In 1909, Henry James wrote of seeing Paolo Veronese’s The Family of Darius before Alexander in London:

You may walk out of the noon-day dusk of Trafalgar Square in November, and in one of the chambers of the National Gallery see the family of Darius rustling and pleading and weeping at the feet of Alexander. Alexander is a beautiful young Venetian in crimson pantaloons, and the picture sends a glow into the cold London twilight. You may sit before it for an hour and dream you are floating to the water-gate of the Ducal Palace.

Long regarded as among the greatest Venetian paintings, it has attracted the intense admiration of many writers, including Goethe, Hazlitt, and Ruskin, as well as James. Its acquisition by the National Gallery in 1857 was considered a triumph; Queen Victoria even made a special visit to the museum just to view the picture.

It is now one of the high points in the magnificent show about Veronese on view at the National Gallery, the first comprehensive exhibition of the painter in over twenty-five years. For much of the twentieth century Veronese was regarded more as a skilled purveyor of decorative finishes than as a profound master, and his reputation was in decline, but of late there are signs of renewed interest, which this show and its catalog will certainly do much to advance. Perhaps more than any other picture in the show, The Family of Darius before Alexander reveals his great strengths as a painter; it also makes clear why he can seem so foreign to common modern ideals of art and of the artist.

Made around 1565–1567, the painting represents the widow and daughters of the Persian emperor Darius, who beg on their knees for mercy from Alexander the Great; they mistake Alexander’s friend Hephaestion for the Greek conqueror, and yet such is Alexander’s magnanimity that he forgives them nonetheless. All the other figures surrounding the main group—the dwarf and monkey, the lords and ladies and horses in the background and in the flanks—are there merely to amplify the sense of momentous and stately occasion.

Remarkably, despite its gigantic scale—it is over fifteen feet wide and nearly eight feet tall—the picture was commissioned by a private person, Francesco Pisani, for the decoration of his palace. It was in mid-sixteenth-century Venice and the Veneto that for the first time since antiquity private patrons regularly began to order artworks of a scale and grandeur previously reserved for heads of church and state. The Venetian elites of this era were immensely rich and deeply learned and they spent extravagant sums on the competitive display of their taste and culture, both in art and architecture. Typical of the ethos was Alessandro Piccolomini’s The Principles of the Happy Life, a book of moral instruction printed in Venice in 1545, which states:

A great man must never avoid the duty to spend on magnificent works…using all his genius…to always outdo the others…[by making] splendid villas, sumptuous gardens, and palaces in the city…in which every part is adorned and ornamented.

In building, the star of the age was Palladio—indeed, The Family of Darius before Alexander originally graced a palace designed by the architect. In painting, more than any other artist, Veronese knew how to glorify his patrons’ wealth, status, and erudition.

The confident hedonism of the artist and his patrons may be one reason that in the modern era, Veronese has often been regarded as a gifted but superficial painter, more interested in depicting grand spaces, tumultuous crowds, and sumptuous surfaces than in capturing the heart of the historical scenes he illustrates. Thus, Roger Fry sniffed that Veronese “doesn’t care a damn about anything but his opportunities,” and John Pope-Hennessy chided that “analysis was alien to the cast of Veronese’s mind.”

Yet The Family of Darius before Alexander reveals the seriousness of purpose with which Veronese worked. As few other painters of the Renaissance, he sought to make images that drew on the resources of all the arts, not just painting. Veronese had studied sculpture first, and the experience remained fundamental to his approach to image-making. His idea for any picture began with the main figure or figures, which he planned by emphasizing strong motion and forceful disposition in space. Like so many sculptors in the Renaissance, he saw the movements and gestures of the figures, not the expressions on their faces, as the primary means for conveying the emotional content of a scene.

