In 1940 the Nazis released a propaganda film called The Eternal Jew. The film claimed to show the Jews in their “original state,” “before they put on the mask of civilized Europeans.” Stagings of Jewish rituals were interspersed with scenes of yarmulke- and caftan-wearing Jews shuffling down crowded alleys, all meant to show the benighted nature of Jewish life. Above all, the filmmakers focused on Jewish faces. They trained their cameras in lingering close-up on their subjects’ eyes, noses, beards, and mouths, confident that the sight of certain stereotypical features would arouse responses of loathing and contempt.

The designer of the film’s poster evidently agreed, avoiding more obvious symbols of Jewish identity (skull-cap, sidecurls, Star of David) in favor of a single dark, hook-nosed, fleshy face. Indeed, the poster hardly needed the accompanying title. In Europe in 1940, this representation of Jewishness was widespread: similar depictions of Jews could be seen on posters and in pamphlets, newspapers, even children’s books.

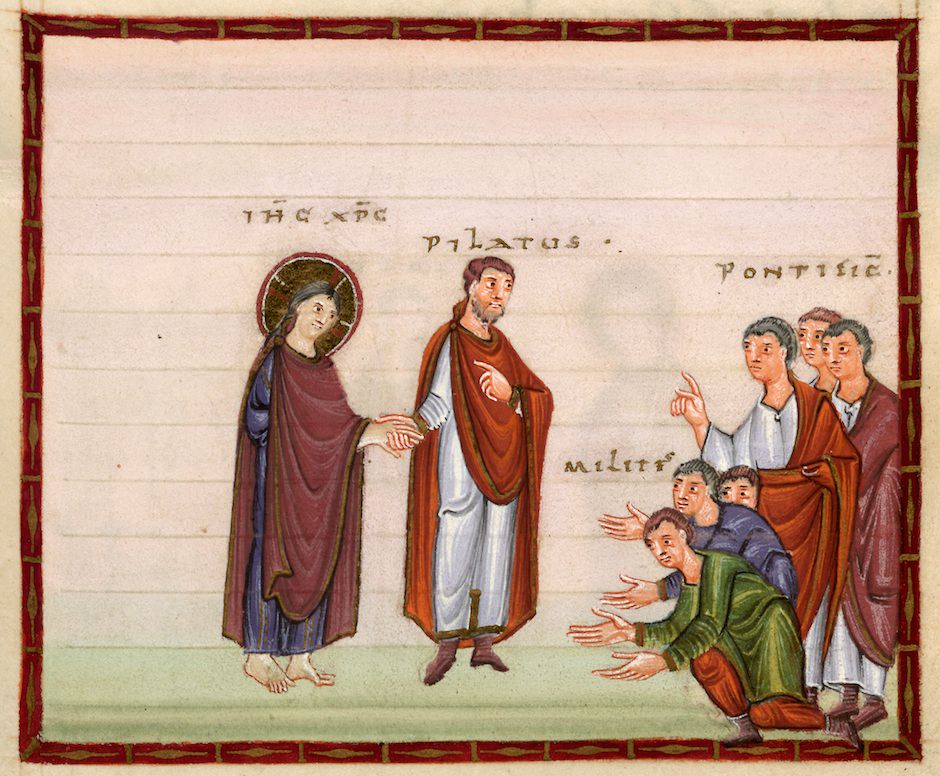

This image of the Jew, however, was far from “eternal.” Though anti-Semitism is notoriously “the longest hatred,” until 1000 CE, there were no easily distinguishable Jews of any kind in Western imagery, let alone the stereotypical swarthy, hook-nosed Jew. Earlier monuments and manuscripts did depict Hebrew prophets, Israelite armies, and Judaic kings, but they were identifiable only by context, in no way singled out as different from other sages, soldiers, or kings. Even nefarious Jewish characters, such as the priests (pontifices) who urged Pilate to crucify Christ in the Egbert Codex (circa 980), were visually unremarkable; they required labels to identify them as Jewish.

