The conditions in which we read today are not those of fifty or even thirty years ago, and the big question is how contemporary fiction will adapt to these changes, because in the end adapt it will. No art form exists independently of the conditions in which it is enjoyed.

What I’m talking about is the state of constant distraction we live in and how that affects the very special energies required for tackling a substantial work of fiction—for immersing oneself in it and then coming back and back to it on numerous occasions over what could be days, weeks, or months, each time picking up the threads of the story or stories, the patterning of internal reference, the positioning of the work within the context of other novels and indeed the larger world.

Every reader will have his or her own sense of how reading conditions have changed, but here is my own experience. Arriving in the small village of Quinzano, just outside Verona, Italy, thirty-three years ago, aged twenty-six, leaving friends and family behind in the UK, unpublished and unemployed, always anxious to know how the next London publisher would respond to the work I was writing, I was constantly eager for news of one kind or another. International phone-calls were prohibitively expensive. There was no fax, only snail mail, as we called it then. Each morning the postino would, or might, drop something into the mailbox at the end of the garden. I listened for the sound of his scooter coming up the hairpins from the village. Sometimes when the box was empty I would hope I’d heard wrong, and that it hadn’t been the postino’s scooter, and go out and check again an hour later, just in case. And then again. For an hour or so I would find it hard to concentrate or work well. You are obsessed, I would tell myself, heading off to check the empty mailbox for a fourth time.

Imagine a mind like this exposed to the seductions of email and messaging and Skype and news websites constantly updating on the very instrument you use for work. In the past, having satisfied myself that the postman really had come and gone, the day then presented itself as an undisturbed ocean of potential—for writing (by hand), reading (on paper), and, to pay the bills, translating (on a manual typewriter). It was even possible in those days to see reading as a resource to fill time that hung heavy when rain or asphyxiating heat forced one to stay indoors.

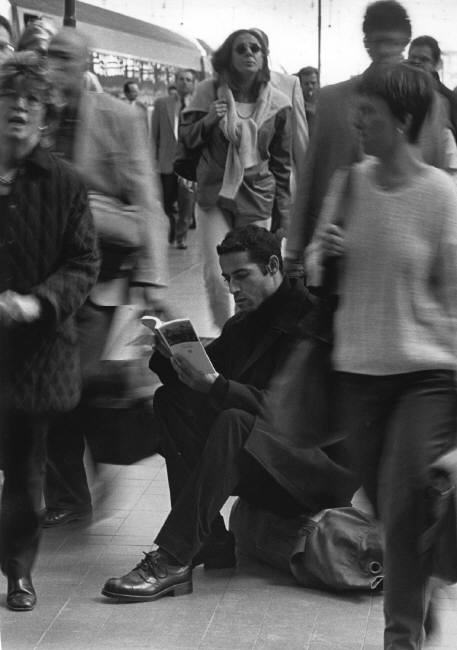

Now, on the contrary, every moment of serious reading has to be fought for, planned for. Already by the late 1990s, translating on computer with frequent connections (back then through a dial-up modem) to check email, I realized that I was doing most of my reading on my two or three weekly train commutes to Milan, two hours there, two hours back. Later, with better laptop batteries and the advent of mobile Internet connections, that space too was threatened. The mind, or at least my mind, is overwhelmingly inclined toward communication or, if that is too grand a word, to the back and forth of contact with others.

We all know this. Some have greater resistance, some less. Only yesterday a smart young Ph.D. student told me his supreme goal was to keep himself from checking his email more than once an hour, though he doubted he would achieve such iron discipline in the near future. At present it was more like every five to ten minutes. So when we read there are more breaks, ever more frequent stops and restarts, more input from elsewhere, fewer refuges where the mind can settle. It is not simply that one is interrupted; it is that one is actually inclined to interruption. Hence more and more energy is required to stay in contact with a book, particularly something long and complex.

Of course long books are still being written. No end of them. We have Knausgaard after all. People still sit on the subway with the interminable Lord of the Rings and all the fantasy box sets that now fill our adolescent children’s bookshelves. Certainly 50 Shades of Grey and its variously-hued sequels were far longer than they needed to be. Likewise Stieg Larsson’s Millenium Trilogy. Never has the reader been more willing than today to commit to an alternative world over a long period of time. But with no disrespect to Knausgaard, the texture of these books seems radically different from the serious fiction of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. There is a battering ram quality to the contemporary novel, an insistence and repetition that perhaps permits the reader to hang in despite the frequent interruptions to which most ordinary readers leave themselves open. Intriguingly, an author like Philip Roth, who has spoken out about people no longer having the “concentration, focus, solitude or silence” required “for serious reading,” has himself, at least in his longer novels, been accused of adopting a coercive, almost bludgeoning style.

