The photographs collected in Lee Friedlander’s Playing for the Benefit of the Band: New Orleans Music Culture, many of which are currently on display at the Yale University Art Gallery, were taken between the years 1958 and 1982, though I suspect I’m not the only resident of New Orleans who will do a double take at the datelines beneath the pictures. In the images of Mardi Gras the parade routes appear the same as they are today, the Creole cottages are the same, the floats are the same. The members of Zulu wore the same grass skirts, blackface makeup, and afro wigs in 1982 as they do today. The Mardi Gras Indian costumes haven’t changed either. Some of the brass bands Friedlander photographed played at the most recent JazzFest, just a couple of weeks ago (albeit with different members). If you could hear the music, it would sound the same too.

But Friedlander’s most indelible images are his portraits of musicians. Friedlander arrived in New Orleans at a high point in the jazz revivalist movement, when fans of jazz as it was originally played in New Orleans in the first two decades of the twentieth century (before the perceived corruptions of swing and bebop) descended on the city with tape recorders and notepads and cameras, hoping to catch some of the old magic and document it for posterity. Many of the musicians who pioneered the form as teenagers were still alive, and still living in New Orleans, when Friedlander first visited in 1957. While others recorded oral histories and took down reminiscences of Buddy Bolden, Friedlander photographed musicians like De De and Billie Pierce, Peter Bocage, and Ernest “Punch” Miller—musicians who, having languished in poverty and obscurity for decades, were enjoying in their dotage a belated, if rousing second act.

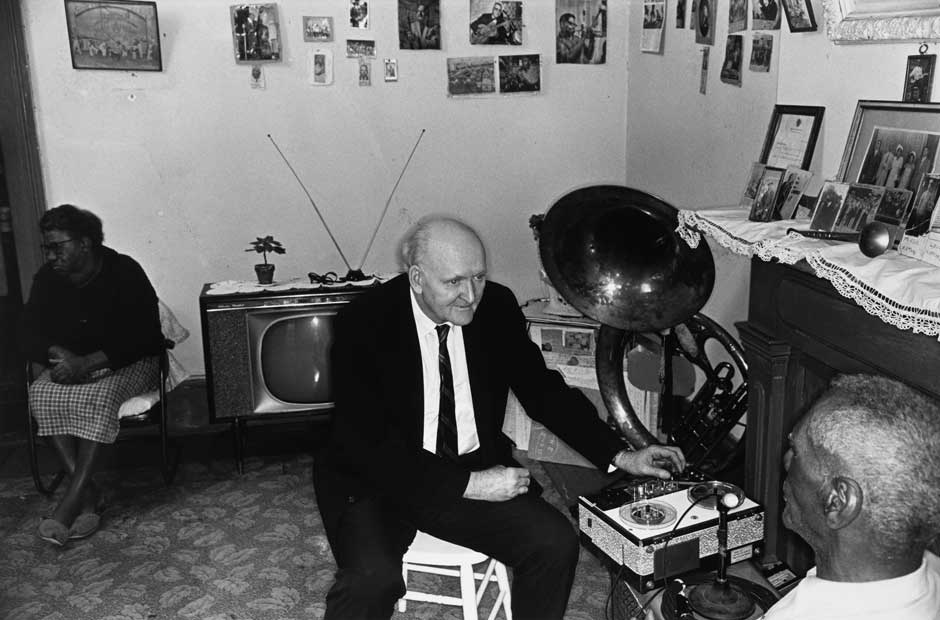

The attitude of the professional revivalists tended to be equal parts celebratory and anthropological. Several of the most prominent are pictured alongside their subjects in a series of photographs on the book’s final page. Richard “Dick” Allen, then the curator of Tulane University’s Archive of New Orleans Jazz, poses with Joseph “Red” Clark, a baritone horn player who once played with Bunk Johnson; Allan Jaffe, an owner and manager of Preservation Hall, is pictured singing with Sister Gertrude Morgan, the evangelical artist, street-preacher, and gospel singer; and the composer and musicologist William Russell, the original curator of the Tulane jazz archive, is seen interviewing Louis Keppard, a guitarist who played with King Oliver, Papa Celestin, and Honore Dutrey. These revivalists guided Friedlander around New Orleans, eschewing the French Quarter for local dance halls, rehearsals, neighborhood lounges, and country funerals. They did the same favor for many others, including Whitney Balliett, who wrote about the experience for The New Yorker in an essay (“Mecca, LA”) that later served as the introduction to The Jazz People of New Orleans, a previous incarnation of Friedlander’s New Orleans photographs.

