Does a museum show occupy space—or should it send us hurtling through it? Such is loosely the premise of two very different New York shows, the New Museum’s “Report on the Construction of a Spaceship Module” and the Studio Museum in Harlem’s “The Shadows Took Shape,” both featuring art inspired by 1960s and 1970s science fiction films.

The New Museum show takes as its central conceit the 1963 Czech film Ikarie XB-1 (released in the US dubbed and recut as Voyage to the End of the Universe), a work with a deserved cult following and an evident influence on Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Mainly set on a spaceship, Ikarie XB-1 tells the story of an international crew who launched from Earth in 2163, with the mission of reaching a mysterious, sentient “White Planet,” somewhere in the backwoods of the galaxy. Opening with one space traveler’s hysterical assertion that, “Earth is gone, Earth never existed!,” it advances the subversive notion that there may be more things in the heavens than dreamt of by scientific socialism.

The screenplay was adapted from a story by the Polish science-fiction writer Stanisław Lem that has never been translated into English. Perhaps because Lem’s “scientific” anti-utopian satires were written in thinly veiled opposition to the bogus achieved utopia of Soviet communism, his work has a degree of post-Soviet nostalgia. The stakes were so much higher then; the targets that much more absurd. In any case, Lem’s distinctive mode of deadpan, splenetic humor—elaborated, for example, in the philosophical bureaucratic infighting occasioned by the discovery of an indecipherable extraterrestrial message in his 1968 novel His Master’s Voice—suffuses the New Museum exhibition. With his abstruse color-coded philosophical systems, elaborated in charts and diagrams illustrated with pictures cut out of girlie magazines, Slovakian polymath Stano Filko, the exhibition’s most prominently featured artist, seems like a character Lem might have invented.

Curated by tranzit, a shadowy European artists’ collective, “Report on the Construction of a Spaceship Module” recreates the hexagonal corridors of the spaceship in Ikarie XB-1 and fills them with works by nearly seventy artists or artist groups—most, but by no means all, from Central Europe. Names laden with diacritical marks, they are, in general, an alien crew. Only Filko and the Czech performance artist Jiří Kovanda will be familiar to New York museum audiences, having been represented in the New Museum’s epic “Ostalgia” show of 2011. The late Hungarian conceptual artist and avant-garde filmmaker Miklós Erdély is one of the few of this group to have even an underground reputation in the US.

As was supposedly the case in the Communist societies in which many of the artists were born, the concept rules. Occupying the museum’s narrow top floor, “Report” feels at once cramped and empty. Signage is notably minimal and intentionally difficult to understand. This is not what one would call a viewer-friendly show—although on one weekend visit I observed a sprinkling of families with young children, perhaps drawn by the show’s scientific, or science-fictional, themes. Their presence added to the general bafflement.

The floor is divided into three sections. The elevator opens on the “Archeology of Futures Lab” where ancient tapes of Communist-era happenings are shown or at least cited. (Is the Kosmoss “experimental disco,” located in the Workers House of Culture in Riga, gone? Did it ever really exist?) Filko has a wall-mounted tablet nearby where, donning a wall-tethered headset that brings your forehead unnaturally close to the screen, you can ponder his ruminations on the fourth dimension. The adjacent “Main Communication Room” has a single large video screen showing statements by or about the various artists. The pieces can be lengthy, as well as impenetrable, but given the comfortable seating, it would be possible, if one were inclined, to sit spaced-out for several hours—perfect entertainment for a long, long flight to the White Planet.

Physical art works are restricted to the back room “Multi-Purpose Logistic Module” where, rather than exhibited, they are stored on open shelves. The pieces suggest various types of relics, both material (rocks and rock-like things, unclassifiable specimens, paint-by-number portraits of cosmonauts) and virtual (performance documentaries of various sorts). A photograph of Walter Pinschler’s oblong “TV-Helmet (Portable Living Room)” presides over a selection of Katarina Šević’s “News From Nowhere” series—lacquered wooden tchotchkes that, suggestive of awards or citations, might have been lifted from an apparatchik’s desk—themselves beside a vertical strip of Zsuzsi Ujj’s Cabinet of Dr. Caligari self-portraits.

Advertisement

The module is a cluttered compendium of obsolete vanguards, frozen gestures, and personal collections like an assortment of Filko’s scrap-book ephemera or the cut-and-paste “U.F.O. Gallery” created by another Bratislava-based conceptualist Július Koller. Throughout, there is a fair amount of peek-a-boo placement: János Major’s delicate engraving “Sci-fi” is half hidden behind a tablet showing someone’s “Home Porn Movie.” Some of the most assertive objects are by the Austrian sculptor Heinz Frank—a group of painted stones on spindly plinths called “The Pedestal Problem in Brancusi” and a bed of bulbous aluminum forms suggesting petrified pods from outer space. (I was reminded of the returning space traveler Ijon Tichy’s vision of Earth as a burnt potato in the opening passages of Lem’s The Futurological Congress (1971), a work in which, something like true socialism, Utopia is a drug-induced mass hallucination.)

