Inside Llewyn Davis, Joel and Ethan Coen’s sixteenth feature film, depicts a week or so in the life of its titular character, a Greenwich Village folksinger. It is set in 1961, a transitional year. For roughly a decade, the singing and playing on acoustic instruments of old blues and country songs by mostly white, mostly well-educated young people had been a non-remunerative coterie pursuit in the bohemian enclaves of a few American cities. But that year, the so-called Folk Riot occurred in Washington Square Park, the fledgling Bob Dylan had just hit town, and what the folksinger and labor organizer Utah Phillips called “The Great Folk Scare” was right around the corner. This scholarly, impassioned, impoverished, rather left-wing phenomenon was, somewhat improbably, about to be translated into the realm of showbiz.

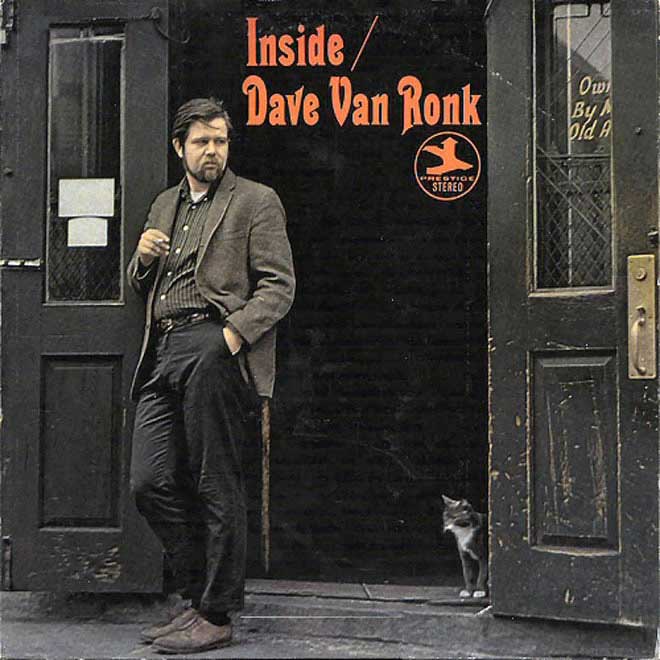

The Coen brothers are nonpareil pastiche artists, capable of burrowing deeply enough into the cultural gestalt of particular moments of twentieth-century America to render a facsimile that feels right without being slavish, to riff on aspects of a setting without being shackled to the historical record, even to concoct convincing if outright fakeries, such as the 1930s wrestling-movie genre they invented for Barton Fink (1991). Their plundering of the folk milieu here has inspired various searches for à clef equivalences by online hobbyists, although nothing is as exact as all that. Inside Llewyn Davis owes quite a lot to the Greenwich Village folk singer Dave Van Ronk, beginning with its title, which is also the title of a record pictured in the movie with a cover nearly identical to that of Inside Dave Van Ronk (1963).

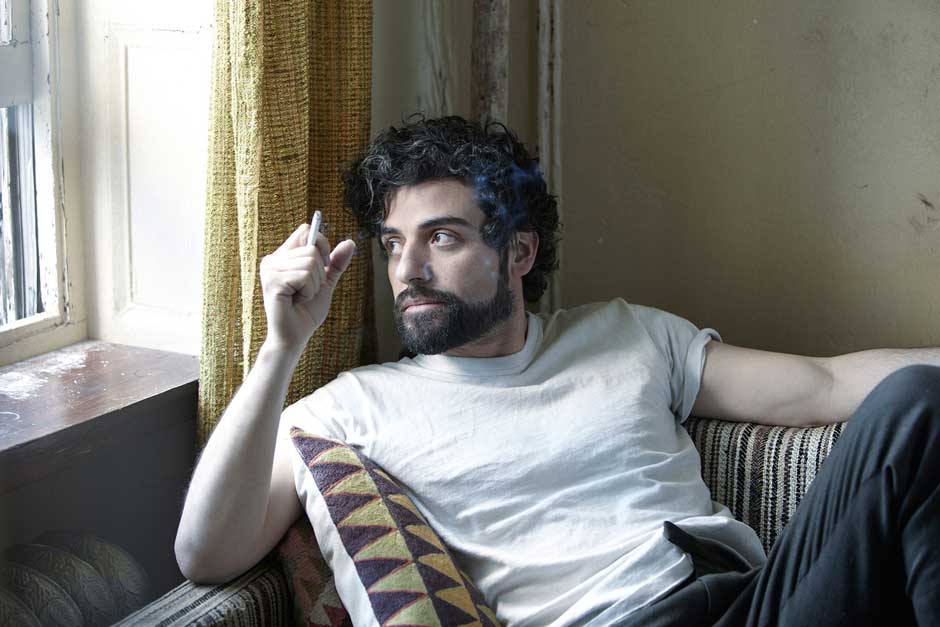

The movie extensively mines Van Ronk’s remarkable posthumous memoir The Mayor of MacDougal Street (seamlessly compiled from interviews by Elijah Wald; Da Capo, 2005) for scenes, anecdotes, and details of background, and its protagonist, Llewyn Davis (played by Oscar Isaac) sings songs closely associated with Van Ronk. He is, however, emphatically not Van Ronk, any more than the singing married couple named Jim and Jean (Justin Timberlake and Carey Mulligan) are meant to portray the historical Jim (Glover) and Jean (Ray)—who let Phil Ochs sleep on their couch, not him. Van Ronk was gregarious, good-humored, politically active, learned, and grounded, traits that could not be farther from Davis’s character.

