Why do we love Stendhal?

We do not love him for his heroism, as he never was an indomitable conspirator for freedom or a martyr of any “right cause.” On the contrary, he shined in the Paris drawing rooms whose boredom he described with great venom; he held public offices although he felt diminished by the lack of appreciation for his own intelligence and former services; at the time of the domination of the “priestly party” he would say sacrilegious things like “God can be excused because he does not exist”—but that never brought any harm upon him. So he was neither a martyr nor a hero. He was a smart and insightful skeptic; he was wise with his wonderful irony and helpless anger. He was able to ridicule mercilessly because he could read the mysteries of the human soul.

We love Stendhal, this expert in pandering, for his lack of hypocrisy, for honesty toward himself, for dignity when confronted with villainy, and for the sense of intrinsic value devoid of narcissism and devastating megalomania. His political helplessness transformed into a general fury when he painted the picture of the Restoration and the gallery of characters of that peculiar era, when the characters collapsed and human souls degraded but France kept growing more powerful and people grew richer every month.

Obviously, not everyone grew richer. There were those who still lived in poverty. Stendhal was sincere in his solidarity with the people and, just as sincerely, he despised the mob. In other words: he adored and respected the people who abolished the Bastille and engaged in a fight for freedom and civic rights. However, when the fight for freedom turned into a ruthless drive for power and merciless revenge, the people became a mob. Freedom, equality, and fraternity changed into their opposites: terror, enslavement, and cruelty. “Be my brother or else I shall kill you,” said the Jacobins. And kill they did.

In The Red and the Black, Stendhal described a ball. At this magnificent ball, alongside Mathilde and Julien Sorel was also Count Altamira, a Neapolitan, a liberal sentenced to death in his homeland, and also a devout Catholic, a “bigot,” as labeled by Sorel. Let us turn to the conversation between Count Altamira and Julien Sorel. Says Altamira:

“Note that, in the revolution which I found myself leading…we failed only because I refused to have three heads cut off, and I would not distribute to our supporters seven or eight millions, deposited in a box to which I had the key. My king, who today is burning to grab me, and who before the revolt had been on first-name terms with me, would have given me the greatest medal in the land, had I cut off those three heads and handed out the money, because then I would have been at least half successful, and my country would have had a sort of constitution…. That’s how the world works, it’s all a chess game.”

“But then,” responded Julien, his eyes blazing, “you didn’t know how to play. Now…”

“You mean, now I’d cut off those heads, and I wouldn’t be the Girondin you made me out to be the other day?… I’ll answer you,” said Altamira sadly, “after you’ve killed a man in a duel, which is at least not so ugly as having him killed by an executioner.” “My Lord!” said Julien. “The man who desires a goal, also desires the way of accomplishing it. If I had any power, instead of being, as I am, a mere atom, I’d have three men killed if I could save the lives of four.”

His glance glowed with moral fire, and with contempt for men’s senseless decisions.

This dialogue is in reality Stendhal talking to himself. It is also a portion of the never-ending debate among people of the revolutionary and Napoleonic generation who cannot find their place in the new era. The time of heroism has passed and the past ideals have become only a troublesome decoration of real life. The heroes of yesterday must leave to make room for profiteers and rogues. The world of values gives way to the world of effectiveness.

Altamira was a liberal who headed the revolution against despotism or the revolution in the name of freedom. A revolution is an act of violence that, to a liberal from the prerevolutionary era, or from a time of former principles, may be justified only by the immediate abandonment of violence once victory is secured. Therefore Altamira, like Lafayette, did not cut off his enemies’ heads; he rejected violence; he did not want to kill. That is why he lost.

Julien Sorel, however, is not an aristocrat and a liberal who rejected despotism and chose freedom. Sorel is a plebeian who loves the revolution and Napoleon because they had their enemies beheaded. The emperor is truly his ideal. Sorel admires the “Little Corporal” for his parvenu talent, for his will to advance from the lower classes—a man who brings glory to France and becomes the ruler of the world. He also admires Napoleon for his ruthlessness in realizing these goals.

Advertisement

The chances created for the likes of Julien by the Revolution were cancelled by the Restoration. Energy and talent, diligence and courage—these were (until recently) tickets to success in history for the poor and those of low birth. The Restoration reserved everything for the old nobility and the new plutocracy.

Julien is pondering whether it is permissible, when faced with this blatant injustice, to reach for contemptible means like lies, hypocrisy, and violence:

“In fact,” he told himself, after meditating a long time, “if these Spanish liberals had compromised the people’s cause by committing crimes, they would not have been so easily swept away. These were arrogant children, and mere talkers…like me!” he suddenly exclaimed, as if waking with a start. “What difficult things have I ever done, to give myself the right to judge these poor devils, who in the end, once in their lifetimes, actually dared, actually started to act?… Who knows how you’ll deal with some grand deed, once it’s under way?”

