In the spring of 1840, it was reported that the twenty-year-old Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, whom she had just married, had made some purchases from Claudet and Houghton of London. This was one of the first firms selling what were known as daguerreotypes, and the royal newlyweds bought views of Paris and Rome.

Certain cultural episodes and innovations corresponded closely with the six long decades of Victorian England, from a golden age of grand opera (which had few roots in England) to another of the novel (which did). One more was photography, which was almost exactly coeval with Victoria’s reign: those first daguerrotypes had appeared in 1839, two years after the girl-queen succeeded to the throne, and a discovery not identical but similar to the eponymous Louis-Jacques-Mande Daguerre’s had been made at the same time in England by William Henry Fox Talbot.

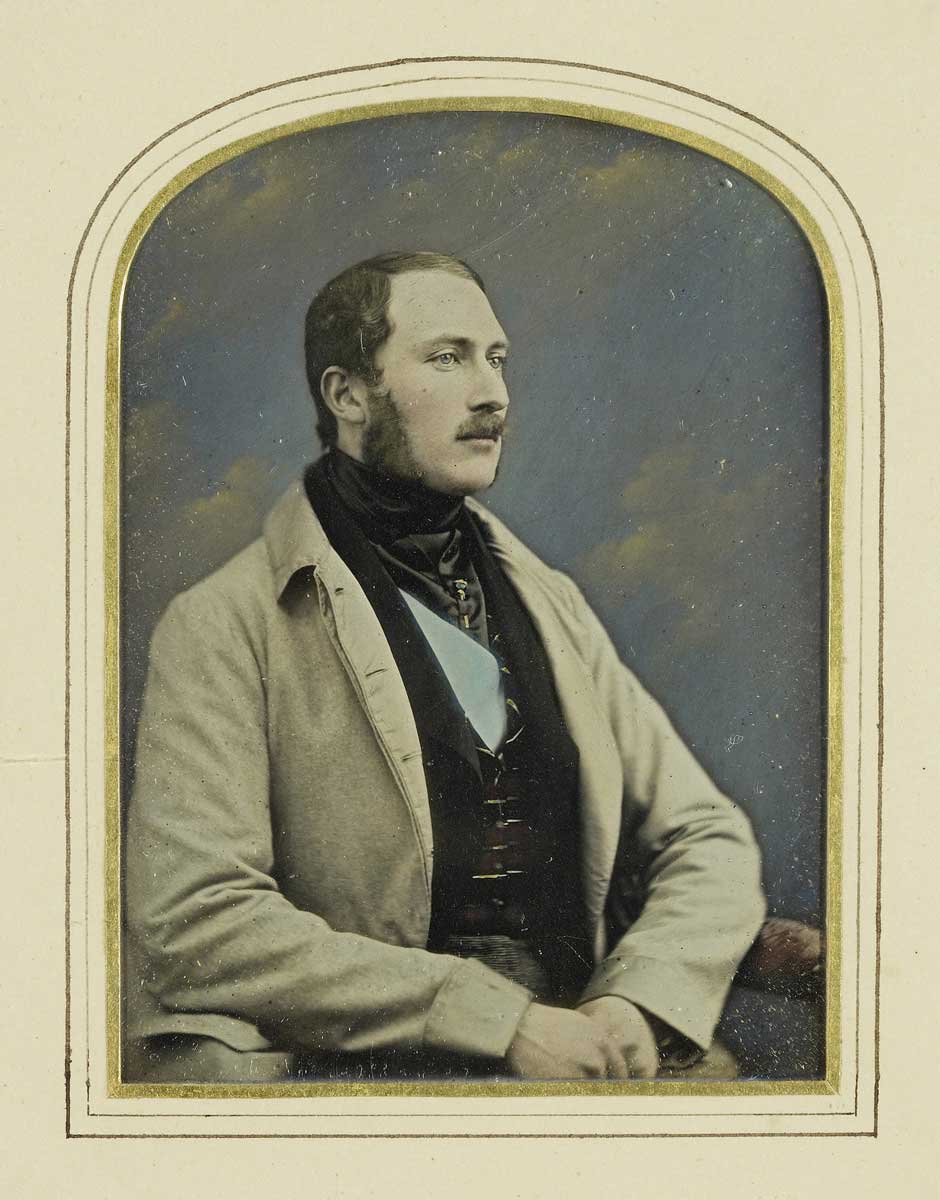

This absorption with the new medium can be seen at the new exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum and the handsome accompanying book by Anne M. Lyden, both called “A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography,” and both much enriched by photographs from the magnificent Royal Collection at Windsor. To begin with this was a private passion. Victoria and the husband she obsessively adored until his early death in 1861 (when he was photographed on his deathbed, as she was forty years later), and then even more obsessively mourned, collected photographs, but were not themselves photographed for public consumption.