That the various works shown in “Report” are actually elements of a larger installation is suggested by the Director of Prague tranzit Vít Havránek’s catalog essay, which, among other things, riffs on the museums of the future. These include the Museum of Non-Speaking Plants, the Museum of Active Resistance, and the Gallery of Eastern European Performance: “A queue had formed in front of the building and it was unclear whether it was for the Roman Ondák performance or an authentic formation commemorating the era of “real socialism.” (Ondák, not included in “Report,” is a Slovakian art star whose “Mapping the Universe” was installed at the Museum of Modern Art in 2007.) The former East Bloc is filled with Communist theme parks—why not consign the entire vanished system to a museum of defunct vanguards?

As “Report” has Ikarie XB-1 as a cinematic referent, so The Studio Museum’s “The Shadows Took Place” is influenced in part by the eccentric independent feature Space is the Place (1974). Shot in Oakland in the early 1970s, the movie features many local citizens, as well as some humorous stereotypes from then-current Blaxploitation films. Jazz musician Sun Ra stars as himself, beamed to Earth from his home on Saturn to inform black people that “time has officially ended” and “everything you have desired on this planet and never received will be yours in outer space.” As provocatively outlandish and dead serious as it is, Space is the Place enjoyed the status of an underground manifesto: In the future, the children of abductees will learn to abduct themselves.

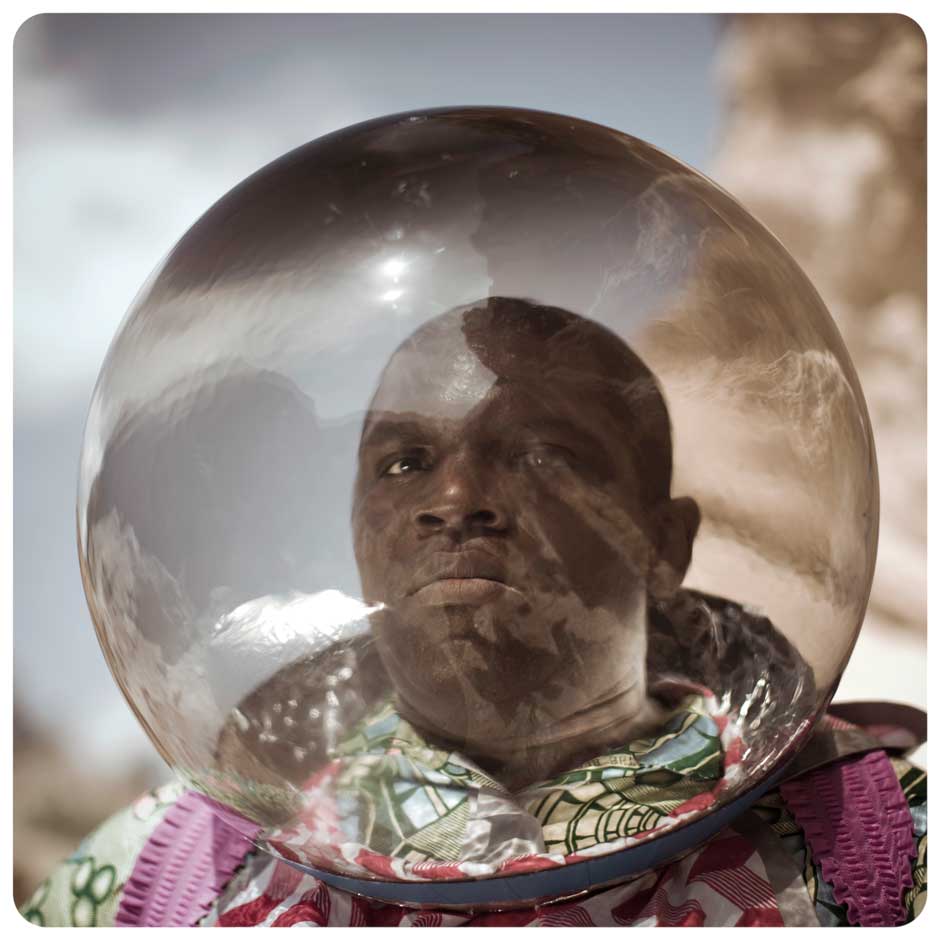

Inflected by the Sun Ra aesthetic, “The Shadows Took Shape” features several spacecrafts, including Kiluanji Kia Henda’s invented “Icarus 13”—photo-documented, using real Angolan sites, on a fictitious solar voyage. A parallel series of photographs by Cristina de Middel reimagines the actual 1964 Zambian space program. Say what?