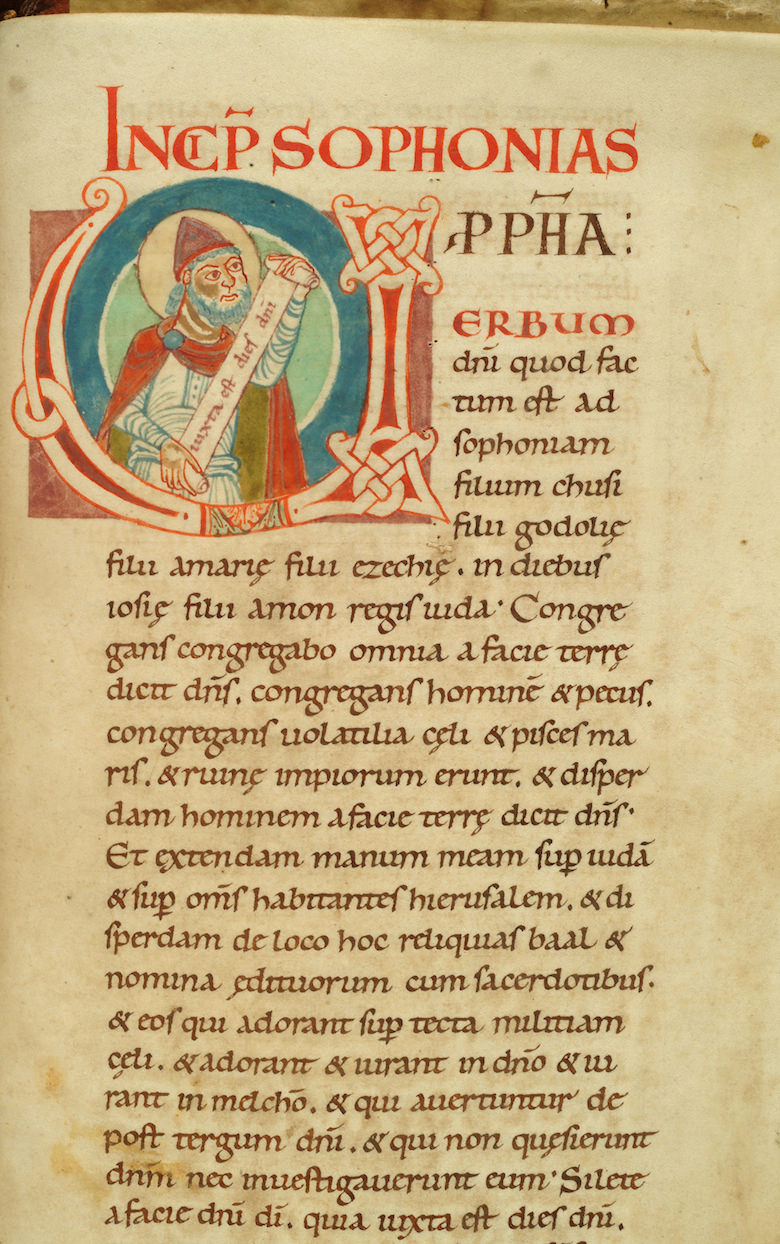

When Christian artists did begin to single out Jews, it was not through their bodies, features, or even ritual implements, but with hats. Around the year 1100, a time of intensified biblical scholarship and growing interest in the past, as well as great artistic innovation, artists began paying new attention to Old Testament imagery, which had been relatively neglected in favor of New Testament illustration in early medieval art. Hebrew prophets wearing distinctive-looking pointed caps began appearing in the pages of richly illuminated Bibles and on the carved facades of the Romanesque churches that were then rising across western Christendom.

The prophets’ headgear had nothing to do with actual Jewish clothing (there is no evidence that Jews at the time wore such hats, or any hats at all, for that matter—religious Jews did not regularly cover their heads until the sixteenth century). The “Jewish pointed cap” is based on the miters of ancient Persian priests and symbolized religious authority. The same hat had long appeared in manuscripts, frescoes, mosaics, and ivory carvings on the heads of the Three Magi, those “wise men of the East” who brought gifts to the infant Jesus, and so clearly had no negative connotation. Rather, the hat gave the innovative artworks in which Hebrews appeared an aura of sacred antiquity, and so helped defend the new image-drenched buildings and manuscripts from accusations of “novelty”—a dire charge in medieval Christendom, a conservative society that feared change. For the same reason, the prophets wear beards, symbols of maturity, wisdom, and dignity. (As with the hats, the beards have little to do with actual Jewish appearances or religious practices. Jewish men were by no means uniformly bearded at this time.)

But the appearance and meaning of Jews in Western art would change over time, as Christian concerns and devotional needs changed. Moreover, art affects as well as reflects ideas. Marking Hebrews in art influenced the way Christians imagined and thought about Jews; Christian attitudes and policies toward Jews consequently transformed as well. In one remarkable case of life imitating art, in 1267, two church councils ordered that Jews be required to wear pointed hats “as their ancestors used to do.” In the absence of centuries-old photo albums, one must conclude that the primary evidence for how Jews “used to” dress was Christian art.

