Randall Jarrell was the kind of literary critic who carried a knife in his shoe. It would be possible to quote him for hundreds of brilliant and biting pages: of the poetry of Oscar Williams, he wrote that it gave the impression of “having been written on a typewriter by a typewriter.” Auden’s The Shield of Achilles was “Non-Euclidean needlepoint, a man sitting on a chaise lounge juggling four cups, four saucers, four sugar lumps, and the round-square: this is what great and good poets do when they don’t bother even to try to write great and good poems.” And, of poets as a species: “It is always difficult for poets to believe that one says their poems are bad not because one is a fiend, but because their poems are bad.” Where he loved a writer, his words in their favor are more convincing and seductive than any other critic of his generation; as when he wrote of William Carlos Williams that “the underlying green of the facts always cancels out the red in which we had found our partial, temporary, aesthetic victory.” Like Roger Ebert, the late much-adored film critic, his love of the medium came out both in his encomiums and his massacres. Robert Lowell wrote about his friend’s “harsh luminosity.” He was a man to want on your side.

For those who know him as a hardboiled reviewer, a kind of Philip Marlowe of literary criticism, it would seem an anomaly that he wrote five books for children. For those who know his poetry, though, it might not be surprising at all. His later work especially drew often on images of childhood—as in “The Lost Children,” which begins “Two little girls, one fair, one dark/One alive, one dead, are running hand in hand.” The adult poetry speaks of a desire for a lost innocence. This becomes a block in Jarrell’s work for children; great children’s literature has no truck with the idea that children are pure, as the target audience is very aware that they are not. Children, as children know best, can be nasty, brutish, and short. J. M. Barrie knew it; the closing sentence to Peter Pan makes it clear: “and thus it will go on, so long as children are gay and innocent and heartless.” Sendak, the illustrator of several of Jarrell’s books, knew it; Where the Wild Things Are is as chaotic as it is gleeful. And Jarrell’s stories are best when they are at their most dark and strange.

The least successful are The Gingerbread Rabbit, which is a humorless retelling of “The Gingerbread Man,” and The Bat-Poet. The Bat-Poet is the sweetish story of a bat who longs to stay up during the day and sing the song of the mockingbird; to his delight, he discovers that he himself can be a songster. The problem is that the poetry in The Bat-Poet is weak, in that distinctive mode of the bad poetry of the 1960s: “on the willow’s highest branch, monopolizing/Day and night, cheeping, squeaking, soaring/The mockingbird is imitating life.” It is wordy and sentimental, which is perhaps not absolutely surprising in view of Randall’s critical style; acerbity and sentimentality can be two sides of the same coin.