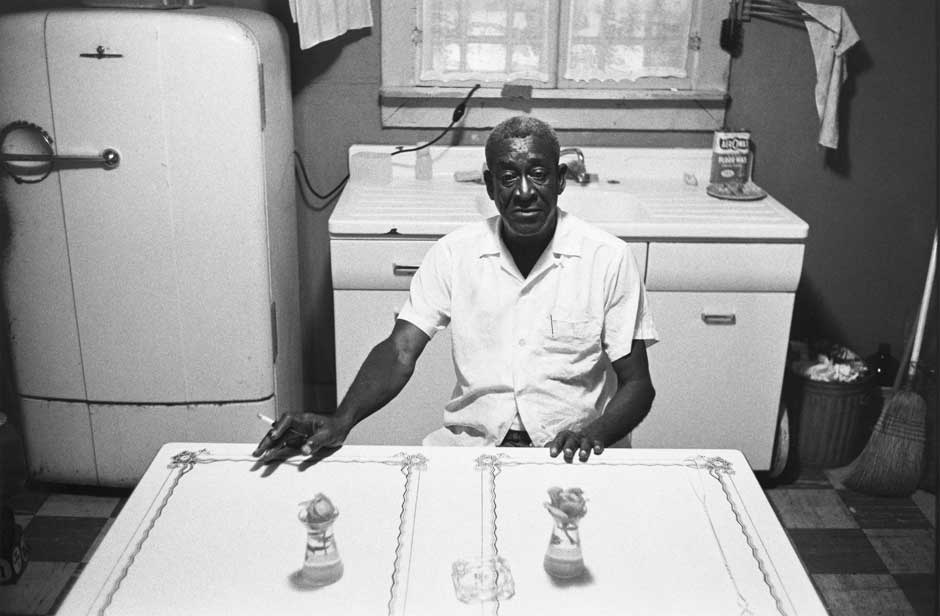

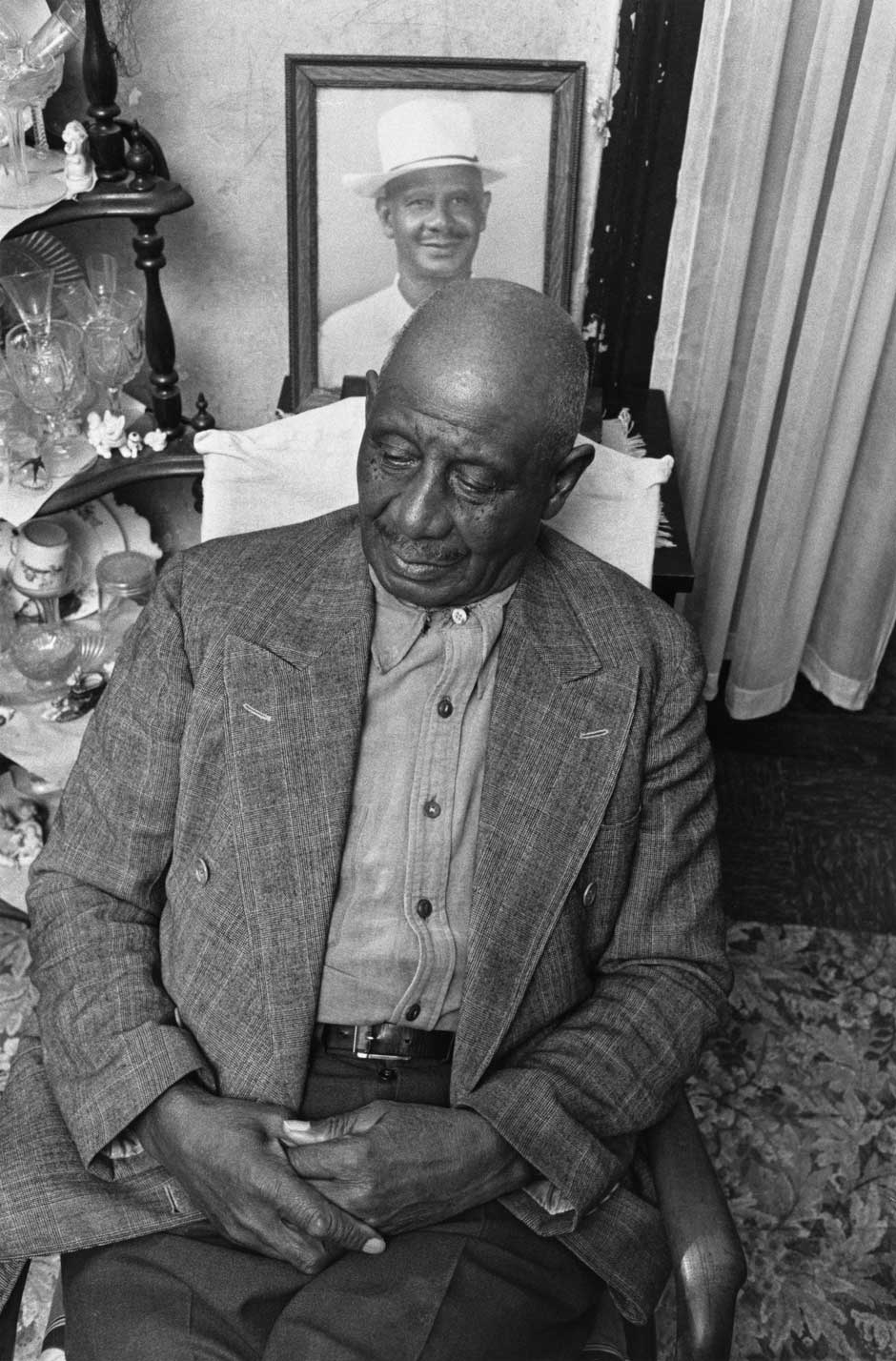

Friedlander’s portraits do not feel celebratory, however. He found authenticity all right, but authenticity does not only take the form of an Irish Channel dive where, as Balliett wrote, the music was “primitive, unhurried, and perfectly executed.” Friedlander found authenticity in the toll taken on his subjects by decades of privation and indifference. In his portraits the musicians—most of whom didn’t have the chops to follow Joe Oliver and Louis Armstrong north to Chicago forty years earlier—stare wistfully into the distance, or at the wall, as if indulging in some bittersweet private nostalgia. Many sit beside old family photographs, including pictures of themselves as young men. Some are photographed with their instrument, which they hold impotently, or rest in their laps. Their apartments are spare and poorly lit. There is dignity in these portraits, to be certain, and pride, but there is also despair.

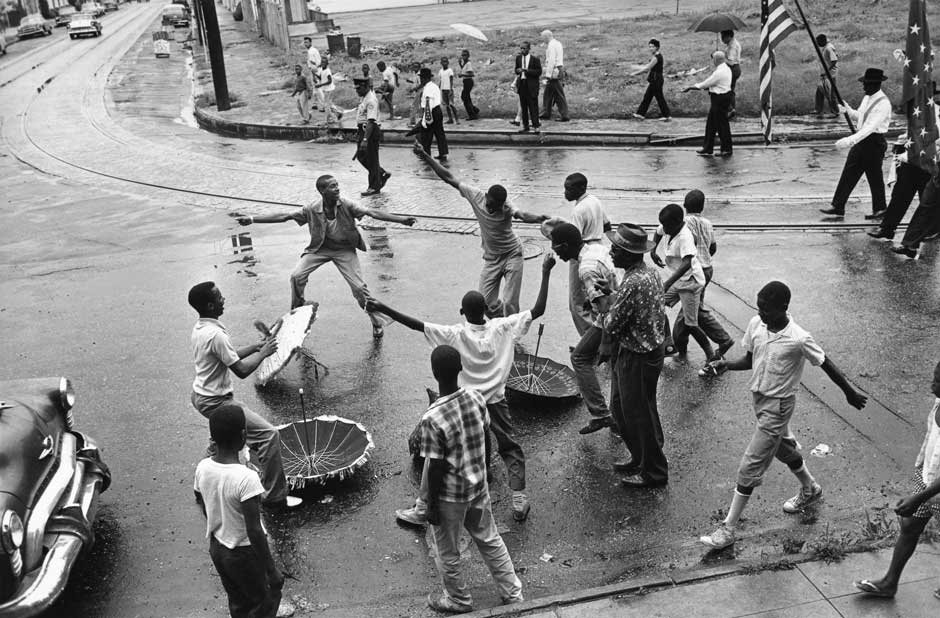

This sense of melancholy also shadows Friedlander’s photographs of performances. When George Lewis’s band plays a Bourbon Street tourist trap called the Paddock Lounge, the ceiling is so low that he almost has to duck, and nobody else in the frame—a patron, two bartenders—seems aware that they are in the presence of jazz royalty, an impression that is amplified by the insulting presence of the lawn jockey posing directly in front of Lewis. There are no audience members, for that matter, visible in most of the performance pictures, giving the impression that the musicians are playing for themselves. An additional grim irony attends the photographs of a brass band playing a funeral parade, when one realizes that every member of the Young Tuxedo Brass Band is an old man.

In Balliett’s 1966 essay he is told by Dick Allen that “New Orleanians in general don’t care about jazz.” Balliett, testing that claim, stops by the New Orleans Tourist Commission and asks where he might hear some good jazz. The attendant looks startled. “I’m sorry,” she says, “but we can’t help you. We don’t have anything on jazz.”

Advertisement

It’s safe to say that no member of the New Orleans tourism industry—the city’s leading industry—would say they “don’t have anything on jazz” if asked that question today. And they must be asked hourly, if not by the minute. There are now dozens of clubs both in the French Quarter and on Frenchmen Street that, like Preservation Hall, offer the “Traditional New Orleans Jazz” experience. The revivalists have triumphed. Tourists are inundated with the music from the second they land in Louis Armstrong Airport. There is something jubilant about the preservation of this embryonic form of jazz, frozen in time for a century, but there’s something haunting about it too, and it’s this duality that gives Lee Friedlander’s photographs their unsettling beauty.

Jazz Lives: The Photographs of Lee Friedlander and Milt Hinton is on view at the Yale University Art Gallery through September 7, 2014. A companion volume, Playing for the Benefit of the Band: New Orleans Music Culture is available from Yale University Press.