When the jihadists of ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) tweeted pictures of a bulldozer crashing through the earthen barrier that forms part of the frontier between Syria and Iraq, they announced—triumphantly—that they were destroying the “Sykes-Picot” border. The reference to a 1916 Franco-British agreement about the Middle East may seem puzzling, coming from a radical group fighting a brutal ethnic and religious insurgency against Bashar al-Assad’s Syria and Nouri al-Maliki’s Iraq. But jihadist groups have long drawn on a fertile historical imagination, and old grievances about the West in particular.

This symbolic action by ISIS fighters against a century-old imperial carve-up shows the extent to which one of the most radical groups fighting in the Middle East today is nurtured by the myth of precolonial innocence, when the Ottoman Empire and Sunni Islam ruled over an unbroken realm from North Africa to the Persian Gulf and the Shias knew their place. (Indeed, the Arabic name of ISIS—al-Dawla al-Islamiya fil-Iraq wa al-Sham—refers to a historic idea of the greater Levant (al-Sham) that transcends the region’s modern, Western-imposed state borders.)

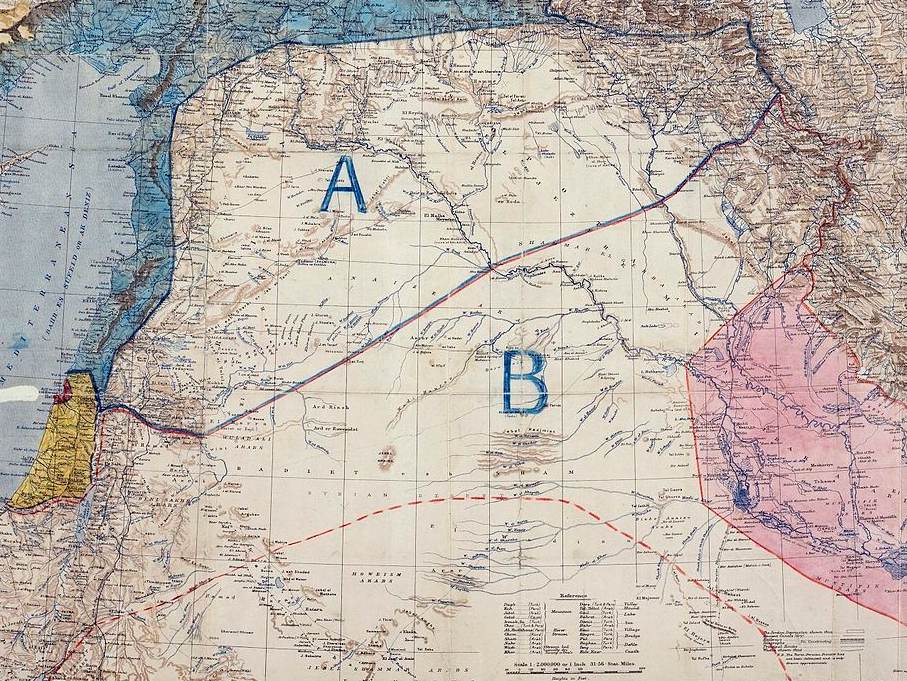

But why is Sykes-Picot so important? One reason is that it stands near the beginning of what many Arabs view as a sequence of Western betrayals spanning from the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire in World War I to the establishment of Israel in 1948 and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The Sykes-Picot agreement—named after the British and French diplomats who signed it—was entered in secret, with Russia’s assent, in May 1916 to divide the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire into British and French “spheres of influence.” It designated each power’s areas of future control in the event of victory by the Triple Entente over Germany, Austria, and their Ottoman ally. Under the agreement Britain was allocated the coastal strip between the Mediterranean and the river Jordan, Transjordan and southern Iraq, with enclaves including the ports of Haifa and Acre, while France was allocated south-eastern Turkey, northern Iraq, all of Syria and Lebanon. Russia was to get Istanbul, the Dardanelles, and the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian districts.

