The phone was ringing off the hook that afternoon. A mother calling to inquire about her son who had disappeared. A father frantic about a child arrested. Journalists seeking comment about military trials and the most recent crackdown on human rights groups and activists. One girl—shrieking so loud that, despite the pandemonium around me, I could hear her voice coming through the phone handset on the other side of the room—reporting that her friend had been beaten in front of her by police and then dragged off. She didn’t know what to do.

I was in the offices of the Hisham Mubarak Law Center (HMLC), a non-profit human rights law firm in downtown Cairo. It was the summer of 2013, and the country was at yet another political impasse. Disaffection with the increasingly brutal and autocratic policies of the elected president, Mohamed Morsi, had become so wide-spread as to create a significant opposition, and the various factions vying for power had reached a stalemate. Many of the incoming calls were from people who had experienced or witnessed arbitrary detention or other abuses by state authorities in recent months. But other cases—the ones I had been researching, and had come to the Law Center to follow-up on—involved more long-term ordeals mostly related to families who had lost their primary breadwinner during the revolution: a woman with two school-aged children and pregnant with twins whose husband had been shot dead. Another, whose only working-age son had been crippled. One woman’s husband, detained during the revolution and put through military trial on charges of assault against the state, had died in jail. There was an elderly couple, living on a pittance earned by an orphaned nephew who worked the streets, parking cars, selling what he could. He had disappeared without a trace during the first weeks of revolution. Another: a man who’d been blinded by the state’s rubber bullets and couldn’t provide for his family.

These kind of predicaments—the challenge of everyday life amid the tensions and lawlessness of post-revolutionary Egypt—are one of the main themes of Iranian artist Shirin Neshat’s new series of works, “Our House Is On Fire,” which was recently shown at the Rauschenberg Foundation in New York. Comprised of a series of portraits of ordinary Egyptians overlaid with hand-written poems in miniature calligraphy—hard to see, and then, almost impossible to decipher—the images disclose, by way of mere expressions, a reality to which the Persian poems speak. In the poem that gives the exhibition its title, “A Cry,” the Iranian poet Mehdi Akhavan Sales writes:

My house is on fire, soul burning,

Ablaze in every direction.

Carpets and curtains threaded to dust.

Within the smoke of this raging fire

I sob, run to each corner

Shout, scream, yelp

With the voice of a sad howl and bitter laughter.…And the fire keeps on raging,

burning all memories, books and manuscripts,

all landscapes and views.

Putting out the fire with my blistering hands,

I pass out with its roar.

As the fire rages from yet another

direction circled in smoke.

Who will ever know as my being turns into the non

being by the sunrise.

Neshat is no stranger to upheaval and loss. She was forced into exile during the Iranian revolution, while she was studying in southern California, and as a result involuntarily separated from her family. When she returned, years later, she found her parents leading an acutely altered fraction of the life they once had; almost everything had been taken from them. It was a microcosm of the change and turmoil that revolution brought. It was, in a sense, similar to the despair that she encountered in Cairo, a place she has visited frequently over the years.

What are they to do, these Egyptians, many of them unable to go out and work themselves? For those who had lost loved ones in the uprising, how could they qualify to receive compensation from the state, which was intended to help the families of those who had been “martyred” in the revolution? Of the several thousands who have died or disappeared since 2011, only a small number have been “officially” declared martyrs. How did the government decide who was a “martyr” and who was not? When, in its view, did the “revolution” even end? (According to one government official, the “January 25 revolution” lasted only until February 11, when Mubarak resigned.) And then there was the question: If a family somehow managed to obtain the elusive “martyr” status for their dead loved one, would they actually receive the promised compensation? And if they did, once that money ran out, since it was hardly enough to last a lifetime, how would they then survive without the prospect of a decent pension or handouts from the state, without a chance at employment?

Advertisement

I’ve encountered such cases, and others like them, again and again over the past three years—at various human rights organizations, but also simply on the streets of the city. They are part of the Egyptian reality, of suffering and struggle for basic survival, that predated the uprising; in many ways it was precisely this suffering that gave such broad support to the protests that began on the morning of January 25, 2011, with its chants of “Bread, Freedom, Social Justice.” In a country of ninety million people, it has been estimated that 40 percent live below the poverty line, and a staggering 60 percent do not earn enough to cover their basic needs. Since 2011, both inflation and unemployment—longstanding national problems—have risen.