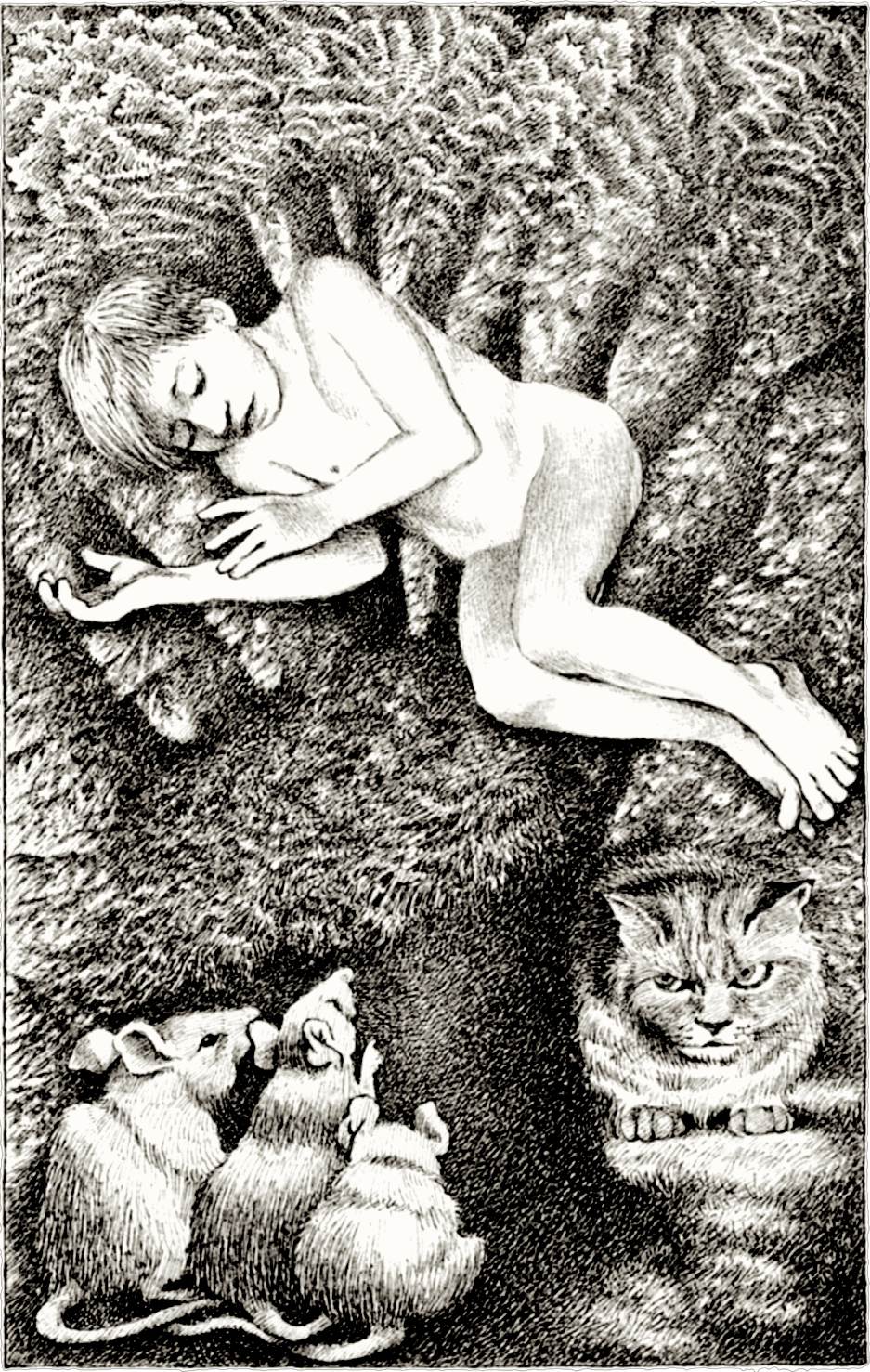

In Fly by Night the story is stranger and stronger—a boy floats at night, alone, over the sleeping world. The Sendak illustrations are extraordinary and beautiful; they show a child floating, feet first and naked, over cats and rats the size of his torso. But there is, again, the awkward poetry, which reaches for a bedtime sweetness it does not absolutely achieve: “All night the mother would appear/And disappear, with good things; and the two/Would eat and eat and eat, and then they’d play.” The final line of the book, though, is a great one, and calls to mind the quicksilver nature of dreams; “He can remember, he can almost remember, but the sunlight streams in through the windows, he holds his hand out for the orange juice, and his mother looks at him like his mother.”