After hat-wearing Hebrew prophets had appeared in Christian artworks for several decades, around 1140, the original Persian association was forgotten. Pointed hats became signs of Jewishness. They began to appear on a broad range of Judaic figures—not just Old Testament prophets and patriarchs, but also Jewish characters from literature and legend. In these new contexts, the previously positive qualities of antiquity and authority had less positive connotations. In an enamel triptych dated circa 1155 now in the Morgan Library, the Jew named Judas Cyriacus, whom the Roman Empress Helena forced to reveal the location of the True Cross, is no revered prophet. His hat and beard serve to confirm the antiquity, and so the reliability, of his information. But they also mark him as clinging to a sterile and superseded law. Here the hat serves as a representation of the Christian doctrine of supersession, which held that Hebrew rules and rites were rendered obsolete by more “spiritual” Christian practices.

Advertisement

In the second half of the twelfth century, a new devotional trend promoting compassionate contemplation of the mortal, suffering Christ caused artists to turn their attention to Jews’ faces. In an enamel casket dating to about 1170, the central Jew in the group to the left of the crucified Christ has a large, hooked nose, all out of proportion both to his own face and to the noses of the other figures on the casket. Though this grotesque profile resembles modern racialist anti-Semitic caricature, it does not seem—yet—to bear the same meaning. No Christian texts written up to this point attribute any particular physical characteristics to Jews, much less refer to the existence of a peculiar “Jewish nose.” Instead of signaling ethnic hatred, this Jew’s ugly visage reflects contemporary Christian concerns. In accord with the new devotions, artworks had just begun to portray Christ as humbled and dying. Some Christians struggled with the new imagery, discomfited by the sight of divine suffering. Proponents of the new devotions criticized such resistance. Failure to be properly moved by portrayals of Christ’s affliction was identified with “Jewish” hard-hearted ways of looking. In this and many other images, then, the Jew’s prominent nose serves primarily to draw attention to the angle of his head, turned ostentatiously away from the sight of Christ, and so links the Jew’s misbegotten flesh to his misdirected gaze.

For the rest of the century, and for several decades beyond, the shape of Jews’ noses in art remained too varied to constitute markers of identity. That is, Jews sported many different kinds of “bad” noses—some long and tapering, others snout-like—but the same noses appeared on many “bad” non-Jews as well, and there was no single, identifiable “Jewish” nose. By the later thirteenth century, however, a move toward realism in art and an increased interest in physiognomy spurred artists to devise visual signs of ethnicity. The range of features assigned to Jews consolidated into one fairly narrowly construed, simultaneously grotesque and naturalistic face, and the hook-nosed, pointy-bearded Jewish caricature was born.

This image served many purposes. In being so fleshily vivid and realistic, the Jew’s face seemed to embody for Christian viewers the physical, secular, material world, a realm with which Jews had long been associated in Christian polemic. This explains why an illustration designed to display the worldly sovereignty of the German Emperor Henry VII depicts him accepting a scroll offered by a physiognomically caricatured Jew.

In other cases, the caricature conveyed error and infidelity. In a fourteenth-century illustration of Psalm 52 (“The Fool says in his heart: ‘There is no God’”), no hat is needed to identify the wine-guzzling Fool as a Jew; it is clear from his features alone. The illumination does not exclusively indict Jewish unbelief, however. It was customary for the Psalm 52 Fool to be portrayed as a cudgel-wielding idiot, sinner, churl, or jester; we can therefore identify the other figure on the page as a second Fool. But in the company of our caricatured Jew, and in light of his very different (that is, perfectly generic) features, we are forced to read him as a specifically “Christian” (or at least Gentile) unbelieving Fool. In spite of its nasty anti-Jewish caricature, then, this image hardly acts to differentiate Jews from Christians. Indeed, it complicates the idea of the Jew as Christians’ moral “Other,” by emphasizing the flawed nature of both Jewish and Christian faith.

It is hard to take comfort in this ecumenical moralism, however. All too often, the power of the images—the vividly “real,” fleshy difference of the caricatured Jew’s face—overwhelmed their subtle spiritual message. Christian attitudes toward self, faith, and God changed less noticeably toward the end of the Middle Ages than did Christian attitudes toward Jews. Four centuries of seeing pointy-hatted, big-nosed, bearded Jews in art had conditioned Christians to regard Jews as different and socially distant. When they did not find such differences and distance in reality, they imposed them by law—in the notorious Jewish badge statutes, in laws forcing Jews into marginal neighborhoods and occupations, or, in the ultimate flexing of sovereign muscles, by expelling Jews from entire realms.

Advertisement

The “eternal Jew” and “the longest hatred” are equally misleading labels. Neither Jews themselves nor attitudes toward Jews were static or unchanging. Even apparently identical images can bear radically different meanings. But the history of anti-Jewish iconography does reveal one constant in Western culture, well known to Nazi propagandists—the visceral force of the visual image.

Sara Lipton’s most recent book, Dark Mirror: The Medieval Origins of Anti-Jewish Iconography was published this month by Metropolitan Books.