In a letter to me over the summer, reflecting on the protests that were once again gripping the country, Neshat wrote:

And then where am I? I’m in New York, blinded by the normality of everyday life, where the news from Egypt, even the graphic images of the protests, the crackdowns, and the bloodsheds in Cairo all seem so distant and unreal.

This reminds me of when Iran was undergoing its Islamic revolution in 1979. And where was I then? I was a young student living in America, involuntarily separated from family and home. Of course my only access to the torturous situation in Iran were images that followed in the aftermath of the revolution; the violent protests, the crackdowns, the arrests, the executions, and the tragic scenes of the war which broke out between Iran and Iraq, lasting eight years. From my infrequent contacts with my family in Iran, I tried to imagine their days, as they battled with an oppressive regime at home, and a vicious tyrant from abroad.

For the past few years, Neshat has been working on a film about the legendary Egyptian singer Uum Kulthoum, but she quickly became deeply engaged in the aftermath of the eighteen days that many consider the “revolution” itself. Not long before Neshat arrived in Cairo in November 2012, the twenty-two-year-old daughter of her longtime photographic collaborator, Larry Barns, unexpectedly passed away. While she already knew that she wanted to create a work that captured the human condition in Egypt, the pervasive sense of disappointment and loss she had felt on previous visits, together with Larry’s own tragedy, gave a different urgency to the idea. As she told me: “I knew at that moment, somehow, that we had to go to Cairo together, to work on this in a particular way. I thought that perhaps if Larry saw other people mourning, it might help, he could mourn too, with them. It’s important to grieve, you know, and I felt that Cairo was a place immersed in that.”

In a small studio on the third floor of Townhouse Gallery, a run-down yet dynamic space at the end of a narrow, working-class lane in a part of downtown Cairo populated by car-mechanics, Neshat invited Egyptians to come in off the streets and share their stories. There was no role-playing. No pretense. Larry shared his story too. “It was like a release,” Neshat says. “It was pure emotion, an outpour, these men and women and Larry and I. Everyone sharing. Eventually everyone would be crying, hugging.” As each encounter unfolded, Larry would take the visitor’s picture.

