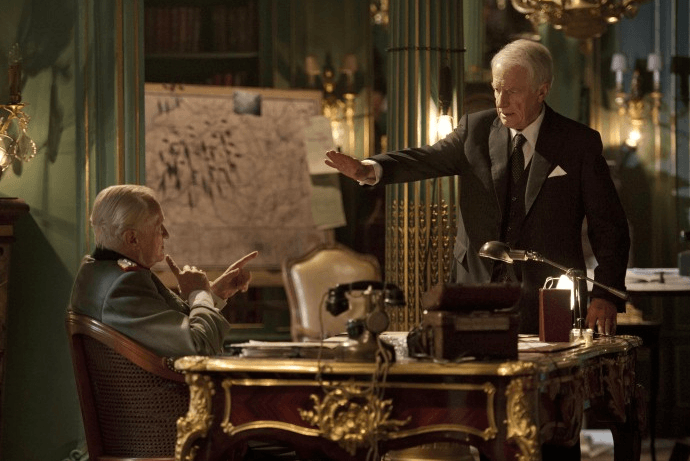

In his new film Diplomacy, Volker Schlöndorff has expertly created the creepy, almost surreal atmosphere of two men discussing the ruination of Paris while sitting in Louis XVI chairs, a fine claret readily at hand, watching the dawn over the city through the elegant windows of the room where Napoleon III once entertained his mistress.

Diplomacy is a film of a French play (by Cyril Gély) about a legend. In the movie, as in the play, the chaotic last days of Paris under German occupation in August 1944 are condensed into one night, which the two main historical characters—General Dietrich von Choltitz, military governor of Paris, and the Swedish consul Raoul Nordling—spend playing a kind of verbal game of chess at the Hôtel Meurice on the Rue de Rivoli.

The stakes of their game could not be higher: the survival of Paris. Von Choltitz is a plump Prussian general of the old school, played brilliantly by the French-Danish actor Niels Arestrup. Dispatched to France to become the final German military governor of Paris in the summer of 1944, he carried with him Hitler’s order not to surrender Paris to the Allies under any circumstances. The Germans would fight to the last man and leave the city in ruins. Since the German defeat is already certain, von Choltitz has little choice but to prepare for the capital’s destruction, its bridges, its museums, its churches, and even the Eiffel Tower. The silver-tongued Swedish diplomat, acted with equal panache by André Dussollier, has to try to talk him out of it.

Nordling does his best to convince the German aristocrat—who speaks elegant French in the film—that he cannot afford to go down as the man who blew up Paris. It would be a crime not only against humanity, but against civilization, and wreck for many centuries any chance of French reconciliation with Germany. Von Choltitz resists by claiming that he cannot defy Hitler’s orders. He is, after all, a soldier, and besides, his family back in Germany would be harmed if he betrayed the Führer. But when the general, who is quite aware of Hitler’s folly, is assured by the diplomat that his family will be safe, since he, Nordling, will personally make sure they will be smuggled across the border to Switzerland by the resistance, he agrees to save Paris.

It is clear at the end of the film that Nordling had no intention of helping von Choltitz’s family, but what is a little lie when the most beautiful capital in the world is preserved? This beauty is hinted at, caught in glimpses, as it were, through the hotel window, almost like a mirage, which makes the horror of its imminent destruction even more poignant than simple shots of the city’s famous landmarks would have done.

