Toward the end of Palestinian director Hany Abu-Assad’s powerful new film, Omar, short-listed for the Oscar in the “best foreign language film” category, the eponymous hero (played by Adam Bakri) says to Nadia (Leem Lubany), the woman he has loved and lost: “We have all believed the unbelievable.” The impossible backdrop to their love is the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian West Bank; and indeed there is much that is unbelievable about this occupation and the reality it has created and maintained for nearly half a century.

It is hard to fathom how the Israelis themselves can stand to live with the ongoing misery and cruelty they have inflicted, and it’s not so easy to understand how the rest of the world has let them get away with it. Then there is the shadowy space of infinite suspicion and distrust that the occupation naturally breeds among those who live under or in it. Is it possible to believe that your closest friend has sold out, has betrayed you to your common enemy, has bartered your life for his (perhaps to escape an arbitrary life-sentence in prison from a military court, as in Omar’s case)? Is it possible to believe that he hasn’t?

Omar is an ordinary young man, hardly more than an adolescent. He works in a bakery making fresh pita. Scenes of excruciating torment are interspersed regularly, ironically, with images of hot bread coming out of the oven. The Separation Barrier, which mostly separates Palestinians from Palestinians, not Palestinians from Israelis, stands between him and Nadia; from time to time he climbs over it, risking his life, in order to see her. Shooting those scenes, by the way, required the permission of the Israeli authorities; typically, they issued a permit that was good only for part of the way up the Barrier, so the producer had to improvise, and an alternative top-of-the-wall was put up in Nazareth, inside Israel.

Like any young Palestinian, Omar is subject to routine harassment and humiliation by Israeli soldiers. Those who have not seen such things with their own eyes will find the relevant scene, early on in the film, instructive: Omar is stopped by soldiers while walking down the street, then forced to balance himself on a rock while they chat and laugh at him; when he protests, they break his nose. I’ve myself seen much worse incidents in the South Hebron hills, including violent arrest of innocent civilians simply trying to reach their fields or homes.

So far, everything is, one might say, normal for life in Palestine. But Omar becomes involved in the shooting of an Israeli soldier, an incident organized by Nadia’s brother and Omar’s childhood friend, Tarek. Omar didn’t kill the soldier, but he is soon arrested by the General Security Service, the Shin Bet or Shabak, which tortures him and tries to blackmail him into working for the Israelis. Even this somehow falls into the category of the normal. But Abu-Assad tightens the screws with an inventive, even poetic, twist: we follow Omar, temporarily released by his tormentors, as he tries to remain faithful to Nadia and his friends in a situation of continuously escalating, interlocking suspicions, deceit, and inevitable betrayal, both imaginary and real. It isn’t easy to watch, but it has the unmistakable, bitter flavor of truth.

On the level closest to the surface, the film shows us one of the main pillars of the occupation—the deep penetration of Palestinian society by an army of informers and secret agents who provide the information necessary for near-total control. The institutional methods and mechanisms behind this system have been honed by Israel for decades; two excellent recent books by Hillel Cohen, a historian and Arabist at the Hebrew University, describe the early history of these efforts, beginning already in the British Mandate: Army of Shadows: Palestinian Collaboration With Zionism, 1917–1948 (2008) and Good Arabs: The Israeli Security Agencies and the Israeli Arabs, 1948–1967 (2010). For decades, well-trained Israeli handlers have mastered an evolving and highly effective repertoire of psychological devices and various forms of blackmail that serve first to “turn” their captives into informers, and then to manipulate them. Life under the Occupation, with its Kafkaesque requirement of bureaucratic permits for almost anything a person might want or need to do (movement from place to place, medical treatment, visits to parents or other relatives, building an outhouse, and so on) makes any Palestinian potentially vulnerable to blackmail. That, in fact, is the meaning, also the teleology, of full control. The Israelis have not invented these methods, but they have proven to be very skilled, and unscrupulous, in using them. Among them, needless to say, is the devilish threat to harm or even destroy a loved one, a girlfriend or wife, as we see in this film.

Advertisement

Interestingly, an Israeli film that explores this same territory—Bethlehem, written by Yuval Adler and Ali Wakeed (directed by Adler) and staring the gifted polyglot musician Tsahi Halevi—was released last year and has attracted large audiences in Israel. In its depiction of the occupation, Bethlehem shows Israelis as they like to see themselves, functioning heroically, against all odds, in a dire situation that has, it would seem, been thrust upon them from the outside. What is worse, Bethlehem seems to be driven by the standard axiology of Israeli politics: set at the height of the second Intifada, with suicide bombers a constant threat, the film doesn’t even hint at the possibility that Israeli acts and decisions might have had something to do with the outburst of Palestinian violence that began in the autumn of 2000.

By contrast, Omar has depth, nuance, and a far more complex understanding of life under the occupation. Innocence and complicity are profoundly, unnervingly intertwined in the mind of a person who is struggling to physically survive, to love, and to maintain a modicum of dignity in conditions where there is no longer any hope. In a candid interview in Hebrew (an English translation is posted here), Abu-Assad has said, “The movie is more about love, friendship, and trust” than about politics. “I tried to make a film that represented my paranoid feelings over the past five to six years.” He is also, I think, interested in the particular, lonely intimacy that must mark the relations of a would-be handler and a wouldn’t-be informer.

