Even as Ebola hysteria rages in the US, the epidemic here in Liberia, which is supposed to be its epicenter, seems to be subsiding. According to official counts, this impoverished West African country of 4 million people is currently home to fewer than four hundred Ebola patients. Not millions of patients; not tens of thousands of patients; not even thousands of patients. Fewer than four hundred patients. Even as the World Health Organization warns that any day now we could be seeing thousands of new cases, and Obama’s UN Ambassador Samantha Power claims the global response to the epidemic is “failing,” the number of new cases each week in Liberia is falling, not rising. In August, the streets of Monrovia were strewn with bodies and emergency Ebola clinics were turning away patients. Today, nearly half of the beds in those treatment units are empty. I’ve been here a week and have yet to see a single body in the street. Funeral directors say business is off by half.

Of course, the situation remains very serious. More than two thousand have succumbed to the disease here since the outbreak began—along with thousands more in neighboring Sierra Leone and Guinea, according to the CDC—and Liberia faces looming economic and political crises. This fragile country urgently needs help—both for the well being of its own people, and for the safety of the rest of this interconnected world. But the epidemic is far from the cataclysmic disaster currently on display on American TV screens. Why does this matter? By portraying Ebola as an out-of-control threat to humanity—the foolish calls for border controls, the needless and cruel quarantining of a healthy volunteer nurse, the canceling of contracts, trade and other exchanges—US politicians and the media are making the disease harder to fight. And that could make the epidemic far more dangerous than it currently is.

The Ebola virus first spread from southeastern Guinea to a rural area of Liberia in March. (Guinea shares its southern border with both Sierra Leone and Liberia.) By mid-April, Liberian Ministry of Health & Social Welfare officials and the medical charity Doctors Without Borders seemed to have contained the outbreak and there were almost no new cases in May. Then, in early June, the epidemic suddenly exploded in the slums of the Liberian capital Monrovia, and from there it spread to towns and villages around the country, reaching its peak in August.

Today, however, the situation is radically different. No one knows for sure what is responsible for the slow down in the disease’s spread, but it seems that many Liberians, who at first denied the epidemic was real, have come to their senses and changed their behavior by avoiding direct physical contact with sick or dead people. (Whether Sierra Leone and Guinea are seeing similar declines in new cases has not been reported.) At the same time, the government in coordination with international partners such as Doctors Without Borders has set up a system to isolate and care for patients and monitor their contacts for symptoms. Questions remain about why this epidemic was so severe in the first place, but it seems that this simple set of interventions, which has worked in the past to contain twenty-five previous known Ebola outbreaks in Africa since 1976, is belatedly working here too.

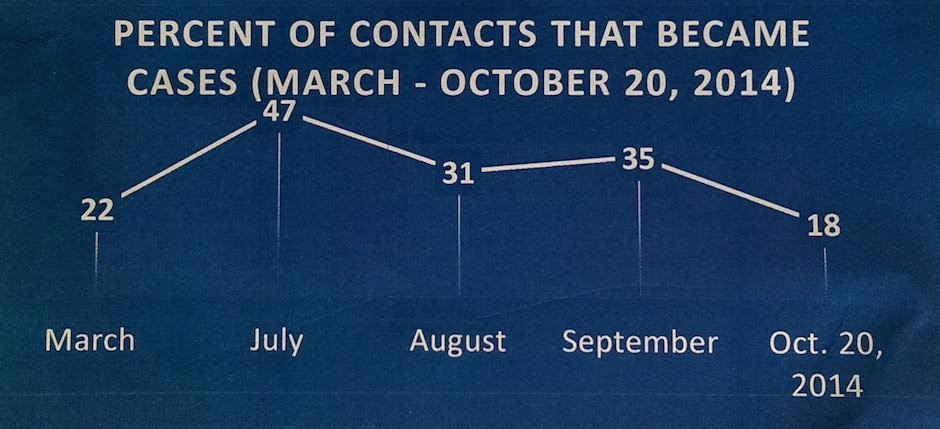

Is the decline in cases real? Aid groups warn that families could be hiding patients in slums and villages because they believe in voodoo and want to give their beloved a proper African funeral. No doubt there are such cases, but according to studies carried out here by scientists from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there appear to be few of them. CDC researchers working closely with Liberian officials have been scouring the country for sick people. In Monrovia, health workers travel from house to house in the slums checking on people who had contact with those who are already sick or have died. In July, nearly half of those contacts went on to succumb to the disease themselves. Today, fewer than 20 percent of them do.

Even in normal times, it’s hard to keep secrets in Liberian society. Neighbors tend to be friends, relatives or snoops; people live communally, wander in and out of each others’ houses and yards, feed each others’ children and share what few possessions they have. Most people live in tiny houses without locks on the doors, separated by narrow footpaths and passageways, and every community has a small number of leaders who know what everyone is up to. In Monrovia, everyone I’ve met is terrified of Ebola. A friend who runs Liberia’s national Ebola hotline says she frequently gets multiple reports for every case: sometimes as many as twenty people will call in to report a single patient.

Advertisement

The bad news is that in many other ways Liberia seems to be falling to pieces. Shops are shuttered, schools and hospitals are closed, the government has failed to pass a budget, crucial legislative elections have been postponed, flights have been cancelled and mines, factories, and oil wells have been abandoned in the panic. In Monrovia, life on the surface seems fairly normal. Market women sell their vegetables on the street, huge trucks lumber through the narrow streets, many shops are open and the hotels are full. But the customers are mainly aid workers on Ebola contracts and the people who supply them, and those aid workers won’t be here forever. Business people who keep an eye on the economy are quietly terrified. Liberia’s GDP—$2.7 billion in 2012—is smaller than that of many large US companies, but it was growing by a healthy 8.3 percent annually before the epidemic. In the worst case scenario, growth could fall to zero in 2015, according to the World Bank.

For any nation this would be troubling; in Liberia it threatens to undo years of effort to bring stability to the country. Between 1980 and 2003, Liberia was a basket case, presided over by a murderous tyrant backed by the Reagan administration and then by a series of warlords whose power relied on gangs of machine gun-wielding children and drug-addled rebels wearing wedding gowns and wigs. After the civil war finally ended the place was in ruins. Basic services like electricity, water, and health care were scarce and only 35 percent of Liberians could read. But thousands of exiles, many of them educated in Western countries and highly skilled, returned to help those left behind rebuild. Despite a series of depressing corruption scandals since then,life was improving, partly because the nation’s relentlessly critical press, business community, and civil society served as checks on government power.

Last week I met a former cabinet minister whose job was to attract investment to Liberia. He carries around a little notebook and when news of the epidemic first began appearing in American newspapers over the summer, he copied down some of the comments that people wrote in response to the articles: “Let Ebola run its course!”; “Are those people capable of evolving?”; “Africa: the land of intellectual barbarism”; “Why are we sending our troops to that cesspool?” and so on. I asked him why he felt the need to record such statements. “The only way the economy can grow is through internal investment and foreign investment,” he explained. “There isn’t much internal investment because people are poor, so as minister, I worked hard to restore investor confidence in this country because it’s really our only hope.” With misinformation feeding a blaze of paranoia across the United States about this “African” disease, that one hope is threatened.