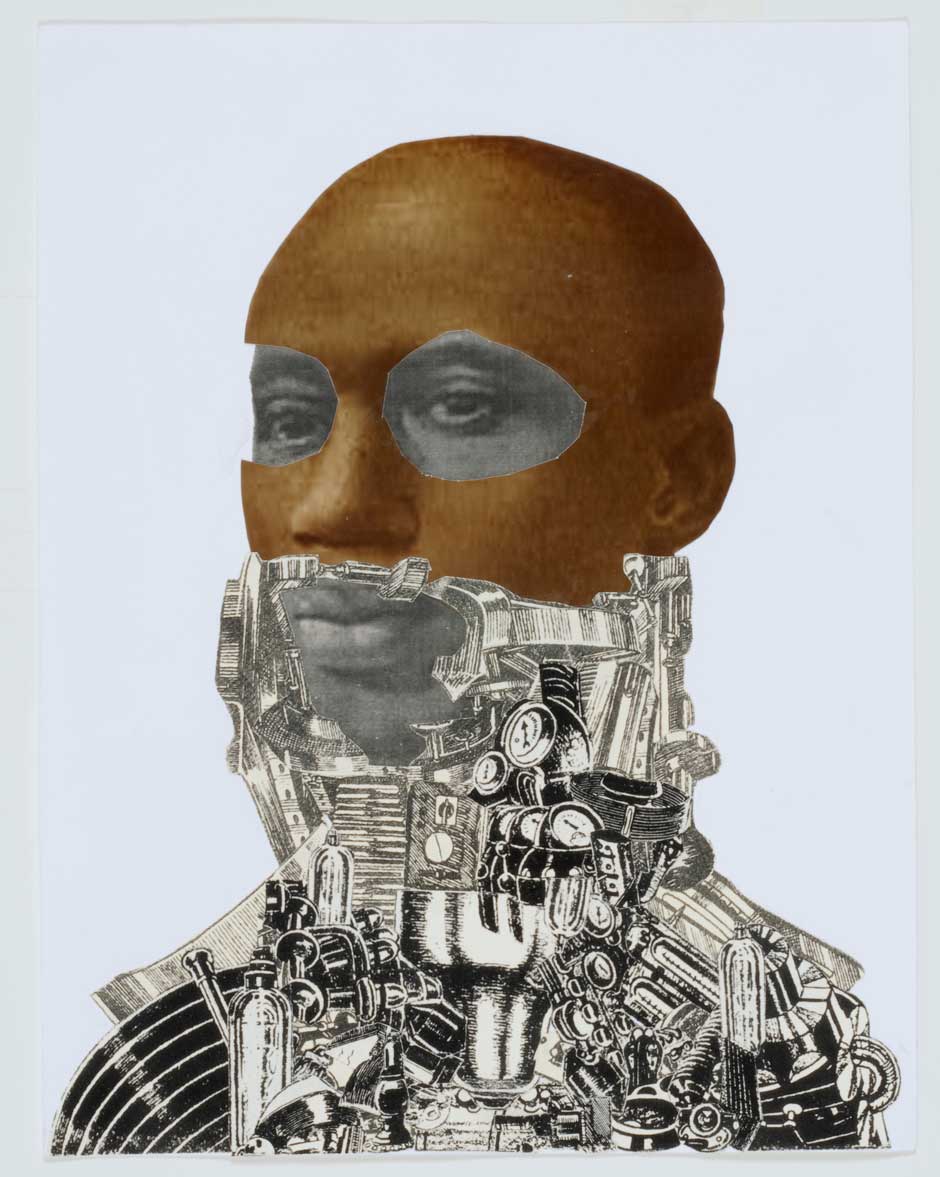

Where the New Museum’s “Report” is disorienting, “The Shadows Took Shape”—which takes its title from a composition by Sun Ra—is expansive and re-orienting. Consisting of sixty or so artworks, the show juxtaposes Sun Ra’s drawings from the 1950s and ‘60s with material from recent years—paintings and sculptures, as well as photographic, video, and mixed media work by artists from the US, Africa, Europe, and the Middle East. New genealogies and origin myths proliferate. Ancient Egypt past melds with an extraterrestrial future. Sculpture tends to be wearable; cyborgs abound, including a metallic, abstract bust of Richard Pryor (actually a monumentalized prop from the Hollywood version of The Wiz) as do weird fusions: Khaled Hafez’s animated video On Presidents & Superheroes (2009) in which, accompanied by a techno-modified speech by Gamal Abdel Nasser, an Anubis-headed Batman wanders through contemporary Cairo.

More unabashedly utopian, or perhaps less anti-utopian, than its New Museum counterpart, “Shadows” is a manifestation of Afro-Futurism, a multi-media tendency that in addition to Sun Ra and the visual artists in the show might include science-fiction writers Samuel R. Delaney and Octavia E. Butler, funk maestro George Clinton (the album covers as well as the music), and the graffiti performance artist RAMM:ΣLL:ZΣΣ, with Jean-Michel Basquiat, Ishmael Reed, Jimi Hendrix, Public Enemy, and even the Nation of Islam providing additional points of contact. Afro-Futurism is restricted to neither African-Americans (John Sayles’s 1983 movie The Brother From Another Planet is a text) nor Americans.

Is a museum show designed to pass the time—or to propose a new temporal dimension? In a general sense, the artists of “Report on the Construction of a Spaceship Module” are still the prisoners of history, while those of “The Shadows Took Shape” are preparing to slip history’s bonds.

Advertisement

“Report on the Construction of a Spaceship Module” is on view at the New Museum through April 13. “The Shadows Took Shape” recently ran at the Studio Museum in Harlem; a catalog edited by Naima J. Keith and Zoé Whitley was published by the museum.