Under the 1920 San Remo agreement, which built on Sykes-Picot, the Western powers were free to decide on state boundaries within these areas. The international frontiers—with Iraq’s framed by the merging of the three Ottoman vilayets of Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra—were consolidated by the separate mandates granted by the League of Nations to France in Lebanon and Syria, and to Britain in Palestine, Transjordan, and Iraq. The frontier between French-controlled Syria and British-controlled Iraq included the desert of Anbar province that was bulldozed by ISIS this month.

Kept hidden for more than a year, the Anglo-French pact caused a furor when it was first revealed by the Bolsheviks after the 1917 Russian Revolution—with the Syrian Congress, convened in July 1919, demanding “the full freedom and independence that had been promised to us.” Not only did the agreement map out—unbeknownst to the Arab leaders of the time—a new system of Western control of local populations. It also directly contradicted the promise that Britain’s man in Cairo, Sir Henry McMahon, had made to the ruler of Mecca, the Sharif Hussein, that he would have an Arab kingdom in the event of Ottoman defeat. In fact, that promise itself, which had been conveyed in McMahon’s correspondence with the Sharif between July 1915 and January 1916, left ambiguous the borders of the future Arab state, and was later used to deny Arab control of Palestine. McMahon had excluded from the proposed Arab kingdom “portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo [that] cannot be said to be purely Arab.” This clause led to lengthy and bitter debates as to whether Palestine—which Britain meanwhile promised as a homeland for Jews under the terms of the November 1917 Balfour Declaration—could be defined as lying “west” of the vilayet, or district, of Damascus.

In his 1922 white paper, Winston Churchill insisted that “the whole of Palestine west of the Jordan was excluded from Sir Henry McMahon’s pledge,” but Arab writers, including George Antonius, argued with forensic precision that Palestine was not among the exclusions specified and agreed to in the Hussein-McMahon correspondence. Antonius’s argument was strengthened by the fact that successive British governments refused to publish the correspondence, on public-interest grounds. The poorly drafted and geographically imprecise commitment McMahon had made to the Arab leader was too embarrassing to be exposed to public scrutiny until 1939, after Antonius had produced his version of it (translated from Arabic sources) in his 1938 book The Arab Awakening.

