I was twelve years old when I saw my first Peter Brook production, and the effect of entering his concentrated world, of experiencing the actors as a personal presence, of feeling myself to be part of a spectacle rather than the watcher of one, has never left me. It remains an artistic ideal: spare, attentive, incendiary, mystical.

The play was Marat/Sade (1965) by Peter Weiss, or, in its full title: The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of Marquis de Sade. Residents of an insane asylum, each with his own malady—somnambulism, priapism, schizophrenia, mania—play the roles of historical figures of the French Revolution. The director of this play within a play is the Marquis de Sade, who is also an inmate at the asylum.

I had no knowledge of Antonin Artaud’s theories of stirring the subconscious in theater or of Bertolt Brecht’s insight that we become closer to a performance by being emotionally removed from it (because it provokes us to analyze the action rather than slump into a cushion of suspended disbelief and illusion). I had no idea that what I was beholding was a melding of these two ideas, with a third element that may be called Peter Brook’s sensibility—his gift for establishing a flow between performers and audience, his belief that “if something has happened, it has happened between us.” What happened between us, for my part, was the shock that ideas and emotion, history and extravagant acts of madness, were all part of the same human hurricane and could be encompassed in a single work of art.

Peter Brook has directed at least fifty plays since Marat/Sade, and his latest, The Valley of Astonishment, is currently playing at Theater for a New Audience’s Polonsky Shakespeare Center in Brooklyn. Though a relatively minor production, it immediately plunges you into the pool of his sensibility. Like his 1995 play The Man Who, which was inspired by Oliver Sacks’s book of neurological case studies, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, it is a meditation on the vagaries and tricks of an aberrant brain. The inspiration this time is A.R. Luria’s psychological study of Solomon Shereshevsky, a failed journalist whose memory, according to Luria, had “no distinct limits.” With perfect accuracy Shereshevsky could repeat back long sequences of unrelated words, backwards or forwards. Without advance notice, he could do it again fifteen years later.

Integral to this extraordinary memory was Shereshevsky’s severe case of synesthesia, the mismatch of senses, where sound evokes color, objects evoke taste, and touch turns into an odor. “What a crumbly, yellow voice you have,” Shereshevsky told one of Luria’s colleagues while conversing with him. For him, the number seven was “a man with a moustache and the number eight “a very stout woman.” Eighty-seven was “a fat woman and a man twirling his moustache.” He could count into the thousands in this manner. The fact that it defeated the purpose of a logical numerical system was beyond him.

Shereshevsky could not categorize, generalize, or think abstractly. But most important, he could not forget. “You can’t study a memory. It has no length, no shape,” says Sammy Costa (played by Kathryn Hunter), a journalist in her mid-forties who is Brook’s contemporary New York stand-in for Shereshevsky. Of course, this isn’t strictly true. Memory comes with synaptic sparks, lit-up neurons, a small fire observable in the brain. Forgetfulness, on the other hand, slips in stealthily, like a soft wind, shrouded in mystery. What is there to observe when neurons fail to ignite and nothing happens? This failure to ignite never occurs in Shereshevsky’s (or Sammy Costas’s) brain.

Neither the fictional nor the real Shereshevsky could conceive of the word nothing. “I thought it would be better to call nothing something…for I see this nothing and it is something… That’s where the trouble comes in,” Shereshevsky told Luria. Sammy Costas conceives of nothing as “a pale cloud of steam.” This is the most moving aspect both of the real life and the one on stage. In an attempt to halt the tide of her memory, Costas writes down her memories and burns the paper (as did Shereshevsky). “How do I get rid of all this rubbish?” she asks. It is a pathetic hope that what can be burned to ash on the outside can be obliterated within as well.

In The Valley of Astonishment, the burning of the paper is mimed, but it immediately threw me back to the real fire Brook built on stage in his magisterially pared-down version of La Tragedie de Carmen (1981). In Carmen the players light a campfire at nightfall, a brief respite from the turmoil that has transpired and the turmoil that is to come. In The Valley of Astonishment, Costas’s fire would (if it could) give her a momentary reprieve from the turmoil of her brain.

Advertisement

Brook is less concerned with Costas’s disorder itself than with its effect on her as a human being. He doesn’t want us to behold the spectacle of Sammy Costa but to imagine what it would feel like to be her. In a way, her disorder harkens back to the asylum inmates in Marat/Sade who are also afflicted with one form or another of sensorial aberrance. It is part of Brook’s genius that almost everything he creates seems to flow into a single work.