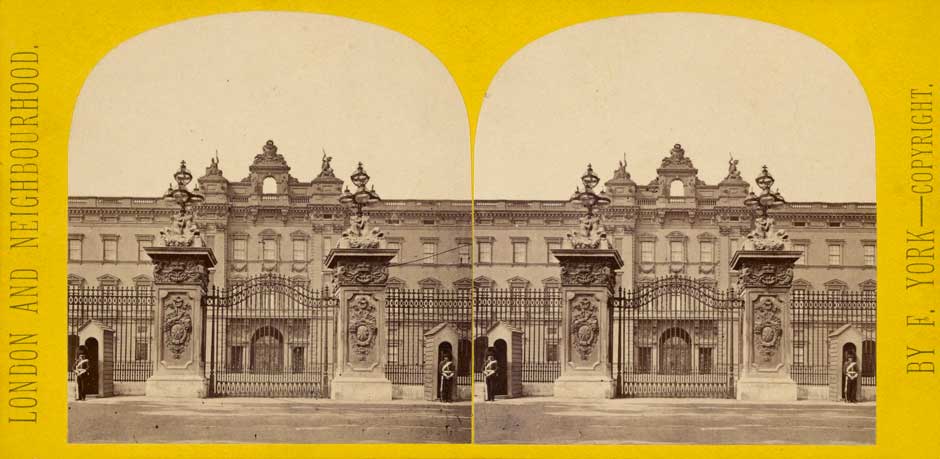

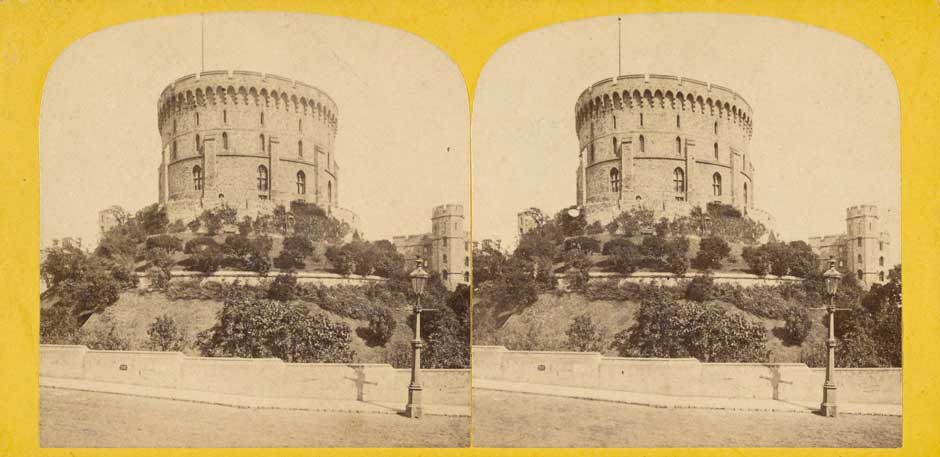

Portrait photography, as opposed to architectural photography such as Roger Fenton’s handsome photos of the royal residences at Windsor, Osborne, and Balmoral, was not in any case easy in the first years, as the subject had to sit or stand still for the several minutes that exposure took. But when they were at last published, photographs of the queen, prince consort, and their children played a most important part in another innovation—or invented tradition?—which we know as the “royal family.”

