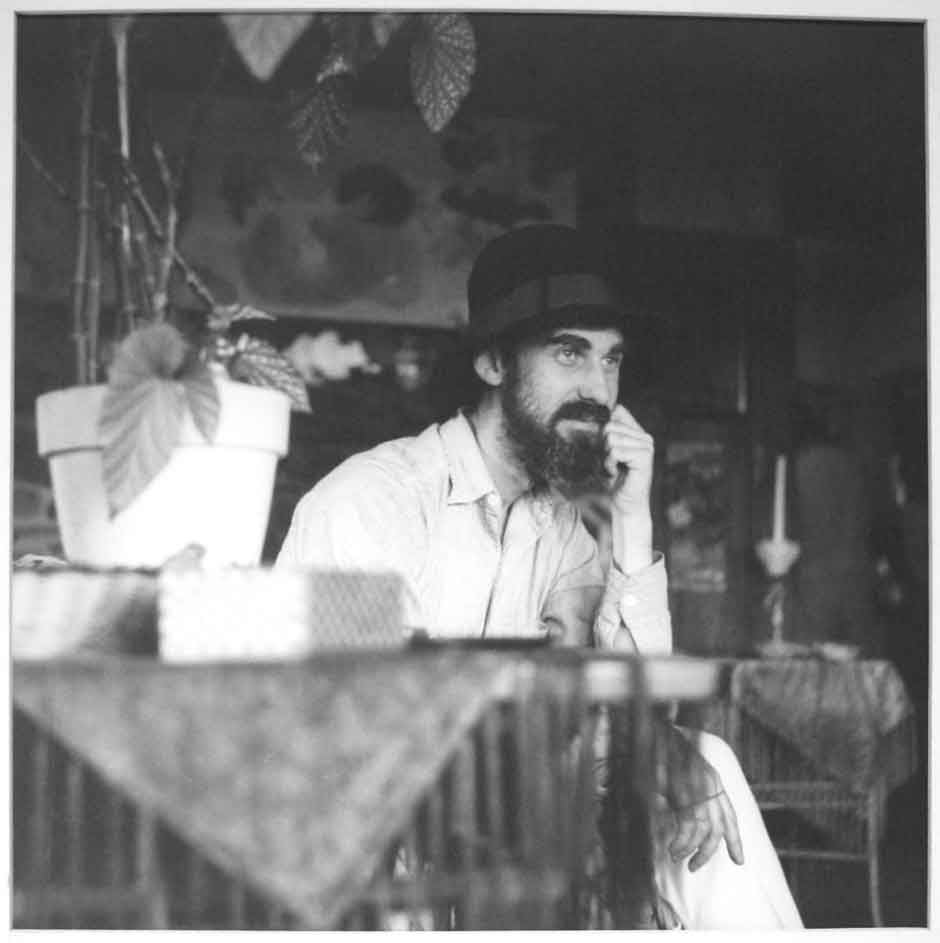

In the summer of 1950, a young man named Jess (he had dropped his surname after deciding to become a visual artist) heard Robert Duncan read his poetry, in Berkeley, California. The two shared many of the same passions: Frank Baum’s Oz books, James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, mythology and magic. They fell in love, and by the following winter had moved in together, thus beginning a lifelong relationship (Duncan died in 1988, Jess in 2004) that included frequent artistic collaborations, influenced a wide circle of painters, sculptors, filmmakers, and writers, and inspired the couple to create a series of households (most notably, a Victorian in San Francisco’s Mission District) whose decor reflected the broad range of their enthusiasms and their lively, colorful aesthetic.