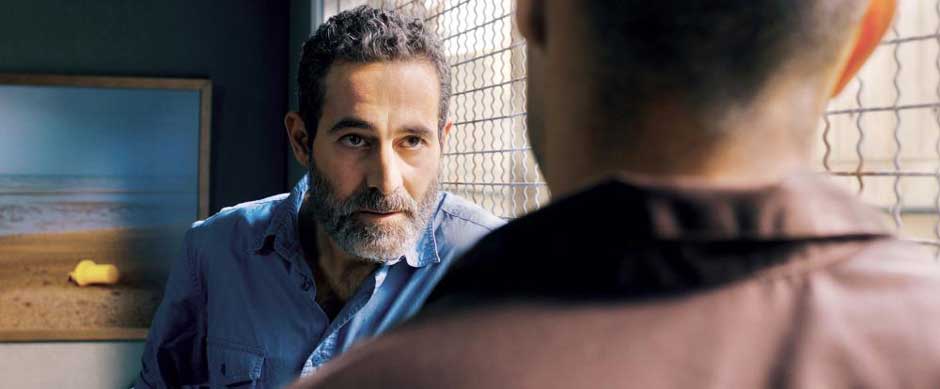

Indeed, the film smolders with sexual tension, and not only between Nadia and her trapped and driven lover. There is a moment when Rami, Omar’s Israeli handler (brilliantly played by Waleed Zuaiter), gives Omar a gun and explains to him how to use it: “The gun is like a woman. You have to treat it gently, so it will treat you gently.” These words are the oldest cliché in the modern Hebrew lexicon (though by no means limited to Hebrew); Abu-Assad uses them here in order to create a brutal, resonant irony, both overtly erotic and merciless. Like it or not, Palestinians and Israelis inhabit the same tiny, intimate space, the same ravishing landscapes they are so determined to deny to one another. Savagery is sometimes a crooked form of love.

But Omar is also a political film with its own vision that, I think, goes well beyond what Abu-Assad has himself said about the occupation. “I think,” he tells us,

that it’s the system’s elite and not the common people who are responsible. I see a great deal of difference between the two. Clearly, an ordinary soldier at the checkpoint is not innocent, he becomes part of it, but in the final analysis he is a soldier doing his duty. Sometimes it is easier for the soldier to do his duty well. Although I’m very much against injustice, Apartheid, occupation, and discrimination—it is all part of the system. A certain elite has been able to convince its people that this is the only way that we can operate, we have no choice.

It’s a generous, perhaps too generous view. The problem is that these ordinary Israelis, the “common people” who are just people, have mostly, for decades now, elected governments of the extreme right, like the present settlers’ regime run by Netanyahu. Moreover, these same ordinary people continue to demonstrate, day after day, a shocking, willful indifference to the fate of their Palestinian neighbors. Here we touch another, even more fundamental pillar of the occupation, something far more malignant and consequential than anything the Shin Bet can do.

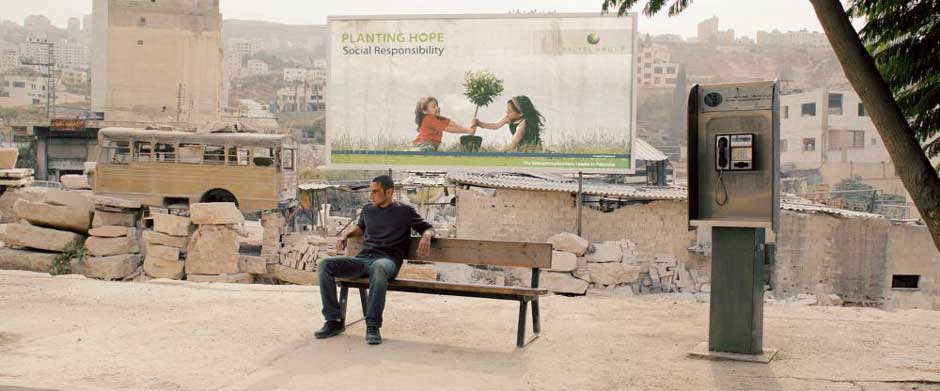

Irony is a flat, pale word for the surreal, sometimes lyrical touches that abound in this film and that inevitably cropped up in the process of its production. Scenes of unmitigated tragedy take place under billboards selling this or that, optimistically portraying happy families living normal lives. A highly convincing chase sequence, involving many people, was filmed in the refugee camp of al-Far’a, near Nablus; there are Palestinians playing Palestinians, and Palestinians playing Israeli soldiers. “We discovered,” says Abu-Assad, “that some of them loved to play the soldiers. We were quite surprised.” To internalize the subtleties, you really need to see the film a second time, listening carefully to the dialogue (or reading the subtitles) and studying Bakri’s astonishing eyes, where incipient tragedy can be plainly seen. For Israelis in particular, this is yet another film about opening one’s eyes.

Advertisement

Given the lethal reality of the occupation, the humanity of Abu-Assad’s vision is a welcome, almost therapeutic achievement. He has taken some flak from Palestinian critics for portraying Rami, the Shin Bet handler, as a real person, with wife and children—not some cut-out monster. Abu-Assad doesn’t think of such people as monsters: “Shabak agents are decent people carrying out an indecent task.” It takes courage to make such statements, even if one might be forgiven for wondering in this case what a word like “decent” might really mean. Is Rami, who is able to talk to his wife on the phone in the midst of a tortuous “conversation” with Omar, still somehow decent—or does this intrusion of the everyday world into a setting of coercion and unbearable pain make the handler even less human, more dissociated and cruel?

How many of us are, in fact, decent? What does it take to remain decent under the conditions of the occupation, on either side of the Barrier? Is it even possible? Can decency coexist with blindness? Rami speaks fluent Palestinian Arabic (Zuaiter, who plays him, is Palestinian) and is even complimented for this by his victim—but is he capable of imagining a Palestinian vision of the world? How many Israelis can do this? What hinders them? Is failure of the imagination a moral defect, perhaps the most consequential of them all? The great merit of this stark film is in forcing such questions, in all their complexity, into the private space of the individual viewer no less than into the public arena of Israel and Palestine.

Hany Abu-Assad’s Omar is now showing in select US theaters.