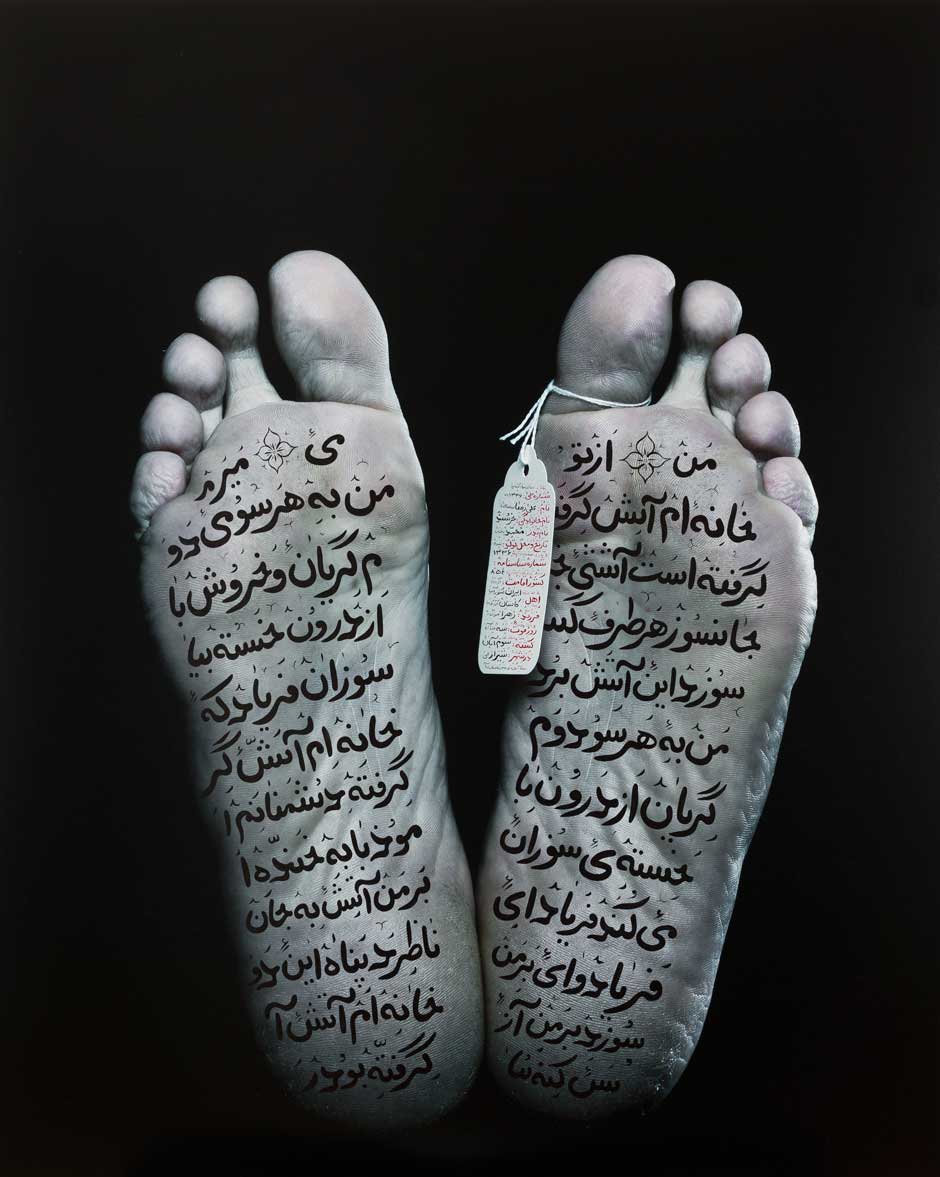

The resulting portraits, which are large-scale (slightly over five feet high and three feet wide), were then overlaid with thousands of lines of poetry: these words were carefully inscribed onto the faces so as to accentuate wrinkles and expressions and grief, yet remain barely visible except in a magnified view. The various clusters of images on the walls detract from the space one might have hoped for to engage intimately with each face, but the instinct, still, is to move forward and examine. By her own admission, Neshat acknowledges calligraphy is often a “cheap trick” that is used to sell otherwise pallid artwork from the Middle East. In this case, her touch is so light, so deferential to the faces and the experiences they record, that it would be easy to overlook the text completely. There is also a measure of respect, restraint, in Neshat’s choice not to include in the exhibition any of the stories that her subjects shared.

In the years since 2011, certain visual tropes have become common in art dealing with the Arab Spring: collage and graffiti, for example, often featuring or made by young people and drawing on such equally exhausted themes as “hope,” “change,” “defiance.” But the people Neshat chose to photograph were all elderly, their faces already deeply worn. Neshat recalled her father’s face to me before he died in Iran: “He cried all the time from all he had seen.” And it is perhaps this, her own long history as a witness to turmoil and suffering, her empathy with it, her distant understanding of uprising and change, that makes this work so much more penetrating than much of the recent work dealing with “revolution.”

Advertisement

Interspersed between these Cairene faces—a selection of sixteen from the forty she and Larry shot over the course of a week—are large portraits of feet, shown with white tags attached to a toe. These images, shot later in New York, mirror ones that Neshat had seen in Cairo last summer, images that had emerged from the morgue. The tags, identifying the dead as morgues do, are also inscribed, but this time with details of the lives the artist imagined the deceased to have lived—the only real fiction in “Our House Is On Fire.”

The cumulative effect marks something of a departure for Neshat. Although she has worked “on site” in the past, including in Morocco, this is the only work that is grounded more in fact, in reality, than in an enactment of a fiction. It is also equally representative of men as it is of women. “It’s the first time I do something so close to the truth,” Neshat told me. “It offers a sense of relief, but it’s also very heavy.”

Egypt offered Neshat an opportunity to create something real, almost documentary, perhaps for the first time since her forced exile. In our correspondence last summer, she had written: “Perhaps that’s why I became an artist—my imagination became my sanctuary, a place where I could be truly myself; a place where I could build a fictional bridge in between myself and my country…re-interpreting historical narratives which I’ve never witnessed but only imagined.” Her work on Cairo, is, perhaps, in its own way work on her home, Iran.

For those of us who were part of the revolution, who have experienced the cycles of hope and despair, who see these faces, hear these stories, in our everyday lives, “Our House Is On Fire” captures a reality that surrounds us, yet has been all but overlooked in the continuing story of the Arab uprisings: the reality of a country struggling with despair. That it took an Iranian to capture it suggests just how much more time Egyptians may need to gain perspective on the past three years, even as we are the ones who are telling the story.