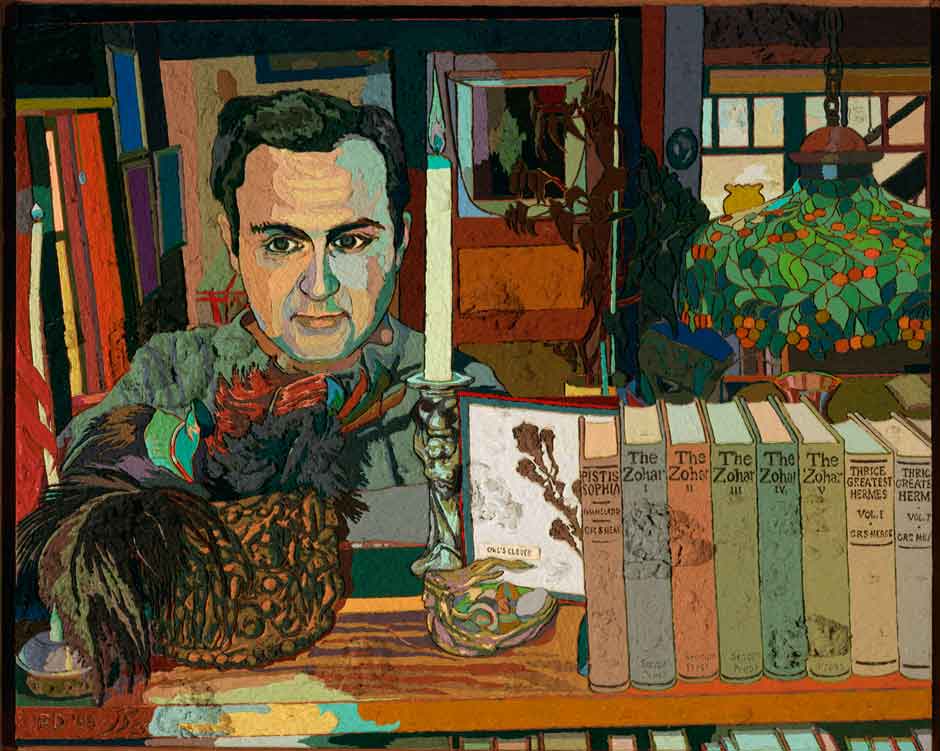

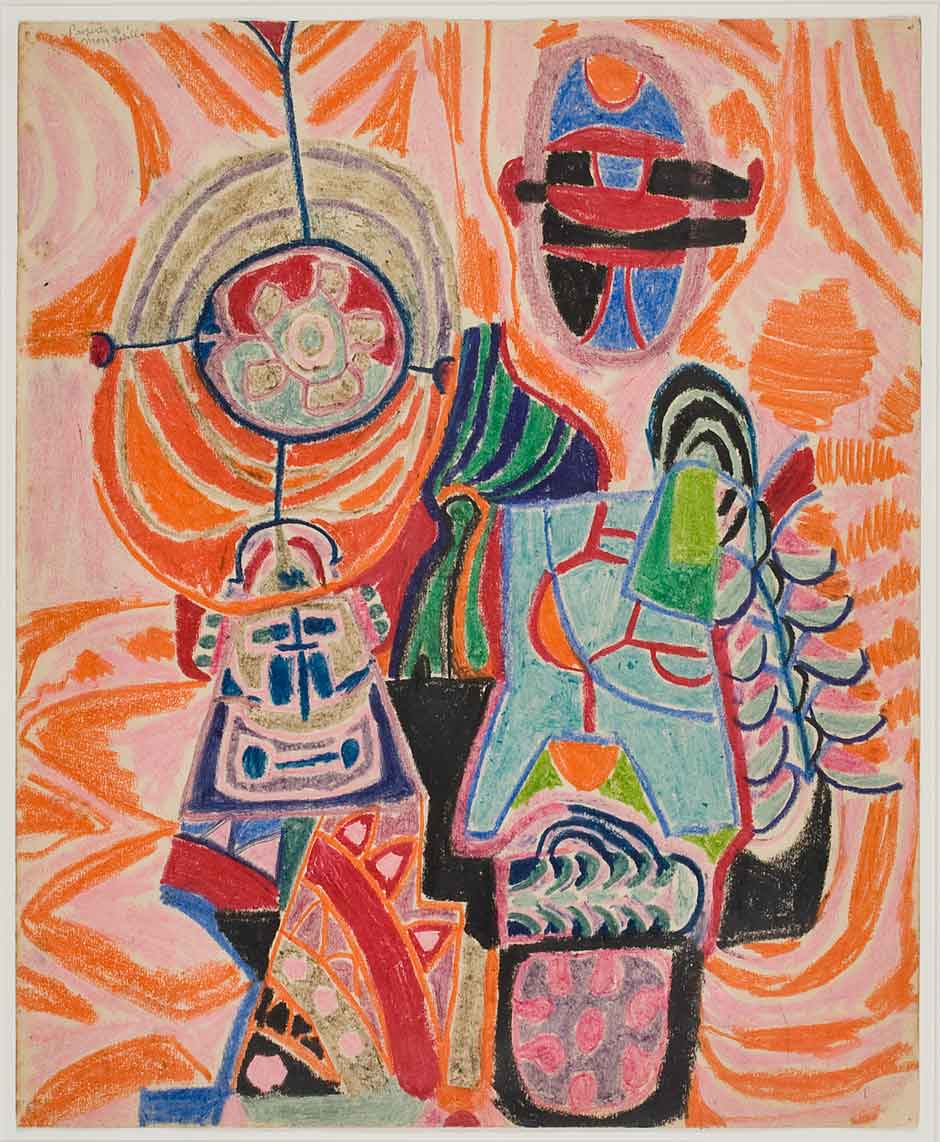

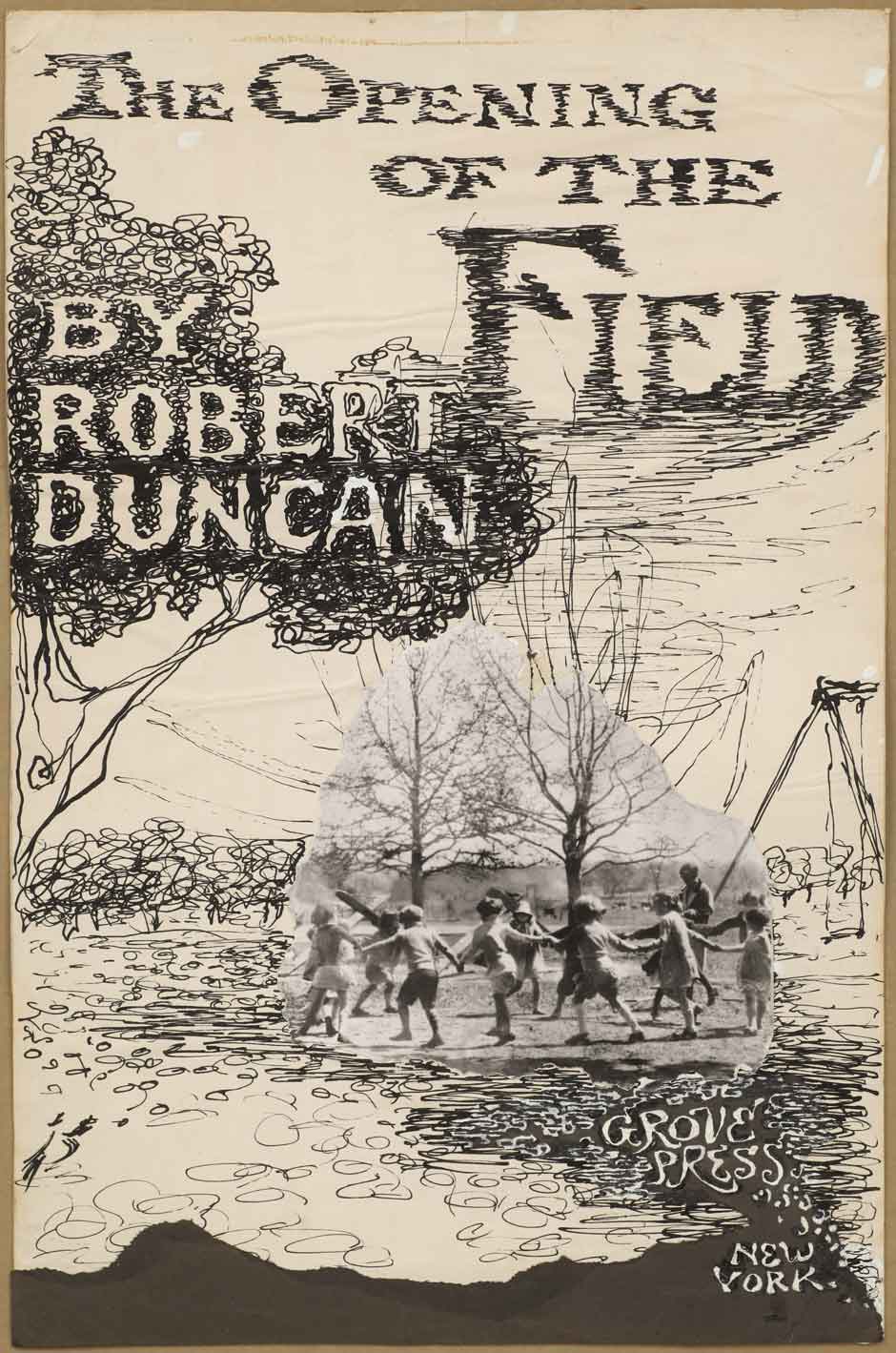

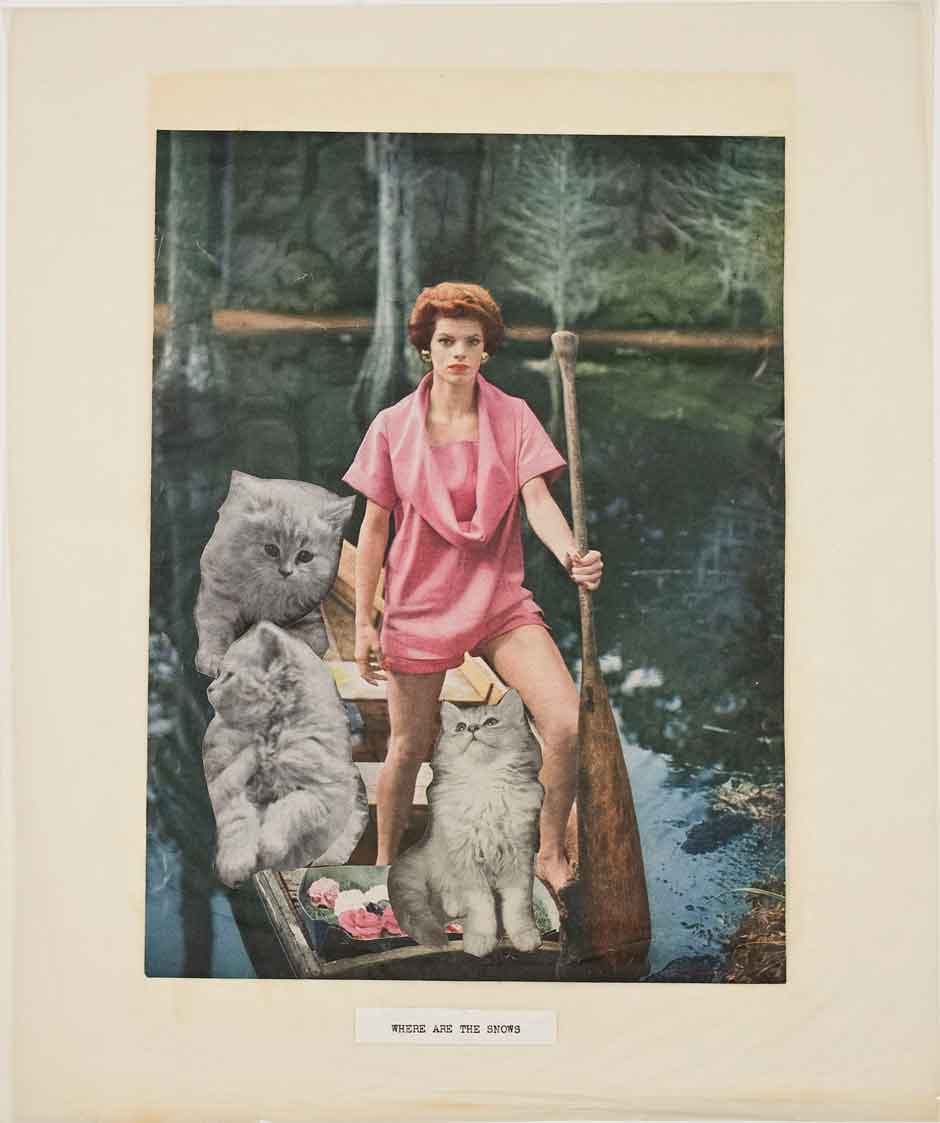

Their work, and that of the artists who made up their community, is the subject of a show, “An Opening of the Field: Jess, Robert Duncan, and Their Circle,” currently on view (until March 29) at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery and also of an excellent catalog, published by Pomegranate Communications. Curated by Michael Duncan and Christopher Wagstaff, the exhibition includes Jess’s paintings and “paste-ups,” a term he preferred to “collages.” One is struck by the bravery