“The only thing that interests me is man and his suffering,” declares French cartoonist Jacques Tardi in the foreword to his It Was the War of the Trenches, “and it fills me with rage.” The book that follows—a series of delicately drawn, thoroughly researched, thoroughly grim vignettes of life in the trenches during World War I—bears him out. Tardi’s war does not unfold linearly, nor, although it sticks to the French troops, does it give us a distinct set of characters to follow. Instead, it skips from soldier to soldier and year to year, starting with a series of artillery barrages (“The muzzles of the cannons turn red hot and their servants go deaf”) in late 1917, then turning back to the outbreak of war in 1914 (an old man is beaten to death in a cafe for refusing to sing La Marseillaise, “one of the first victims of the war”), then ahead again to a French infantry charge at an unspecified battle in 1916, and on, crabwise, from there.

It’s a war not of progression or strategy, but of madness and agony, told in fragments. The Germans advance using civilians as shields, and the French fire anyway. A company struggles back to the trenches after a charge has ended in devastating failure and is shelled by its own general—for “cowardice.” A cook’s attempt to deliver soup and wine to his trenchmates becomes a night-long, thirteen-page journey through hell, featuring a suicide by hand-grenade, a tumble into “mud” made of disintegrating corpses, and the dying confession of a fed-up soldier who’s been murdering military police and is caught in a shelling.

Published in France in 1993, It Was the War of the Trenches was finally translated into English in 2010 by the late, influential Fantagraphics publisher Kim Thompson. Along with Tardi’s later book about the war, Goddamn This War! (2008-2009; translated by Thompson in 2013), it is one of the most passionately bleak works in the history of comics. Tardi is unremitting in his focus on the small, human details of the catastrophe—not just the look of uniforms and weaponry, but the way one soldier advances in an awkward, stiff-armed posture, “protecting my belly with the butt of the rifle,” and the way another makes sculptures and rings from discarded shells, to sell to his comrades. The closest thing to a panoramic view comes from the beleaguered cook: “Amazing how much harm it was possible to inflict on men and beasts,” he reflects, gazing at a dead horse lodged in a tree. “On men, fine, it was their war after all.”

This is not exactly a joy to read, to be sure. (Tardi himself found the book “exhausting” to make, and produced it in dribs and drabs over the course of a decade.) What pulls you along is the liveliness and authority of Tardi’s style. No matter the subject, his line is immediately recognizable: clear and solid, but also loose, even casual. He tightens up a bit to render the details of architecture, machinery, or clothing, then indicates a distant tree or a reflection in a puddle with a simple well-placed scribble. His depiction of a captain’s trench quarters, midway through It Was the War, is typically confident. The sandbags above the entrance, the kerosene lamp hanging from the low ceiling, the crucifix and family photos on the wall, the contrast between the captain’s kempt moustache and relaxed posture and the scruffy weariness of a sergeant reporting to him—all this is drawn with immediacy and precision, but without any fussiness; the Christ on the crucifix is little more than an oblong blob, the light from the lamp just a speckling of white.