Similarly, the film’s Troy Nelson (Stark Sands) shares a song and an Army stint with the pioneering singer-songwriter Tom Paxton, Al Cody (Adam Driver) a cowboy persona and a New York Jewish background with the singer and Woody Guthrie associate Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Bud Grossman (F. Murray Abraham) a last name and a place of employment with the manager and folk impresario Albert Grossman—actually, he pretty much is Grossman, minus the visuals. But the Coens have not cut and shuffled the deck to thinly disguise gossip (nor in the interest of satire, unlike Christopher Guest’s knowing 2003 folk-scene send-up A Mighty Wind). Instead their confection buttresses with convincingly half-familiar details what is in essence a character study.

Llewyn Davis is, like Van Ronk, a working-class kid from Queens who has made his way to the Village’s bars and basket houses (cafés where a basket was passed for tips), driven by his love for those often strange, often ancient songs that people in New York City had up until then mostly ignored. He had a partner with whom he recorded an album, but who jumped off the George Washington Bridge (“It’s traditional to jump off the Brooklyn Bridge,” another character observes). The partner’s bereft parents try to be parents to Llewyn, but he exploits this, joylessly, only when he is desperate for a meal and a doss.

Llewyn may be something of a shit, but mostly he’s young and feckless, with zero thought for the future. He is constantly imposing on his friends, impregnating his one-night stands, leaving people in the lurch, saying the wrong thing at the wrong time. He lives nomadically from couch to couch, his sole possessions his guitar and a battered shoulder bag—he has more clothes than you’d expect, and in better shape, but hey, it’s a movie. He tries to extract money from the head of his record company, Mel Novikoff (Jerry Grayson)—a stand-in for Moe Asch of Folkways—but is easily outmaneuvered by the old fox.

His efforts at self-promotion are undermined by self-sabotage; he will, for example, undertake a grueling midwinter trip to Chicago by thumb for an audition, only to flub his chances when he gets there because he is unable to tailor his self-presentation to the circumstances. His seaman’s papers are his ace in the hole—like many a working-class bohemian of the time he ships out when money gets tight—but actually using them entails knowing where they are, which is beyond his managerial capabilities. Still, he is sufficiently responsible that he spends the better part of the movie uncomfortably carrying around someone else’s squirming cat, for which he feels no particular affection.

Advertisement

But everything changes when he performs. Oscar Isaac sings and plays six entire songs in the course of the movie, and apparently played them through numerous retakes with no lip-synching and no click track. The arrangements, at least of “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me,” “Green Green Rocky Road,” “Dink’s Song,” and “Cocaine,” are essentially Van Ronk’s, but Isaac is engaged and believable in addition to being skilled. The impression is that of a young man who has a great many more mistakes to make in life before he wises up, if indeed such a thing is ever to happen, but who channels the accrued wisdom of the ages when he enters the folk-lyric continuum, becoming an entirely different person. This suggests a description not so much of Van Ronk—or Paxton, or Ochs, or Elliott—as of the man who upset the apple cart: Bob Dylan. Indeed, the young Bob makes a fleeting cameo appearance near the end—while he is impersonated by Benjamin Pike, that’s Dylan himself on the soundtrack, singing his early song “Farewell.”

But then there’s the subliminal hint given by Llewyn’s Welsh name, in addition to his blank-slate personality. Maybe the Coens really wanted to make an early-Dylan biopic but couldn’t—it would probably be impossible, at least right now, for a variety of reasons—and front-loaded the picture with Van Ronkiana to blur the traces. And perhaps it is this matter of cross purposes that leaves the movie feeling aimless. The story is no more than a rambling anecdote, Llewyn’s character undergoes no change for all that he experiences and endures, and to the extent that the picture has a structure at all, it is a half-hearted and inexplicable loop—the beginning, in which he is unaccountably cold-cocked by a man in a large hat in an alley outside a club, foretells the end for no very good reason.

Then again, it could be said that historical fiction, like science fiction, is really always about the present. Llewyn Davis is a creature of the here and now, not of 1961. He has none of the communitarian goodwill, the erudite passion, or the optimistic idealism that marked the period. He is a confused, irascible striver who isn’t sure what he is striving for, apparently seeking a career when folk music was about the last place you’d look for one. It is suggested that he has been flopping on friends’ floors for months, when, at the time, people generally only did that when they first hit town, since it wasn’t hard to scratch up the twenty or thirty bucks a month it took to rent a tenement flat fifty years ago.

But if you excise the period details, he makes sense. Whereas in a better time he would spend five or ten years woodshedding and developing a soul, he has no choice but to enter some kind of race right away or die on the vine. He is consistently crass because he feels threatened by people and ideas he can’t dominate—and he can’t dominate very much because he feels threatened. (How else to explain his heckling an Appalachian singer, complete with autoharp and authentically awkward?) Somehow he has made a connection to something that is genuine and profound—the haunting music—but circumstances force him to treat it as a card to play rather than as a path to explore. The implacable dictates of a society in which the value of everything is determined solely by its sale price will sooner or later shuttle him into some low-level desk job. He’ll take his guitar out on weekends for a while, but then the regret will become too strong and he’ll bury it in the back of his closet. And when he sees this movie, he’ll feel a pang—and then he’ll laugh about the vanity of youth.