of the openly homoerotic imagery that Jess employed in work done during the 1950s, and by the tenderness and excitement evident in the art that the two men made, especially during the early stages of their love affair. He drew images from sources as diverse as Dick Tracy comics, medical textbooks, classical engravings, and beefcake magazines, fashioning them into various shapes, many of which were mythologically inspired. His first “paste-up,” A Mouse’s Tale (1951), shows a giant, crouching man whose body is composed entirely of nude and half-nude bodybuilders cut from magazines.

Before he met Duncan, Jess, born Burgess Collins, had worked as an atomic chemist, helping to produce plutonium for the Manhattan Project. Plagued by anxiety about the possible consequences of his work—and particularly by a dream that the world would be destroyed in 1975—in 1949 he left the world of science for the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. Not long after, he met Duncan. The influence of each on the other was visible almost immediately. Even as they were first getting to know each other, Duncan wrote “The Song of the Borderguard,” considered one of his finest poems, and later illustrated by Jess. Duncan said that the writing of this poem made him realize his love for Jess.

The exhibition shows a number of such books and broadsheets of Duncan’s poetry illustrated by Jess, an LP recording of Duncan’s poetry for which Jess designed the cover, Duncan’s own paintings and drawings, which owe a debt to Picasso and Matisse, and a section of wallpaper that Duncan created for one of their homes. There is also a film of Duncan reading his poetry, photographic portraits of Jess and Duncan by Patricia Jordan, and a pair of posters that Jess made for films (The Importance of Being Earnest and Jean Renoir’s The Golden Coach) that were shown in the late 1950s and early 1960s at Berkeley’s Cinema Guild and Studio, which was then being run by one of their friends, Pauline Kael.