It is typical that the only extant drawing for the picture shows five variations of Alexander’s stance and gesture, each with a slightly different air of natural grandeur, while rendering the head in the most minimal fashion. This emphasis on the body as the center of expression continues in the painting itself. In The Family of Darius before Alexander, as Hazlitt noted, the faces show little evident emotion. Yet Alexander’s graceful pose, outstretched hands, and inclined head all suggest his nobility and clemency. One early description of the picture called the scene “majestic,” another said it is “worthy of a prince.”

Advertisement

Veronese’s love of architecture was crucial to his art and career, and he worked closely with architects throughout his life. His first recorded employer was the great architect Michele Sanmicheli; he collaborated with Andrea Palladio on the Villa Barbaro at Maser and other projects; he worked for Daniele Barbaro in the very years that Barbaro wrote his important commentary on Vitruvius, even providing frescoes for a palace designed by Barbaro; and he found a mentor in the sculptor and architect Jacopo Sansovino. (Barbaro was a distant relative of Francesco Pisani.) The gracious arcade in the background of the picture recalls Sansovino’s Loggetta at the base of the Campanile in the Piazza San Marco, and other attempts in mid-sixteenth- century Venice to recapture the elegance and splendor of the classical past.

Veronese also had an abiding interest in theater. Barbaro and another of his patrons were members of the learned academy that built the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza, designed by Palladio; and Veronese may have designed the costumes for the initial production there, Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, which was the first public performance of a Greek tragedy since the end of antiquity. In The Family of Darius before Alexander the figures arranged in dramatic groups and posed before an architectural backdrop give the appearance of actors on a stage. The ornate and exotic costumes add to the air of spectacle and ceremony. Indeed, as Nicholas Penny has observed, it was probably the theatricality of the picture that especially attracted Goethe to it.

Veronese’s style is overtly rhetorical. In the Renaissance, painting was often said to be a form of mute poetry, but Veronese’s first biographer, Carlo Ridolfi, writing in 1646, instead compared his art to oratory. This comment may appear to emphasize the artificial, ceremonial, and unnatural qualities of Veronese’s art. But it was meant as praise: in the Renaissance, rhetoric was seen as the foundation of the humanities. It is striking to note that in 1557, the year after he published the first Italian edition of his commentary on Vitruvius, Daniele Barbaro also published a treatise about literature and rhetoric called On Eloquence. There he praises grandezza as the highest and most sublime style, appropriate for the most elevated topics. The elements he names as the main components of grandezza—majesty, vehemence, splendor, vivacity—read almost like a list of the qualities of Veronese’s art.