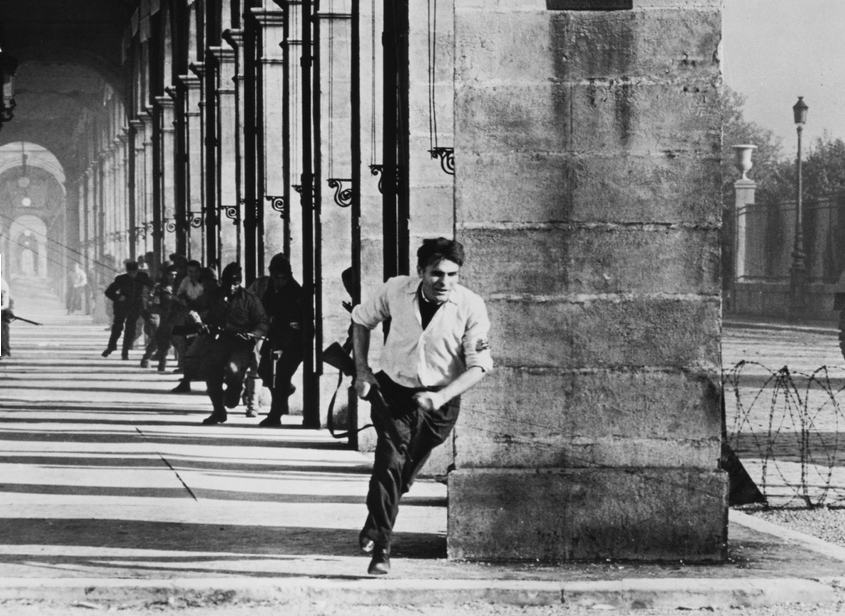

Even though Diplomacy has not quite shaken off the air of a theatre play, it is an alluring story, beautifully dramatized and acted. The film does not depict the German general as a hero, but more as a deeply flawed character who did the right thing in the end. But why? The notion that he acted out love for Paris or defied Hitler because he knew he was mad, was promoted largely by the general himself in his memoirs, entitled Is Paris Burning (1951). That book inspired an earlier film about this story, René Clément’s Is Paris Burning (1966), in which Orson Welles played Nordling (and resembled him much more than Dussollier) and Gert Fröbe, the stereotypically Hollywood German, von Choltitz, whose piggish looks he shared a great deal more than Niels Arestrup.

Unlike the earlier film, Schlöndorff and Gély, who wrote the script of Diplomacy, don’t entirely follow the general’s self-aggrandizing account, hence the story of his wishing to save his family. But it is hardly credible that von Choltitz would have trusted a Swedish diplomat with the fate of his wife and children, especially when their lives would depend on a promise of derring-do by a shadowy bunch of resisters. As actual fact, they were saved by the turmoil in Germany, which allowed them to keep their heads down. After surrendering to French resistance forces in late August, 1944, the general was turned over to Allied forces. In 1947, he was released from captivity, spent in the relatively confortable confines of a senior officers’ POW camp outside London, and then Camp Clinton, Mississippi.

The problem with both movies lies in the legend. For much of Diplomacy is fiction. There was no all-night conversation between the German and the Swede. The fate of von Choltitz’s family was never the issue. Hitler did not, as suggested in the earlier film, phone von Choltitz screaming: “Is Paris burning?” (He might have bellowed this at another general, Alfred Jodl.) In any case, whatever Hitler’s wishes might have been, the Germans in August 1944 didn’t have the wherewithal to destroy Paris in the way they blew up Warsaw later that year.

Advertisement

This much is known: Nordling did meet von Choltitz several times, mainly to arrange the release of French political prisoners, and to negotiate a truce (threatened by the Communist resistance as much as by German zealots). We also know that von Choltitz, however aristocratic in his comportment, had been a very ruthless character, responsible for the destruction of the center of Rotterdam in May 1940. Worse that that, in 1942 his regiment flattened Sevastopol, and von Choltitz faithfully carried out orders to “liquidate” the Jewish population. He was a perfect illustration of the complicity on the eastern front of German army officers with the Nazi genocide, a shameful fact that has only recently been acknowledged in Germany.

The most likely explanation for von Choltitz’s surrender in Paris is that he knew the hopelessness of his situation, wanted to save his own skin by avoiding a suicidal last stand, and thought that, by doing so, he could burnish his reputation once the war was over. Refusing to let Paris burn would be a most effective way to cover up his more sordid past. By making it seem as if only his brave decision saved the city from total destruction, von Choltitz entered the history books as a kind of hero instead of a war criminal.

There is, of course, nothing wrong with dramatizing history for the theater or the movies. In the larger story of the war, the actual motivations of Nordling and von Choltitz are of little importance. The only risk of historical fiction, especially in the movies, is that it ends up replacing in the public memory the facts of what actually happened. But Schlöndorff is not a historian. The best way to look at his film is as a love story about Paris. One can differ about the interpretation of events presented in the movie. It is hard to disagree about the worthiness of his love.

Volker Schlöndorff’s Diplomacy is playing at Film Forum in New York through Tuesday October 28.