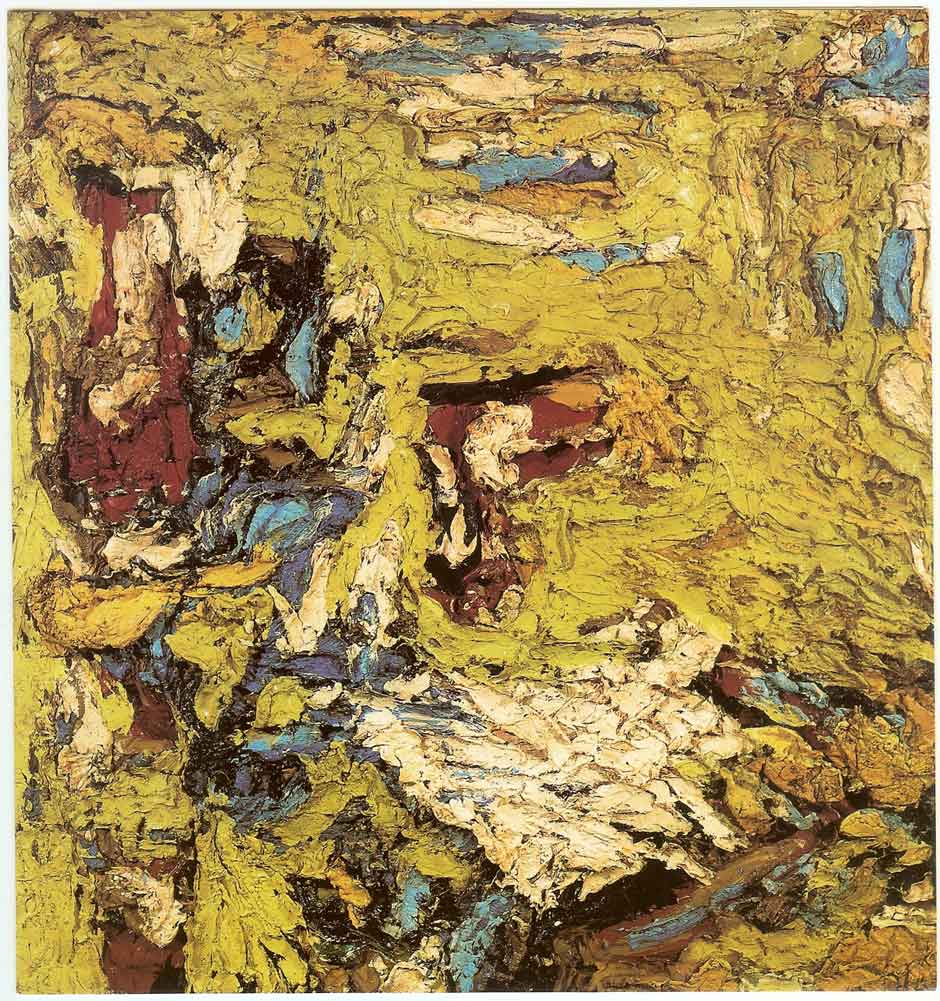

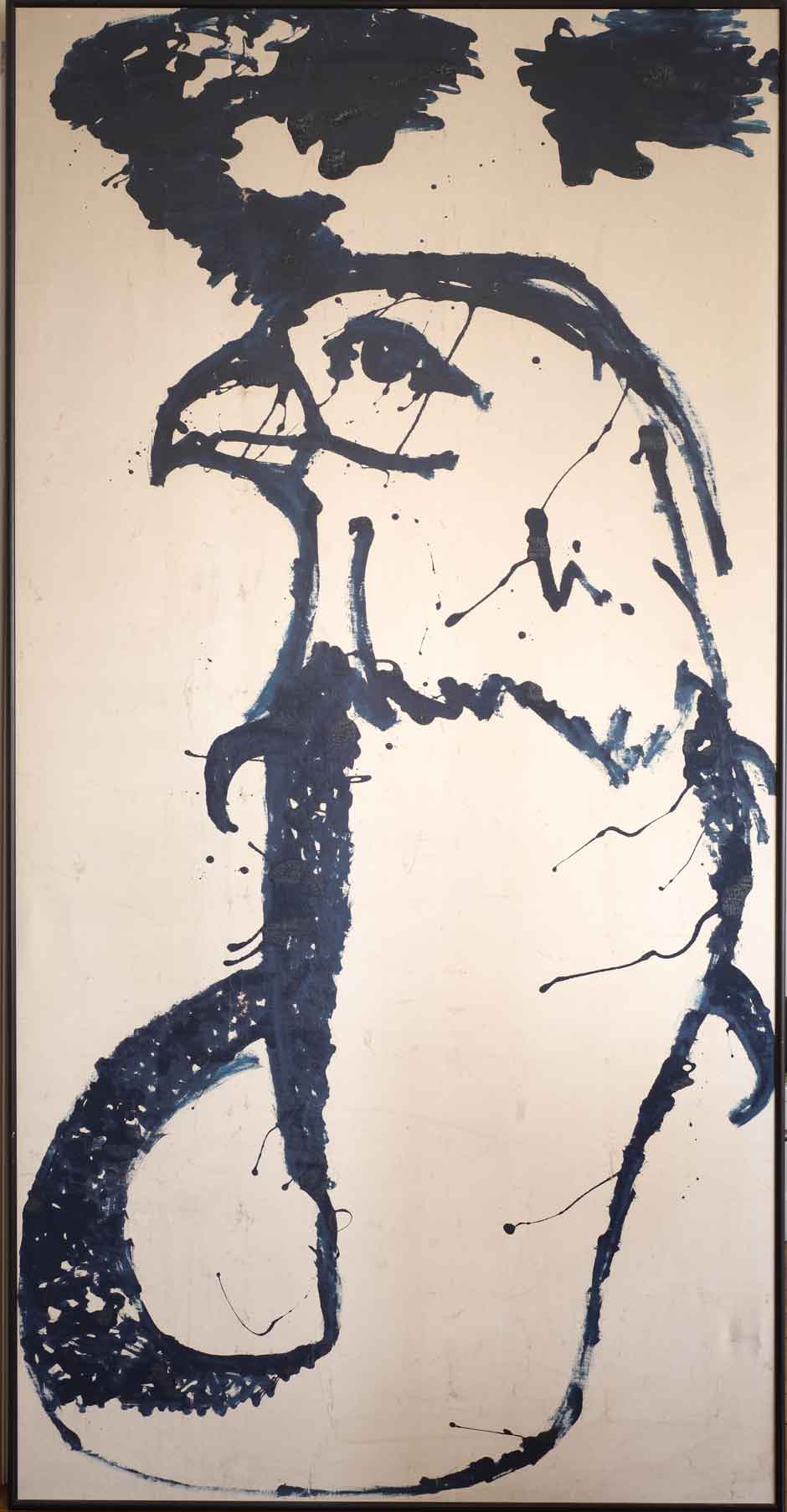

Kael was only one of the gifted writers and artists drawn into Jess and Duncan’s orbit. Among the more familiar are R.B. Kitaj, whose charcoal portrait of Duncan appears in the current show; the poets Denise Levertov, for whom Jess created a book cover, and Michael McLure, represented here by a painting, “Snake Eagle” (1956); and Robert Dean Stockwell, a painter who became much better known—under his middle and last names—as an actor. Included in the exhibition are eighty-five works by artists in Duncan and Jess’s circle, among them Virginia Admiral, Wallace Berman, Edward Corbett, Norris Embry, Nemi Frost, and Lyn Brockway; quite a few of them—Ernesto Edwards, Helen Adam, and Eloise Mixon, among others—made collages that are reminiscent of Jess’s paste-ups and which share a similar playfulness as well as a common interest in experimentation, mythology, and magic.

Visiting the show, it’s hard not to feel nostalgic…but for what? Perhaps for a time before young artists and recent MFA graduates were accustomed to droning on, with soporific self-seriousness, about their “art practice”; before the dictates of the art market had leached so much of the fun out of art; and before artists aspired to live in homes that closely resembled those of their wealthiest collectors. And though such considerations may be well outside the borders of the contemporary “art conversation,” the show makes it difficult not to reflect on the relationship between art and love: the ways in which passion, affection, and respect encouraged these two men—and the people around them—to set off in directions that might have been daunting, or unimaginable, to travel alone.

Advertisement

“An Opening of the Field: Jess, Robert Duncan, and Their Circle” is on view at the Grey Art Gallery through March 29. The catalog can be purchased from Pomegranate Communications.