Advertisement

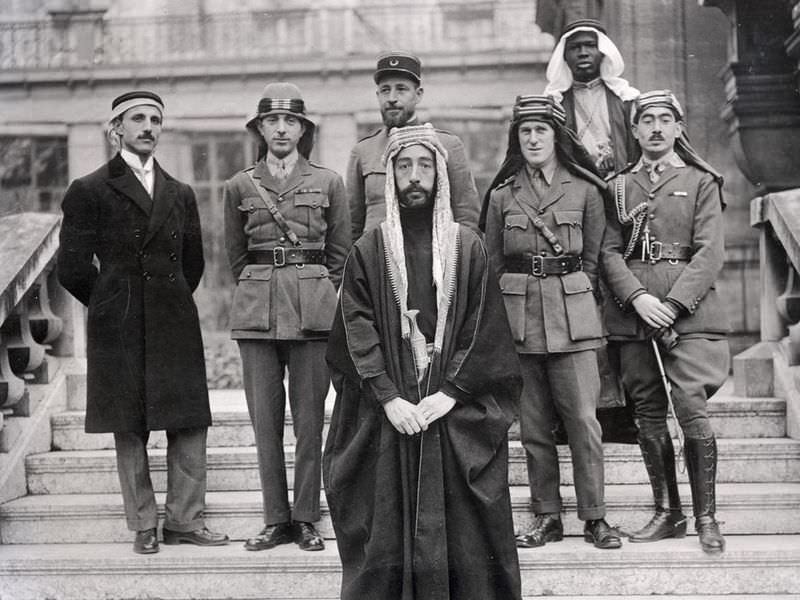

Pardoxically, even as the Sykes-Picot agreement was reached, a different vein of British policy was unfolding that aimed at liberating the Arab Middle East, though under British guidance. The British had been installed in Egypt since 1882, and had long pursued a dream of Arab unity—hence their interest in encouraging the Sharif of Mecca, whose sons Faisal and Abdullah led the Arab revolt against the Turks. In fact, the British “Arabists,” including McMahon and Sir Gilbert Clayton, head of Military Intelligence in Cairo, and the redoubtable T.E. Lawrence, took a commanding role in the liberation of the Arab provinces, encouraging the establishment of local governance in ways that contradicted the Anglo-French agreement. As the British army swept up from Egypt through Syria, it refrained from entering the larger towns, allowing Faisal and his forces to occupy them to maintain the momentum, and legitimacy, of the Arab national movement. The conquest of Damascus by the British in October 1918 was the outstanding example. As the Israeli scholar Eyal Zisser points out: “The aim was to create a situation in which these towns and areas could be characterized as liberated by the Arabs, who would then have a rightful claim.”

Sir Mark Sykes, the Middle East advisor to the secretary of state for war, Lord Kitchener, who signed the Sykes-Picot agreement with the French diplomat François-Georges Picot, was somewhat Francophile in comparison with the “Arabists,” who he thought were in danger of alienating the French. In view of the devastation the French were suffering on the Western Front (with the loss of a million men more than the British), compounded by the failure of the Gallipoli campaign, Britain, he felt, had a compelling need to humor its French ally. France could claim historical interests in Greater Syria stretching back to the sixteenth century and point to the protection that it had granted Lebanon’s Maronites in 1649. This protection was activated in 1860, when the French sent 6,000 troops to defend the Maronites when large numbers of them were being slaughtered in a civil war with the Druzes.

In the event, the Arabists’ hope for an independent Arab kingdom under British tutelage was trumped by French ambitions. It may be particularly telling that Mosul, the Iraqi city that has just been captured by ISIS and like-minded Sunnis from the US-backed Maliki government, was also a pawn in this earlier colonial struggle between France and Britain. In the course of the murderous and costly Mesopotamian campaign against the Ottoman army (1915–1918) the British had installed themselves in Iraq, and on a visit to London the French leader George Clemenceau conceded that the British should have Mosul, and a free hand in Palestine (which was supposed to be international under the Sykes-Picot terms), with the French acquiring the German stake in what became the Iraqi Petroleum Company.

Though Lawrence took Faisal to the Paris peace conference in 1919, and arranged for him to meet British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, his plan for an Arab kingdom based in Damascus was doomed. In July, 1920, four months after Faisal was made King of Syria in March, the French took over Damascus, expelled him, and imposed a form of direct rule that lasted till the British arm—with token Free French forces—removed the colonial Vichy government in 1941. British claims that French control in Syria violated that Sykes-Picot concept of “spheres of influence” in the Arab areas were undermined by the degree of control the British were exercising in Palestine, Transjordan, and Iraq (where Faisal from 1921 was able to rule as king under British Mandate rule).

By formally abolishing the Syrian-Iraqi border ISIS doubtless hopes to evoke memories of the Ottoman era before supposedly artificial states were constructed for the convenience of European powers—a time when frontiers were porous and the ways of Islam were universally observed. The fatal flaw in this utopian vision—apart from its obvious historical inaccuracy—is its failure to recognize the division between Sunnism and Shiism that long predated Western interventions in Iraq and Syria. Indeed, Iraqi tribes, traditionally hostile to government, began adopting Shiism in large numbers during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. However much the leaders of ISIS seek to draw on the imagery of an international Arab jihad rolling back a century of Western imperialism, the growth of ISIS feeds on these sectarian tensions that have been reanimated across the region. Politically, the jihadists have gained support from the widespread hatred of the Shiite cronyism of the Maliki regime, which replaced the cronyism of Saddam Hussein’s, as well as from the brutality of its counterpart in Damascus. And to the extent that foreign powers are driving the situation, the underlying dynamic flows less from the West than from the rivalry between the Sunni monarchies of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf on one side and Shiite Iran on the other.

Advertisement