The staging of Valley of Astonishment could not be simpler: two musicians, three actors, and a set of three or four identical pine or balsam chairs. The actors continuously change role and style of being. Midway through the play, the Luria-like psychologist who studies Costas does a comic, manic turn as a huckstering magician; he is one of the acts in a low-rent variety show that Costas joins as a mnemonist (as did the real-life Shereshevsky).

The new home of Theater for a New Audience in downtown Brooklyn is sleek and spare, a theater in the square with seats on three sides, perfect for Brook’s purposes, because the stage resembles a public plaza, a shared space between performers and audience. Brook is no fan of the proscenium stage, a divided space, with the actors and lights on one side and the audience on the other. (I have, however, seen him use it to powerful effect, in a production of Hamlet at the Harvey Theater at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, which took place in the restricted space of a small carpet laid on stage, and at the pre-renovated Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center, where Carmen was performed.) Brook also takes a dim view of outdoor performances. He believes that “the best theater is enclosed, because then you have the possibility of concentration.”

Kathryn Hunter, slight, commanding, clad in black, and with a voice like crushed glass, is a bewildered Costas, more confused by her diagnosis than her ailment. She had thought she was normal until she was told she was not, and that is where her troubles began. All the actors are initiates of the Peter Brook manner of imbuing gesture and utterance with an element of awe. One of Brook’s achievements is that his work rarely feels stylized or forced. You don’t think of a Brook play as “experimental theater,” because unlike the work of other avant garde directors, it feels natural. If at times it seems magical, that isn’t because it employs magic, but because of the level of attention it provokes.

Woven into The Valley of Astonishment are passages from the poem The Conference of the Birds by the twelfth-century Sufi poet, Farid ud-Din Attar. Almost forty years ago, Brook turned the poem into a play, and took it to Saharan Africa, with Helen Mirren and others, in an attempt to see if he could create a theater that did not depend on having a common culture or language. The poem tells the story of a gathering of birds who embark on a quest for enlightenment with the pretext of searching for their king.

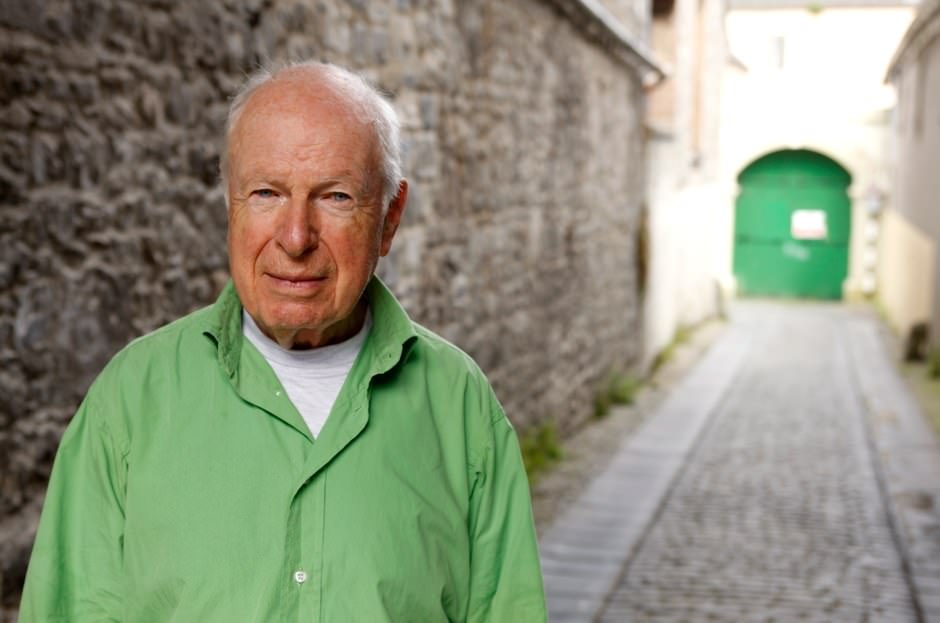

After the performance of The Valley of Astonishment that I attended, Brook, who will turn ninety next year, hobbled onto the stage in a lime green shirt, a shining black lycra vest, black jeans decorated with a small English flag, and sneakers. He told the audience that the reason he used the poem was “to remind us of the mystery of being human.” He added, “This is the endless, eternal role of theater, to touch a degree of compassion, to bring about an understanding that one never has.”

“When all is gone,” says Sammy Costas in the last line of the play, “pay attention to the secret drop of rain.”

Peter Brook and Marie-Hélène Estienne’s The Valley of Astonishment is playing at Theater for a New Audience in Brooklyn through October 5.