In all the comment about this month’s Sochi Olympics, there is bewilderment above all about Sochi itself: Why on earth would the Kremlin decide to host the Games in an underdeveloped place where terrorists lurk nearby—a place that a front-page New York Times story this week describes as “the edge of a war zone”?

The answer is not as complicated as it may seem. Vladimir Putin comes from St. Petersburg. He rules from Moscow. But it is the North Caucasus that launched him on his path to the summit of Russian power. Anyone who wants to understand the many controversies now roiling around Sochi must start with this fundamental political fact.

Russia launched its Olympic bid in 2006, a moment when Putin was basking in his hard-won status as the leader who had finally vanquished the long-running rebellion in Chechnya. Putin did not choose Sochi by chance. He believed that presiding over an Olympic miracle in the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains, not far from places that had been battlefields a few years before, would cement his triumph over historical enemies.

The Chechens began their struggle for independence from Moscow in 1994, staving off full-scale attacks by Russian troops for the next two years. A peace treaty was finally declared in 1996, essentially granting the Chechens full autonomy over their shattered republic. Then-President Boris Yeltsin never quite recovered from the setback. From that point on, the Russian army’s haphazard performance in the Chechen campaign fused seamlessly, in the minds of many Russians, with Yeltsin’s own shambolic performance as president.

Putin, the former secret police chief who rose to the post of prime minister in Yeltsin’s waning days, understood that reversing this humiliation was the key to his own political ambitions. He soon got his chance. In August 1999, Chechen guerillas staged a raid into a neighboring republic in an apparent effort to widen their separatist revolt into a broader Islamist insurgency. A few weeks later a series of terrorist bombings in Moscow and other cities, also attributed to the Chechens (though some of them have been linked to the Russian security services themselves), prompted a national outcry. Putin responded by sending the army back into Chechnya with a ferocious determination that sealed his claim to the presidency. He gave the army and the FSB a free hand, and Westerners were abashed by his notorious vow that “we’ll hunt them [the terrorists] down and kill them, even if they’re in the toilet.” Russians, by contrast, exulted in his swagger.

By 2005, the insurgency was effectively quashed. Its self-declared leader, Aslan Maskhadov, had been killed in an operation that had all the characteristics of an FSB hit. Installing Moscow-friendly Chechens in positions of power in the new local government, Putin now began to pour enormous amounts of cash into rebuilding the ruined republic. (While many reports on the Sochi Games have focused on their staggering cost, owing in part to extensive corruption, few have noted the precedent: Putin’s gigantically wasteful yet undeniably effective stimulus plan for the reconstruction of Grozny, the Chechen capital.) Many war-weary Chechens were happy to embrace the new status quo, even when it meant accepting the establishment of a capricious new police state. A few guerillas soldiered on, but gradually many of them laid down their arms, while others emigrated to join jihadi struggles elsewhere in the world.

Enter the Olympics. Throughout the life of the modern Olympic movement, hosting the Games has offered a powerful form of national rehabilitation to countries that have ended up on the wrong side of history. In 1964, Japan used the first postwar Olympic Games on its soil to showcase its new openness and its economic development less than two decades after its rise from the destruction of World War II. In 1972, the West Germans tried to use their staging of the Munich Games to comparable effect, only to find it marred by the horrible irony of a massacre of Jewish athletes. The organizers of the 2008 Beijing Olympics went far beyond these predecessors in their efforts to present the image of a new society that had, by all appearances, effortlessly forgotten the genocidal ferocity of the very same Chinese Communist Party that was now organizing the world’s highest-profile sporting event.

Putin’s bid to bring the Olympics to Russia follows a similar pattern. In an interview published just a few days ago, Putin explicitly links the Games to the humiliations of the recent past: “There is also a certain moral aspect here and there is no need to be ashamed of it,” he said. “After the collapse of the Soviet Union, after the dark and, let us be honest, bloody events in the Caucasus, the society had a negative and pessimistic attitude.” The Olympics, he explains, are a necessary part of an effort to “strengthen the morale of the nation.” Putin and other Russian officials have also suggested that the massive infrastructure developments at Sochi are merely the prelude of a general push to develop tourism throughout the North Caucasus, currently the poorest region in Russia. In this respect, Sochi is an integral part of the Kremlin’s counterterrorism strategy, which aims to salve discontent by jump-starting the local economy. One is inclined to be skeptical that this approach can work.

Advertisement

Along with their location, the Sochi Games are symbolic for their date: the Olympics will end on February 23, the exact day seventy years ago when Joseph Stalin deported the entire population of the Chechens from their homes to forbidding locations in the Far East and Siberia, resulting in the deaths of tens, perhaps hundreds of thousands. Two years ago, the current president of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, quietly changed the official date for commemorating the deportation from February 23 to May 10—in part, perhaps, to divert attention from the coincidence.