Stendhal observed:

I confess that the weakness that Julien demonstrates, in this monologue, gives me a poor opinion of him. He’d be worthy of joining ranks with those parlor liberals, in their yellow gloves, who convince themselves they’re changing the whole way of life in a great country, but who can’t possibly have on their consciences the tiniest, most harmless scratch.

So says Stendhal the Jacobin. And Julien stands “admiring the great qualities of Danton, Mirabeau, and Carnot, who had known how to escape defeat.”

Julien meditates:

“A revolution cancels all a capricious society’s titles and distinctions. In a revolution, a man assumes whatever rank he earns by his behavior in the face of death…. What would Danton be today…? Not even a deputy attorney general… What am I talking about?…He’d be a government minister, because the great Danton, after all, did his share of stealing. Mirabeau sold himself, too. Napoleon stole millions, in Italy, and without that wealth, poverty would have stopped him in his tracks…. Only Lafayette never stole. Is stealing required? Is selling yourself inevitable?”

These are the dilemmas of Julien’s epoch. Can crime be annihilated with another crime? Or does that crime inevitably breed another crime?

One might think that giving up Jacobin terror and Napoleon’s wars for peace, though filled with intrigue, hypocrisy, and money, is not a bad exchange; in fact, it seems obviously a change for the better. After all, isn’t it better to live and slowly get rich than fear the guillotine or die at the Berezina? Well, isn’t it?

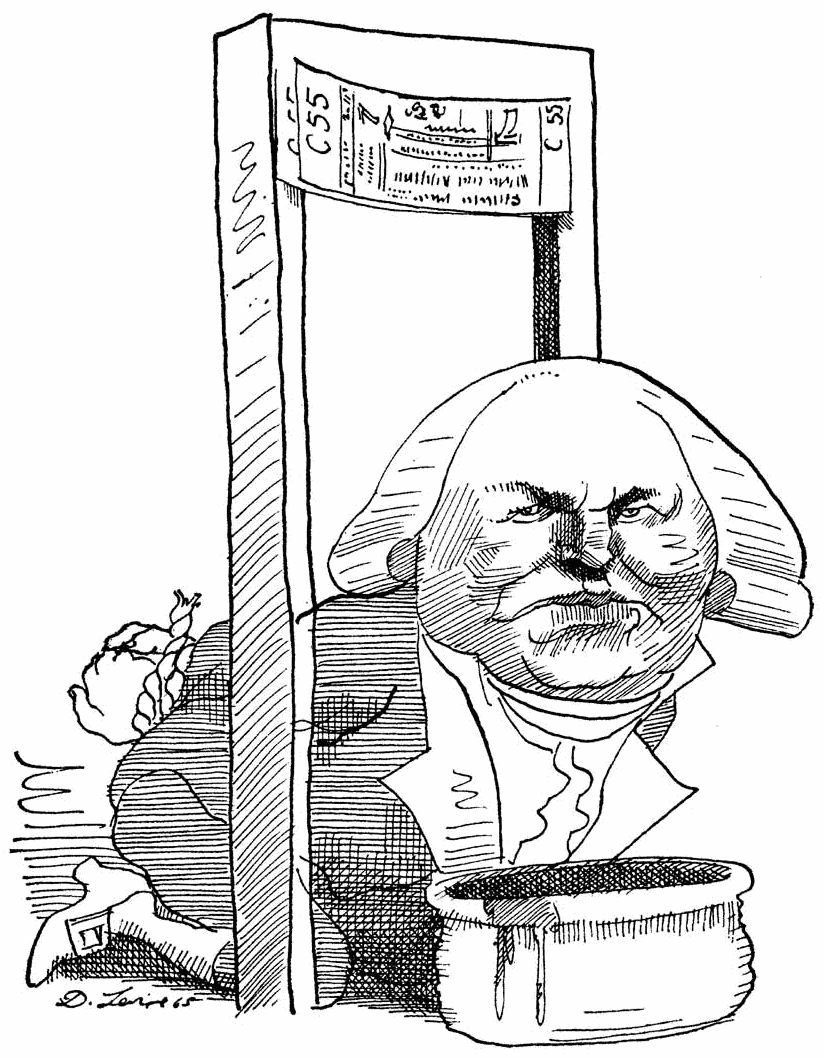

Agreed, but not in the case of Julien Sorel. His life experience was different. Julien never shook in his boots fearing the guillotine and never fought death while retreating from Moscow with Napoleon’s troops. For Julien, as for Karl Marx, the guillotine was a “strike of the hammer, which will obliterate all feudal ruins.” Napoleon’s wars were for him simply “a road to pride and glory.”