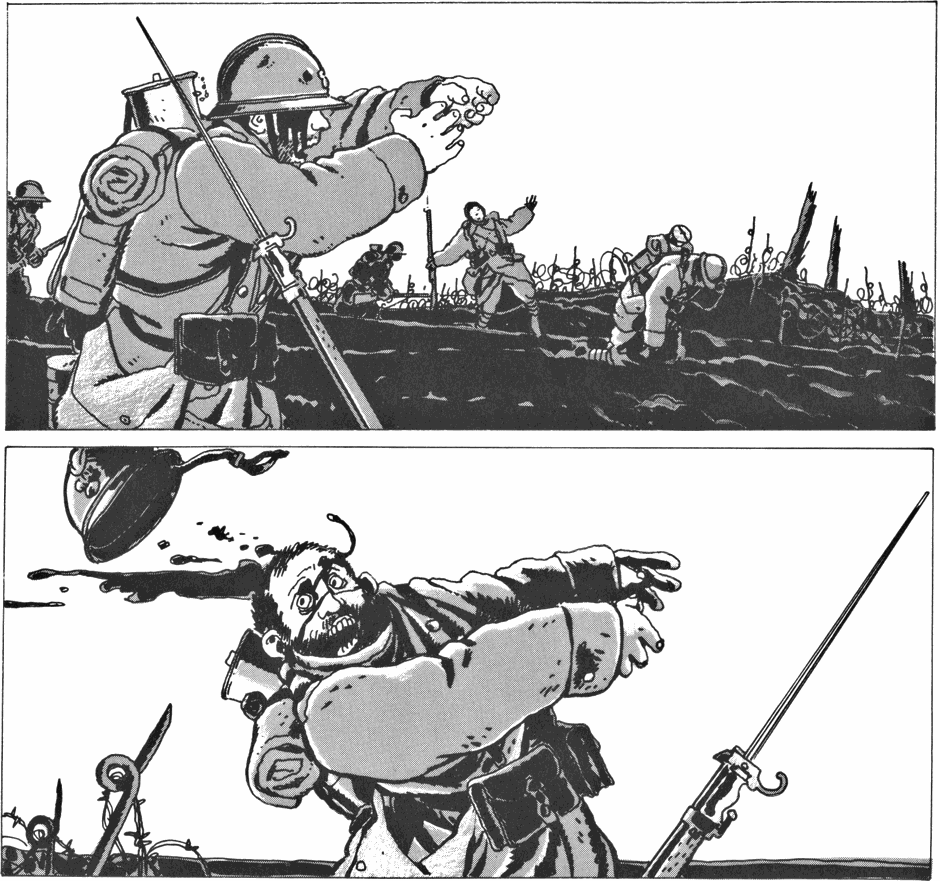

On Tardi’s page, the world has weight. Clothes wrinkle and drape, get wet and drag the wearer down; objects topple, shatter, rot. The Tardi man is solid, stolid, world-weary; his shoulders are slumped, his hands thick-fingered and lumpy, his face wide-nosed, heavy-browed; he lugs, he bends, he squints through the smoke of his cigarette. I’m sure there’s a dancing scene or two in Tardi’s oeuvre, but it’s hard to picture. (At one point in Goddamn This War!, a young soldier lets out an entirely carefree grin, and it looks like it was drawn by someone else.) Violence and gore, when they come, are all the more shocking for the way they break this heavy world apart. The drawing becomes rough and violent, blobs and dots and squiggles strewn across the page. A shell goes off in a graveyard and the explosion is a wash of black and white smudges, with bodies flying through it; a corpse in a trench has a head that is half carefully rendered face, half smear of ink.

Advertisement

Since the late 1960s, Tardi has had a multifarious, wildly productive career, drawing everything from light-hearted science fiction to family memoir to adaptations of the crime novels of Jean-Patrick Manchette (the third and last of these, Run Like Crazy Run Like Hell, is due out in English this winter). His style has shifted a little with each—especially bare and scratchy for the intimate nihilism of his Manchette adaptations, especially slick for the nostalgic clutter of the ongoing Extraordinary Adventures of Adele Blanc-Sec, his gleefully cynical (and extremely popular) historical adventure series.

For his WWI books he restricts himself almost exclusively to three horizontal panels per page. These unusually wide, large panels fit the trenches and barren battlefields, and give him room to balance his careful renditions of tanks, guns, soiled uniforms, and exhausted faces against the emptiness of washed-out sky or devastated ground. The three-panel page also gives the action a slow, stuttering rhythm—a series of frozen moments, rather than any sort of continuous movement. This suits the mournful anecdotes of It Was the War perfectly. A pointless French infantry charge early in the book is agonizing, monumental. The soldiers are running, stumbling, bleeding, but with an eerie, almost sadistic slowness; Tardi draws them just at the moment they fall, in one case right as the bullet hits. The fundamental trick of comics is to convince us that a series of still images, all visible at once, are in fact depicting the passage of time. At its best, It Was the War manages to do the reverse: we see furious action stilled, the final horrible moments of these men prolonged indefinitely. The captions offer us a taste of contemporary jingoism: “Joyful, despite their grief, are those families whose blood flows for their country.”