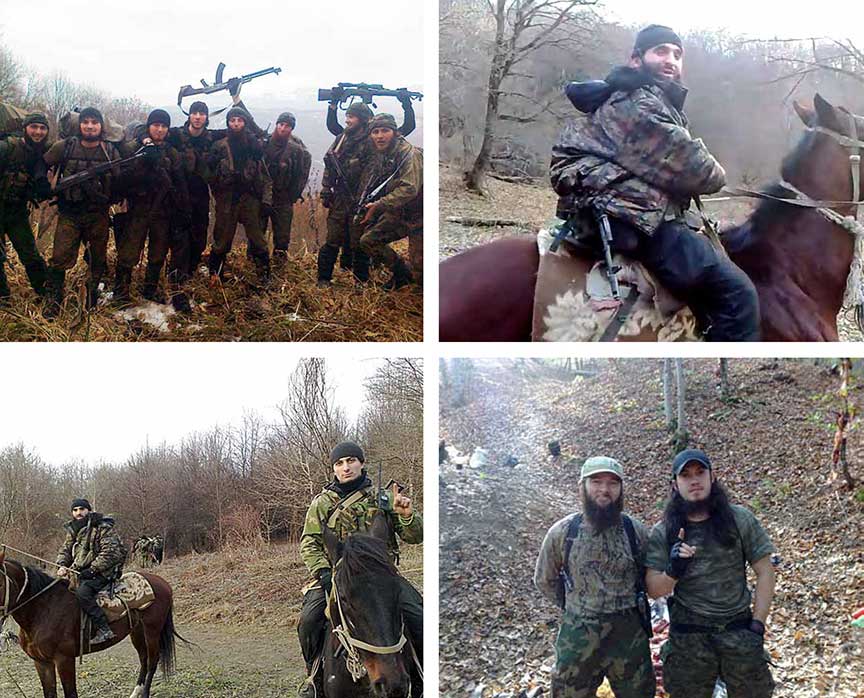

Much of this background to the Sochi Olympics is recounted by the photographer Rob Hornstra and the journalist Arnold van Bruggen in The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus. Their lavishly illustrated book, the product of five years of frequent reporting trips to Sochi and its neighboring territories, conveys the texture of this impossibly multilayered region more powerfully than any other I’ve seen. Not only have they captured the utopian elan of the new Grozny and the grandiosely disruptive projects of the Games themselves, but they have also picked up the wayward details of holidays past, everyday cuisine, personal biographies, forgotten tragedies. They offer portraits of farmers, dreamers, strip club owners, mullahs, guerilla fighters, young Cossacks in T-shirts, people displaced by war and local feuds and mammoth construction projects.

The authors succeed—despite their occasional problems with unraveling the tortuous local history—in communicating the deep historical tragedies that resonate into the present in so many unpredictable ways:

If the Games are successful, one anticipated byproduct is that this would help reclaim Russia’s place on the world stage and make the so-called “humiliation of the 1990s,” when the Soviet Union collapsed and Russia lost its status as a world power, a thing of the past. But the story of modern, prosperous Russia is set against a backdrop of contrasts: poverty, refugees, violence, and human rights violations. There are countless stories to be told.

The latest events remind us, in short, that it is not so easy to escape the hamster wheel of the past. The insurgency that Putin thought he had crushed has since scattered its embers around the entire region, inflaming other parts of the North Caucasus that had long remained immune. The causes have much to do with the spread of salafi and Islamist ideas among hitherto quiescent Muslim populations, fueled by the heavy-handed policies of Putin’s henchmen in the region. (The arbitrary kidnapping and extralegal detention of young men remotely suspected of ties with the insurgency has probably done more than any other single policy to drive local resentment of Moscow’s rule.)

It’s important to note that not all of the resistance is violent. Some of the most moving protests against Sochi have come from the Circassians, a people who fought bitterly against the encroachment of tsarist rule in the mid-nineteenth century. Like the others, they ultimately lost. Their leaders surrendered to the Russians at a spot near the current Olympic site of Krasnaya Polyana. Most of their people were then deported to the Ottoman Empire or massacred; hundreds of thousands are presumed to have died. While a few remain in their ancestral homeland, most Circassians today live in Turkey or the Middle East—including some 100,000 in Syria, where they have suffered hugely during the current civil war. Circassians around the world have seized upon Sochi to remind the world of what happened to them 150 years ago, and, in some cases, to demand the right of return to their lands. But they have done it largely through peaceful protests, frequently involving group performances of their elegant and melancholy traditional dances.

One can only hope that the Circassians continue to resist the temptation to take up weapons. Too many others have already succumbed. In 2003, on my way to Chechnya, I noticed a pile of flyers lying on a table in the lobby of the hotel in the resort town where I was staying. I picked one up and read the title: “Methods for Recognizing a Female Suicide Bomber.” The text offered a few observations about the women “martyrs” who were willing to transform themselves into living munitions as a way of avenging brothers or husbands who had died in the fight against the Russians. There was this, for example:

Advertisement

The reason for recruiting women: heightened receptiveness to suggestion and particular impulsiveness (the man thinks with his mind, the woman with her heart); revenge for relatives; the husband is god, tsar, and military leader in the Caucasian family, so when the man is killed, even the weaker sex is ready to take revenge for him.

I couldn’t help recalling that surreal flyer, when I heard the news, just a few days ago, that Russian security forces were urgently searching for Ruzanna Ibragimova, a twenty-two-year-old woman alleged to be planning a suicide attack on the Sochi Games. Ibragimova, unlike some of the other so-called “black widows” hunted by the Russians, was rumored to have made it through the security perimeter around Sochi and had taken up residence somewhere in the city. I earnestly hope that she doesn’t blow herself up. I hope that the Games come to an end in peace. But I also hope that the politicians—as well as the ordinary people whose often troubled lives are traced by Hornstra’s and van Bruggen’s book—will find the will to bring genuine peace to a region that still suffers from a surfeit of ghosts.

Rob Hornstra’s photographs are drawn from The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus, by Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen, which has recently been published by Aperture.