Julien is led by fury. It is the fury of Stendhal’s hopelessness and the fury of a plebeian grudge. This grudge, compounded by unfulfilled ambitions, gives birth to a hateful resentment of the world populated by people of auspicious beginnings and ample riches, the world of those successful in life.

Sorel perceived this world as a conspiracy against himself, and that is why he challenged it. His grudge is not unlike poisoning oneself with the virus of jealousy. Envy may lead to a career achieved unscrupulously. The insightful Lampedusa noted that the July Revolution of 1830 brought to power precisely such people: “take Thiers (the premier in 1836) who was a kind of Julien Sorel, but a Julien who refrained from the final shooting.”

However, bitterness did not stop Julien from “the final shooting.” The bitterness gave birth to the rebellion, which hit blindly. All of the French nineteenth century was a history of the grudge born of the bitterness of the Restoration, the era of the great disappointment, when grand ideas faded and turned into platitudes.

Consecutive plots, rebellions, and revolutions illustrated the immortality of Julien Sorel’s grudge. Young people, sentenced to poverty, degraded and begrudged, chose the road of a revolution that was to change the course of the world. Sorel’s contemporary Louis-Auguste Blanqui, a conspirator and revolutionary, admired by the people of the rebellion and hated by the people of success, declared that “a fight for life and death is on”: the united aristocracy of birth and money against the republicans and all the oppressed. A revolution is necessary as only it can “lighten up the horizon by cleansing the ground, and slowly take the curtains off, and open up the roads to a new order, …to a fundamental rebuilding of the society.” “It is necessary to shatter the existing state apparatus,” “dissolve the army and the judicial system,” “recall all functionaries on the higher and medium level,” “deport the clergy abroad,” take over property of the Church, abolish the existing penal code and the judiciary, and replace the bourgeois dictatorship with the dictatorship of the armed people.

Advertisement

That is the voice of Julien Sorel, who “refrained from the final shooting” by choosing the camp of the Revolution. It is hard not to relate to this boy of poor plebeian stock who did not want to accept his fate. The boy challenged the bad world in order to pursue his dream, until the very end. And what made that very end? The wise Stendhal found in Julien a cold look “showing a sovereign contempt.” He also found “a still unformed longing for vengeance of the most atrocious order. Who could deny,” asked Stendhal, “that such humiliating moments have given us the Robespierres of the world?”

Robespierre! The symbol of the Jacobin terror… When Danton was sentenced to the guillotine, a group of deputies demanded that he should be heard out. Robespierre rejected this demand with contempt, saying: “Who trembles now, is guilty.”

Blanqui is said to have had “a heart and mind filled with the purest love of the revolution.” They said the same about Robespierre—the Incorruptible. We shall always ask, however, how much of “the vague hope for the cruelest vengeance” was in the “purest love.” Sorel’s grudge bred that peculiar amalgamation that was the tragic experience of all the revolutions of the twentieth century. A begrudged rebellion and the need for vengeance changed a rebel into an executioner—the fate of the heirs of Robespierre and Danton, Julien Sorel and Auguste Blanqui, taught us that. Therefore, we listen very carefully to the words of the rebels who wish to turn everything upside down. And we closely watch their hands. We know all the sins and villainies of this world of ours. Sometimes Stendhalian fury grips us. We keep on trying to comprehend the mechanism of a creation of collective grudge that explodes in a blind rebellion.

We do know that every revolution breeds beneficiaries and the disappointed. The beneficiaries will praise the obvious benefits of the revolution: civic liberties and representative government, open borders and a press free of censorship, economic growth and a free market, new schools and universities, a flourishing banking system and the goodies of the stock exchange, a convertible currency and low inflation. The defeated and the bitter, the excluded and the degraded will curse this world and, perhaps, one more time will present their bitter bill—made out to us, the beneficiaries.

Right in front of our eyes, we can see the marching parade of corrupt hypocrites, thick-necked racketeers, and venal deputies. Everyday villainy, pompous lies, and spiteful intrigue seem to be better than ever. Today, in our world, there exists no great idea of freedom, equality, and fraternity. There is no Napoleon among us and there is no promise of a great glory. We no longer believe in the man of the moment. We have been effectively cured of the belief in absolute justice. But that does not mean we accept the universal mean trickery and absolute injustice. After all, a Julien Sorel still endures the humiliation, a grudge is still growing in his heart, together with the envy and hatred of the world of the beneficiaries—of our world. Is he dreaming about the guillotine and retaliation? Or is he waiting for some sign of hope?

Adapted from “Canaille, Canaille, Canaille!,” translated by Roman Czarny, which appears in Adam Michnik’s The Trouble With History: Morality, Revolution, and Counterrevolution, to be published by Yale University Press on May 27.