a celebratory survey of the art of the city in the age of Klimt, Schiele, and Kokoschka. Rather, as the catalog states, by featuring many lesser-known figures, such as Richard Gerstl and Carl Moll, and by selecting works according to a limited set of essential themes, the show’s curators attempt to create “a portrait of Vienna itself.” This is impossible to do in full, in view of the complexity and contradictions of life in the city one hundred years ago. Yet the show nevertheless offers a strong sense of the melancholy, the introspection, and the desperation that were characteristic of Vienna in that era.

Vienna around 1900 has attracted immense attention since Carl Schorske’s great book on the cultural life of the city was published in 1981, and the subject now draws a wider audience than ever before, owing in part to the efforts of the Neue Galerie in New York and the recent avalanche of books and exhibitions. One sign of its prestige is the eight- and nine-figure sums paid for paintings by Klimt, among the highest ever for a work of art. Yet while many of these shows and publications recognize the tension and struggle in Vienna in the early years of the twentieth century, there has been a tendency to glorify the outpouring of artistic and intellectual creativity and to romanticize or minimize the psychic pain and the corrosive social setting that spurred it.

Vienna was not only a birthplace of modernism; it was also a “laboratory of world destruction,” to quote the legendary Viennese journalist Karl Kraus. The show at the National Gallery helps the viewer to see in the clearest terms the suffocating anxiety and oppressive solitude of the artists, writers, and patrons who were responsible for much of Viennese modernism. The Austrian novelist Hermann Broch famously called Vienna the city of “joyful apocalypse.” In this show, you can almost watch the apocalypse unfold.

The first room of the exhibition is dedicated to recreating a show on Viennese portraiture of the early nineteenth century that was held at the Galerie Miethke in 1905. Neither the catalog nor the wall texts clearly explain why the exhibition begins in this manner, an omission that has caused considerable misunderstanding and criticism in the British art press. The Galerie Miethke was perhaps the most progressive gallery in Vienna at the time, yet the 1905 show was intended to demonstrate the technical command and expressive power of Austrian painting in the Biedermeier period, nearly one hundred years before.

The show was masterminded by Moll, a member of the Secession movement who was Mahler’s future stepfather-in-law and a good friend of Klimt and Kokoschka; furthermore, it was championed by the writer Berta Zuckerkandl, whose salon in her apartment designed by Josef Hoffmann and Dagobert Peche was a center of intellectual life in the city. Just as Mahler turned to the poetry of Rückert from the 1830s to provide texts for some of his most emotionally powerful music, so Moll and others looked back to the penetrating veracity of Biedermeier portraiture to find a model for their own experiments in the scrutiny of self and sentiment. The pictures in this room, by painters little known outside of Austria such as Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller and Friedrich von Amerling, have a startling frankness of psychological revelation.