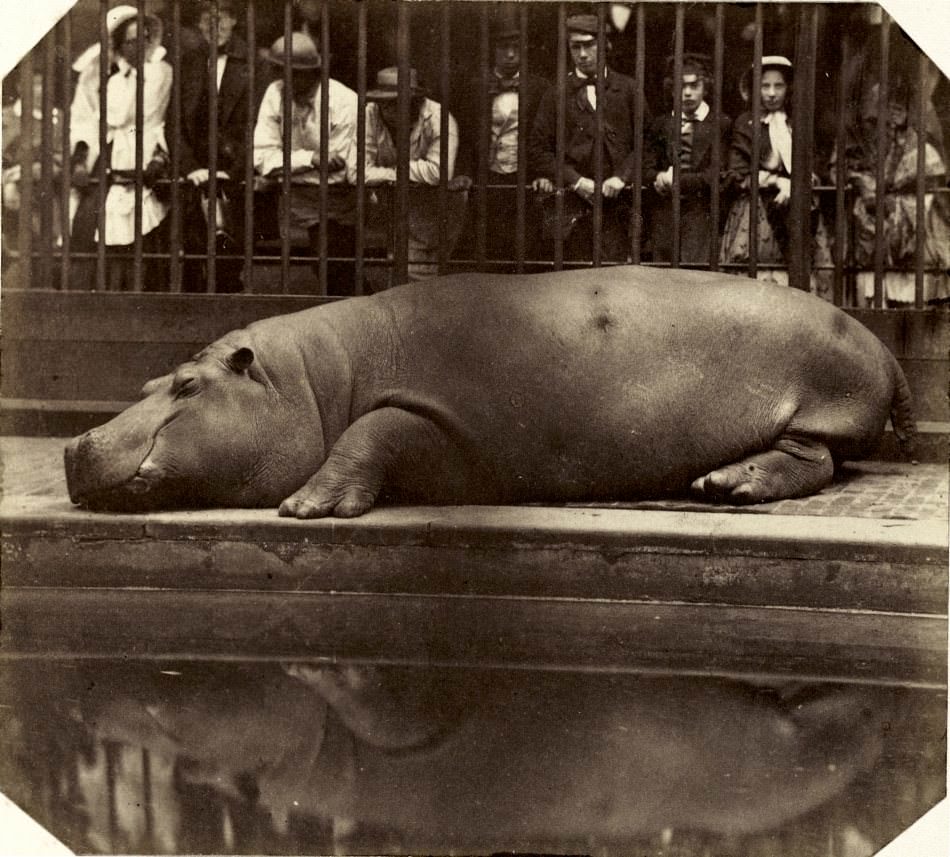

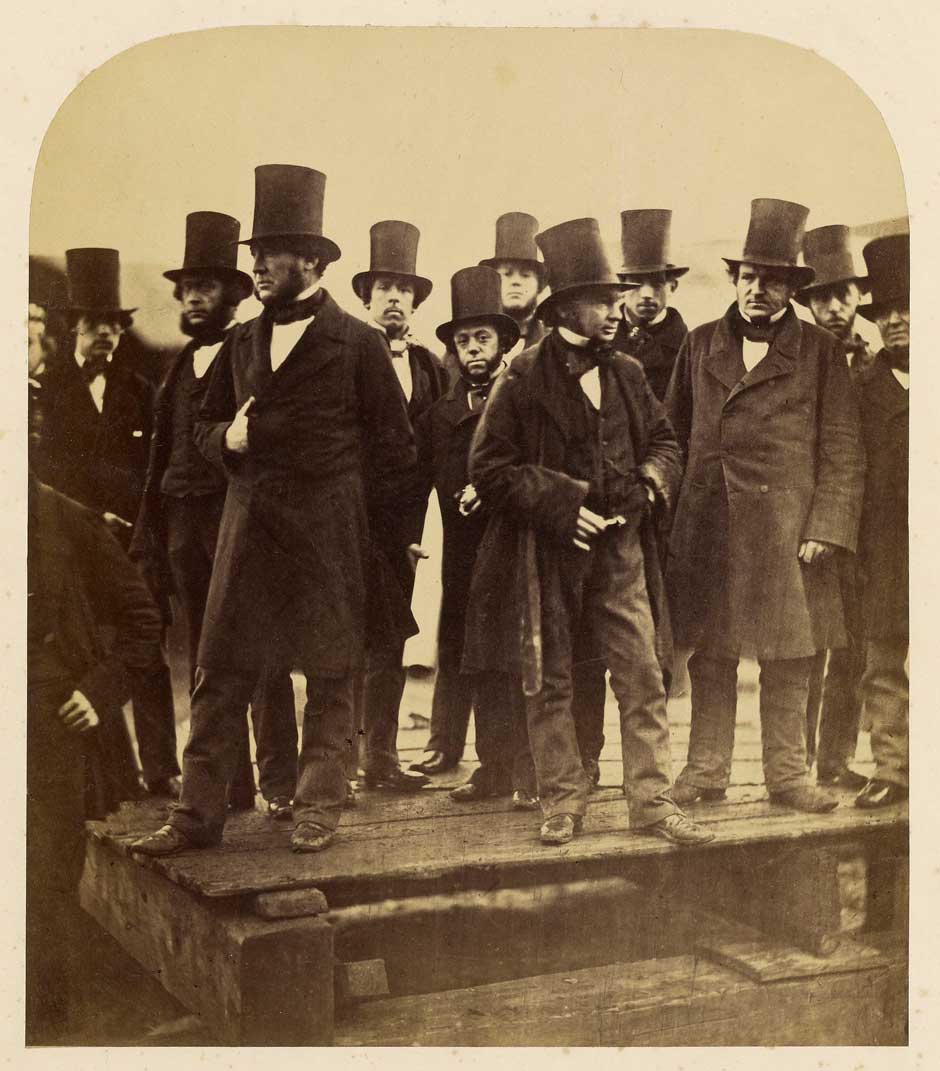

Photography, and the royal interest in it, emerged into public light with the Great Exhibition of 1851, partly Albert’s brainchild. Many of the astonishing six million people who visited the exhibition in Hyde Park saw photographs for the first time. Shortly afterward, the Photographic Society was formed with Victoria and Albert as patrons. Victoria admired and had patronised Roger Fenton, and when she visited the Society’s first exhibition, he was there and “explained everything,” the queen wrote. She was also delighted by “a set of photos of the animals in the Zoological Gardens,” including a charming hippo seen here. These were the work of the most socially illustrious of amateur photgraphers, the Count de Montizon, Carlist pretender to the Spanish throne.

As to the queen herself, an early miniature painted portrait by Sir William Ross managed to make Victoria almost pretty, and the 1846 group portrait of the Royal Family by Franz Xavier Winterhalter is charming, or gemütlich. But it was in later photographs that the queen’s unmistakable features, plump, bun-faced, unsmiling in widow’s black, and wearing a small crown in state portraits, such as that by W & D Downey, became a universal image, at home and throughout the empire; an image which the name “Victorian” brings to mind even now.

“A Royal Passion” is on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum until June 20, 2014.