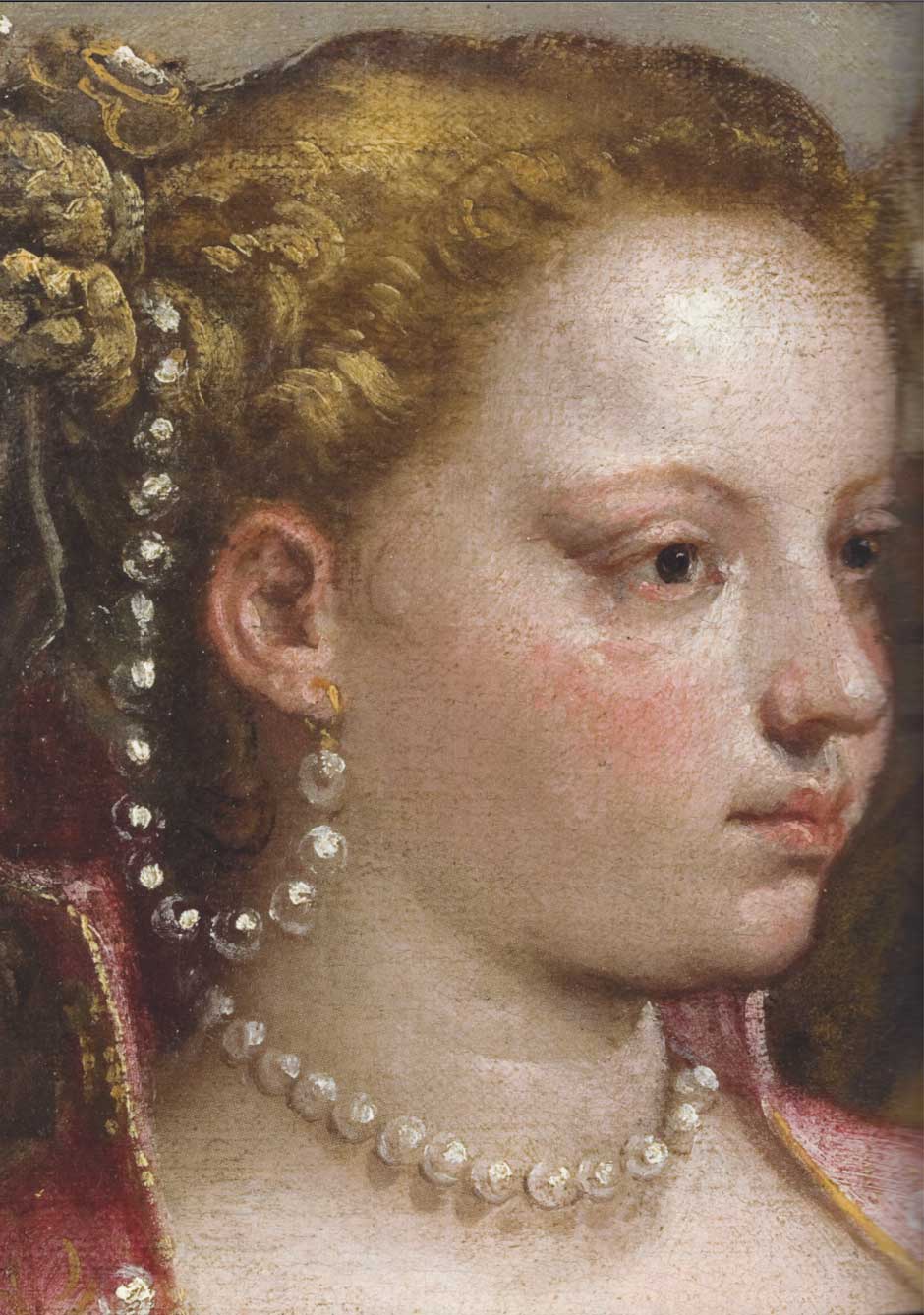

Above all, The Family of Darius before Alexander displays Veronese’s absolute command of paint and brush. Looking at this picture, the viewer finds it easy to understand why one of the earliest uses of the word “impression” in reference to a painting was in Ridolfi’s seventeenth-century biography of Veronese. The artist worked with breathtaking dispatch and unerring certainty, and was able to create almost any effect of light glinting and dancing off a variety of surfaces, from flesh and fabric to metal and jewelry.

No one has described Veronese’s virtuosity better than Ruskin, who wrote of a pearl worn by one of Darius’ daughters:

This he does with perfect care and calm; but in two decisive seconds. There is no dash, nor display, nor hurry, nor error. The exactly right thing is done in the exactly right place, and not one atom of color, nor moment of time spent vainly. Look close at the two touches—you wonder what they mean. Retire six feet from the painting—the pearl is there!

Veronese’s prodigious facility, love of magnificence, and untroubled service to the dreams of wealthy clients were all counted against him for much of the twentieth century. Few great artists have seemed less radical or rebellious. But this reaction overlooks his own ambitions as a painter. The show at the National Gallery makes it possible again to see why so many writers were drawn to this artist, and why so many painters, from Annibale Carracci and Giambattista Tiepolo to Delacroix and Cézanne, thought of Veronese as one of the supreme masters of art.

Advertisement

Veronese: Magnificence in Renaissance Venice is showing at the National Gallery in London through June 15.