Advertisement

Let’s remember just what hard work it can be to read the literary novel pre-1980. Consider this sentence from Faulkner’s The Hamlet:

He would lie amid the waking instant of earth’s teeming minute life, the motionless fronds of water-heavy grasses stooping into the mist before his face in black, fixed curves, along each parabola of which the marching drops held in minute magnification the dawn’s rosy miniatures, smelling and even tasting the rich, slow, warm barn-reek milk-reek, the flowing immemorial female, hearing the slow planting and the plopping suck of each deliberate cloven mud-spreading hoof, invisible still in the mist loud with its hymeneal choristers.

This is the kind of complexity one needs to work up to. Coming cold to it, on an early morning subway, for example, might not be ideal and would certainly lead to a different reading than if I arrive at it on the roll of what comes before. On the other hand, if I read mainly on public transport because these are the only moments when I’m not at a keyboard, I cannot really decide where to break off. I might be right at the flowing immemorial female when a voice announces Piccadilly Circus, or Times Square. Then when I restart I’ll have to figure out how much of a run-up I need, how far back I have to go, to tackle this waking instant again.

Going back further, here is Dickens in a single sentence in Our Mutual Friend:

Having found out the clue to that great mystery how people can contrive to live beyond their means, and having over-jobbed his jobberies as legislator deputed to the Universe by the pure electors of Pocket-Breaches, it shall come to pass next week that Veneering will accept the Chiltern Hundreds, that the legal gentleman in Britannia’s confidence will again accept the Pocket-Breaches Thousands, and that the Veneerings will retire to Calais, there to live on Mrs Veneering’s diamonds (in which Mr Veneering, as a good husband, has from time to time invested considerable sums), and to relate to Neptune and others, how that, before Veneering retired from Parliament, the House of Commons was composed of himself and the six hundred and fifty-seven dearest and oldest friends he had in the world.

The passage comes toward the end of this eight-hundred-page novel. All kinds of previous references have to be kept in mind and some knowledge of the English parliamentary system and the jargon of the time is essential. Dickens is a world to immerse yourself in for periods of not less than half an hour, otherwise the mind will struggle to accustom itself to the aura of it all and the constant shift between different voices and rhetorical ploys. It is so endlessly playful.

Returning to the twentieth century, here, for connoisseurs of suicidally elaborate prose, is Henry Green describing a graveyard in his novel Back:

For, climbing around and up these trees of mourning, was rose after rose after rose, while, here and there, the spray overburdened by the mass of flower, a live wreath lay fallen on a wreath of stone, or on a box in marble colder than this day, or onto frosted paper blooms which, under glass, marked each bed of earth wherein the dear departed encouraged life above in the green grass, the cypresses and in those roses gay and bright which, as still as this dark afternoon, stared at whosoever looked, or having their heads to droop, to grow stained, to die when their turn came.

Coming as it does on the opening page, this sentence amounts to a stern warning not to imagine that this book can be picked up and put down lightly. There are sentences in Green’s work that seem to mesmerize the mind and invite three or four readings before moving on. Set aside some quiet time for me, Green is protesting. Let’s move into an entirely different frame of mind.

“In a good novel—it hardly needs to be said—every word matters.” Thus Jay Caspian Kang giving us the lit-crit, text-is-sacred orthodoxy in a recent New Yorker blog post. Honestly, I wonder whether this was ever really true; authors have often published then republished their work with all kinds of alterations but arguably without greatly changing a reader’s experience (one thinks of Thomas Hardy, Lawrence, Faulkner), while many readers (myself included), in the long process of reading a substantial novel, will simply not register this or that word, or again will reread certain sections when they’ve lost their thread after a forced break, altering the balance of one part to another, so that we all come away from a book with rather different ideas of what exactly it was we experienced during perhaps a hundred hours of reading.

Advertisement

But today Kang’s claim seems less and less likely to be true. I will go out on a limb with a prediction: the novel of elegant, highly distinct prose, of conceptual delicacy and syntactical complexity, will tend to divide itself up into shorter and shorter sections, offering more frequent pauses where we can take time out. The larger popular novel, or the novel of extensive narrative architecture, will be ever more laden with repetitive formulas, and coercive, declamatory rhetoric to make it easier and easier, after breaks, to pick up, not a thread, but a sturdy cable. No doubt there will be precious exceptions. Look out for them.