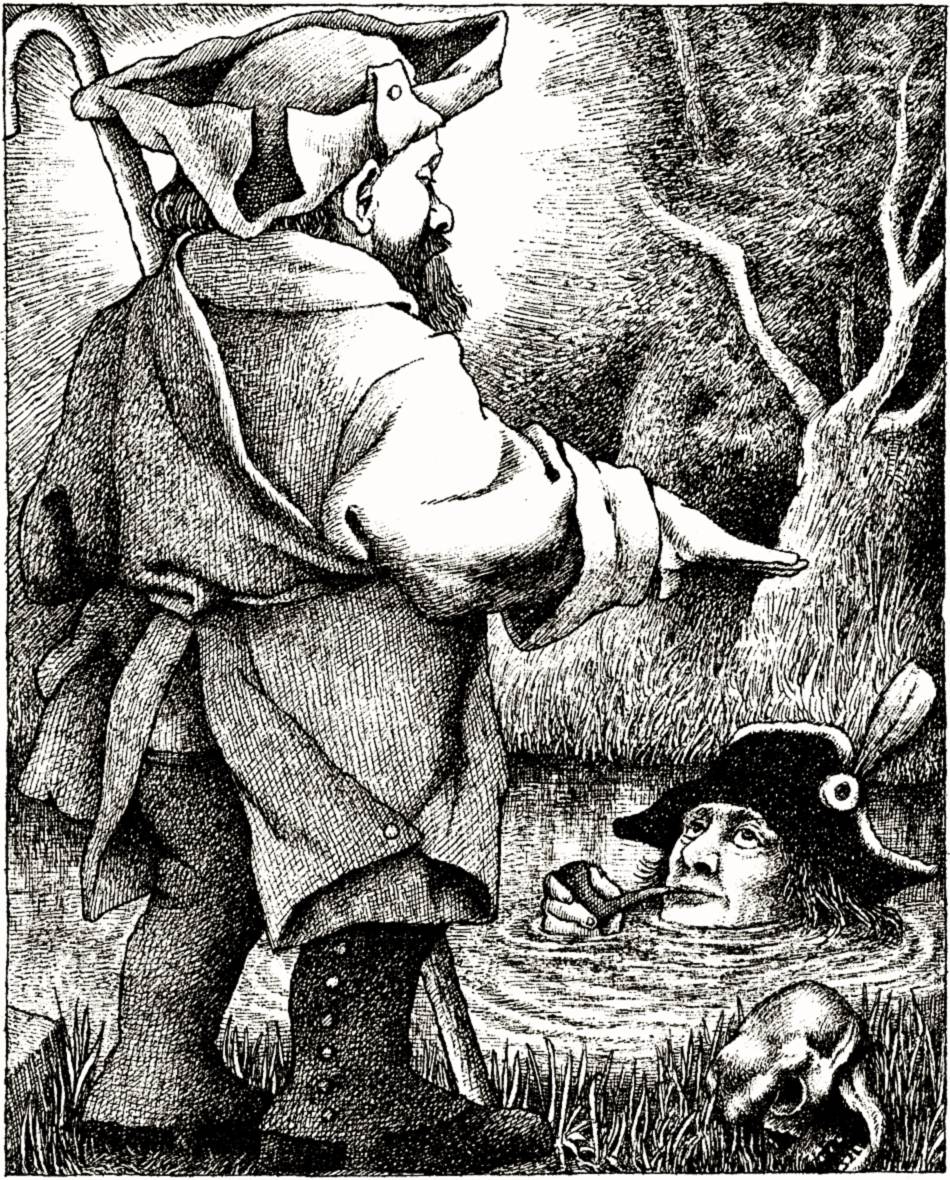

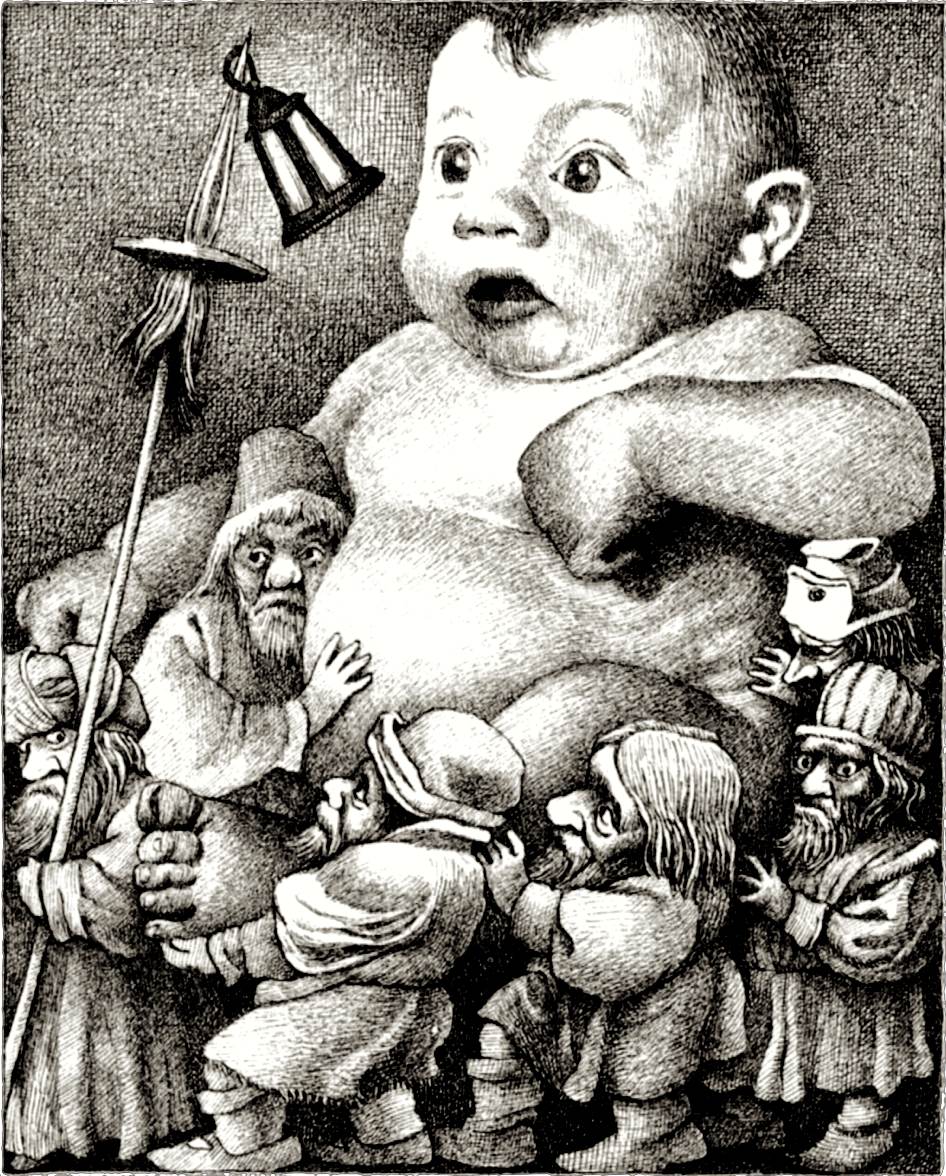

The translations of Tales from Grimm, published as The Juniper Tree, are a different story; the Grimm tales will always be unwieldy and harsh, and Jarrell brings some of the dryness of his critical writing to the task. In “The Goblins,” there is a Jarrellian bite in the swiftness of the narration, which is less than two pages long.* “Once there was a mother and the goblins had stolen her child out of the cradle. In its place they laid a changeling with thick head and staring eyes who did nothing but eat and drink.” Sendak’s illustration of the goblins hauling the rightful baby back is predictably wonderful, all down-turned mouths and resentful eyes and hands.

Advertisement

The best, though, is The Animal Family, which won a Newbery Honor in 1965. Again illustrated by Sendak, it is gentle and unsettling by turns. In it, a hunter and wife—a mermaid—adopt a makeshift family: first a bear, who grows with the prodigious speed of a son (“The mermaid said, ‘Why, if you put his chair in his bowl, he’d eat it’”), then a lynx (“‘Another boy,’ said the hunter equably”), and finally a human child. The family is bilingual in mermaid and human, but their dynamic is familiar; they care for and protect each other, they tame each other, they tell generous and necessary lies to each other. Jarrell captures in his prose the wistfulness he aims for in his poetry. As he once wrote, “one of the most obvious facts about grownups, to a child, is that they have forgotten what it is like to be a child.” The Animal Family is proof that he had not forgotten.

*“The Goblins” was translated by Lore Segal. Jarrell translated four other tales in the volume.