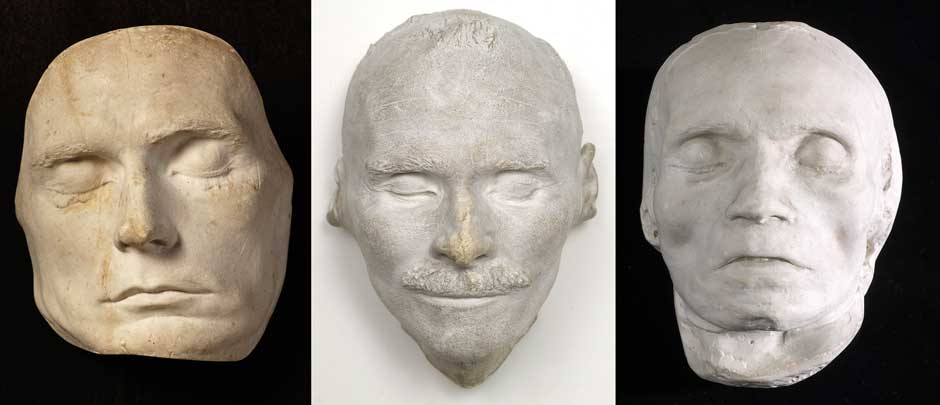

The mournfulness of many of these images clearly appealed to Viennese artists of the early twentieth century. The first items in the show are Beethoven’s death mask and a post mortem painting of his hands turning grey and blue, and among other pictures in the room is von Amerling’s painting of his wife on her death bed (1843). Even the one seemingly triumphant picture here, von Amerling’s large and resplendent portrait of Cäcilie Freiin von Eskeles (1832), although depicting her dressed in luxurious clothing and posed in front of a red velvet curtain like a Baroque princess, emphasizes the keen sorrow of her gaze. Despite her wealth and status, like nearly everyone else in the room, she is shown alone with her sad thoughts. The theme of painful solitude was everywhere in the culture of the city at the time. Indeed, the catalog of the 1905 exhibition spoke of today’s “isolating times”; and just two years later in his book, Vienna, Herman Bahr, referring both to artists of the past such as Beethoven and Waldmüller, and of the present such as Mahler and Klimt, wrote, “Real people are always kept in a cage of immense loneliness [in Vienna].”

Advertisement

In the city that inspired The Man Without Qualities and The Woman Without a Shadow, portraiture too often depicted figures in a state of dematerialization or unreality, in which the dead and the dying, dreams and ghosts predominate. In the London show, this becomes evident the moment you enter the rooms of portraits from the early twentieth century. For instance, to your right in the first of these galleries is Gerstl’s picture of The Sisters Karoline and Pauline Fey from 1905, which depicts the two young women floating in their ethereal white gowns like bodiless phantoms. The air of the uncanny is made all the stronger by their gigantic black eyes which glow like the eyes of an idol.

The Viennese playwright and poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal wrote, “We have, as it were, no roots in life and wander around like clairvoyant shades who are yet blind to the daylight.” As if to capture the character of this ghostly existence, in picture after picture, such as Kokoschka’s Count Verona and Klimt’s Posthumous Portrait of Ria Munk III, almost nothing is represented in a natural manner. Instead, space and setting are flattened or eliminated and proportion and anatomy are distorted and exaggerated, thereby intensifying the effect of morbid ill-ease.

The most powerful image of dematerialization in the entire show is Egon Schiele’s haunting picture of his wife Edith, expiring from the Spanish Flu. Drawn in loose lingering lines of charcoal, she is turning to wisps of smoke right in front of you. Only her sad and penetrating eyes remain fixed in the slowly spinning cloud of disappearance. Schiele himself died of the flu three days later, on October 31, 1918—Halloween—the same day that the Austro-Hungarian Empire was dissolved. Halloween is an apt terminus of the show, for in a sense the entire exhibition is a danse macabre that begins with the Funeral March of Beethoven’s Third Symphony and ends with Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder. The somber music reaches its devastating climax in a gallery that includes not only Schiele’s image of his wife, but also Klimt’s drawing of his dead infant, and a posthumous portrait by Gyula Benczur of the beautiful but insane Empress Elisabeth, who was assassinated by an anarchist in 1898.

In Vienna your every act could provoke a paroxysm of ecstasy or rage. At the end of a performance of his Gurrelieder, Arnold Schoenberg received a standing ovation for a quarter of an hour; at the end of a performance of his Pierrot Lunaire, a member of the audience shouted, “Shoot him! Shoot him!” The endless conflict, the extreme isolation, and the intense claustrophobia drove many artists and musicians away from Vienna. Klimt said to Berta Zuckerkandl in 1905, “I want to get out,” although he in fact decided to stay. Mahler left for New York in 1907, Schoenberg went to Berlin in 1912. As Hofmannsthal wrote, “We must take leave of the world before it collapses.”

Many of those depicted in the show who did not leave Vienna were later destroyed by the conflagration of world war that arose from this city. Carl Moll became a fascist, and committed suicide in 1945. Amalie Zuckerkandl, the subject of the last picture in the show—a portrait left unfinished by Klimt at his death—was the sister-in-law of Berta Zuckerkandl; she was murdered by the Nazis in a concentration camp in 1942. Her intelligent, glittering, bewildered eyes gaze out of her face, asking us to remember and to understand.

“Facing the Modern: The Portrait in Vienna 1900,” is on view at the National Gallery in London through January 12, 2014.