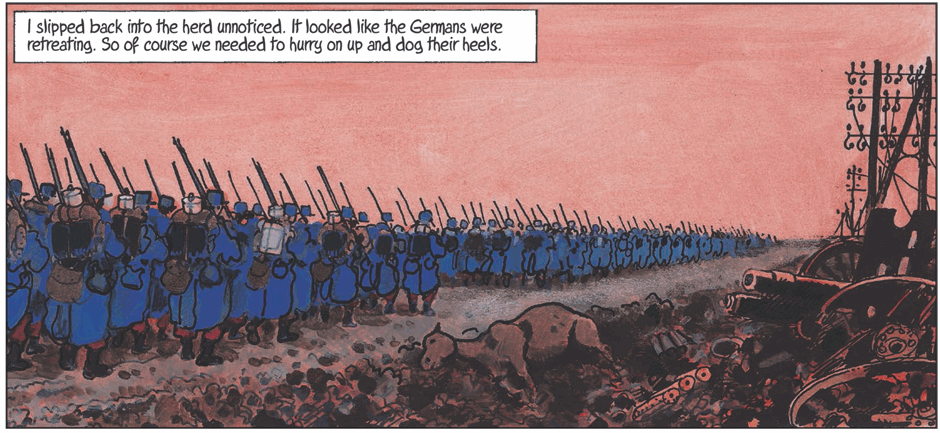

Published some fifteen years after its predecessor, Goddamn This War! is less effective. The earlier book’s hodgepodge of stories is replaced by a linear retelling of the entire war—from the troops marching out of Paris in the summer of 1914 to the immediate aftermath of the war in 1919— through the eyes of an army everyman. It is in large part a series of static tableaux, stitched together with extensive, rather generic narration: “The kids loved seeing us heroes troop by…. The experts in the General Staff had assured us: Germany would respect Belgium’s neutrality”; or, more emotively but no more memorably: “So much human meat was needed to satisfy the insatiable appetites of Europe’s masters.” At times the compositions are surprisingly stiff—one can feel the historical photographs Tardi used for reference lurking just off-page (indeed, some of these photos are included in a chronology of the war by historian Jean-Pierre Verney at the end of the book).

But Goddamn This War! does bring a surprising beauty to the horrors it depicts. It Was the War has a grimy, muted palette of black, white, and flat grays, in some cases scratched up to make them a little nastier (Tardi has spoken of how much he enjoyed the “sensual work” of doing this by hand). Goddamn This War!, though, is in full painted color, perhaps taking advantage of the improvements in printing technology since the first book. There’s a nostalgic ache to the bright reds and blues of the uniforms in the opening pages, as the war is starting, and a real sense of gloom to the way more muted colors take over the rest of the book. A panel showing the results of an artillery barrage is so thoroughly violent it is barely legible, and all the more shocking for the way its red-orange gore contrasts with the subdued blues and grays of trench-life on the rest of the page.

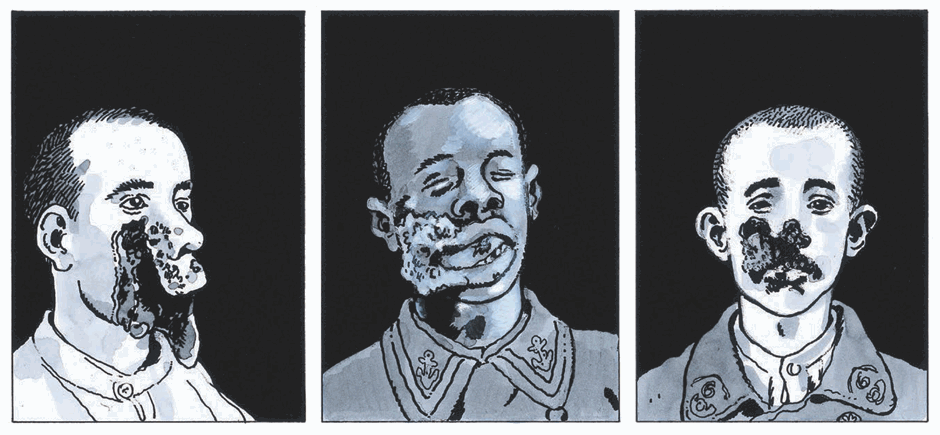

Goddamn This War! also contains one moment of genuine brilliance. It is near the end of the book, with the signing of the armistice already announced (over a drawing of a French and a German soldier reclining in corpse-strewn no-man’s land). Tardi breaks from his horizontal layout for two wordless pages of portraits, nine portraits per page, of the so-called gueules cassées, severely disfigured survivors. The drawings are sensitive, distinctive, just realistic enough. Here the obvious use of photographic references is much of the point. These panels not only ask us to look at these disturbing images, to imagine the lives they represented, but also record Tardi’s own much more extended attention, the hours and days he spent drawing them, the years it took him to make these books. It’s a silent, unmistakable argument—that a hundred years on, this is what is worth remembering from the war. Not the generals or the politicians or the lines on a map, but these faces, and what was done to them.

Advertisement

Jacques Tardi’s It Was the War of the Trenches and Goddamn This War! are now available from Fantagraphics Books. A combined edition, Tardi’s WWI, will be published in November.