Renaissance philosophers, musing on European voyages to the New World, speculated that the dispersal of gold deposits throughout the globe was part of God’s plan to spur travel, exploration, and communication between continents. In antiquity, other metals had the same effect: tin and copper for smelting bronze, lead for leaching other metals out of ore and slag, and, most crucially in the late second and early first millennia BC, iron for making tools, armor and weapons. This “Iron Age,” as historians often term the seven or eight centuries preceding the start of the Greek classical period (circa 500 BC), saw trade and travel that not only linked the Mediterranean nations but moved goods between lands as far removed as modern Iran and western France. This is the focus of the vast and impressive exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, “Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age.” With objects grouped according to the cultures that produced them and also arranged loosely in a chronological sequence spanning nearly a millennium, this show presents a vast panorama of the Iron Age and an exploration of the commerce and connections between its major civilizations.

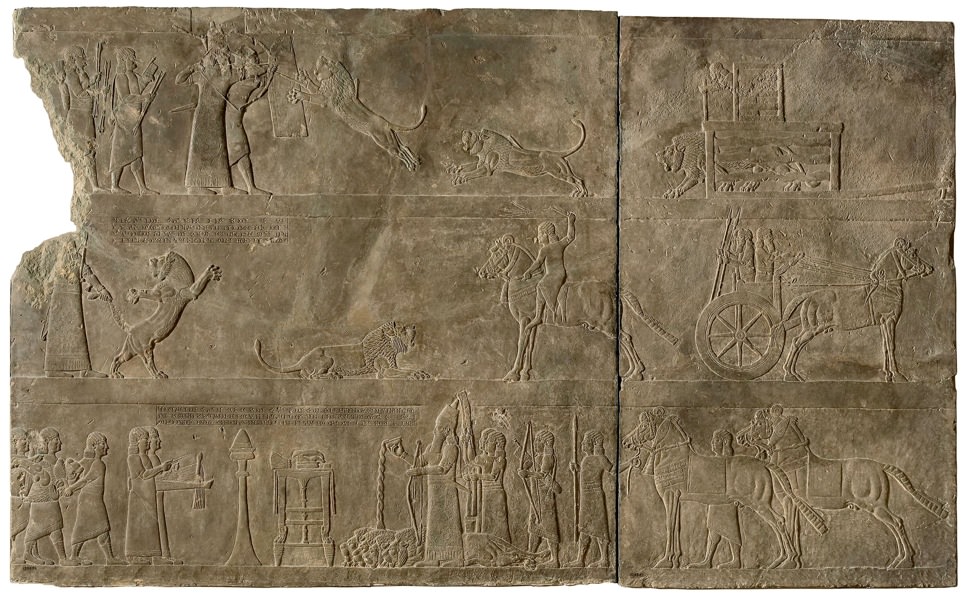

Political instability in the Near East was the driving force behind much of this interconnectedness. Around 1200 BC, the Hittite and Babylonian empires, the superpowers who dominated the Tigris and Euphrates valleys at the heart of the ancient Near East, collapsed, for reasons not well understood (the Mycenaean Greek cities of the Homeric epics were destroyed at about the same time). In the centuries that followed, an aggressive Assyrian state rose to prominence and then fell in its turn, ceding supremacy around 600 BC to the Babylonians (in what is now western Iraq), newly energized under the warrior-kings Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar. Meanwhile, around the periphery of the Mesopotamian region, numerous small kingdoms—Urartu, Phrygia, Aramaea, and a group collectively called the Syro-Hittite kingdoms—jostled against one another, and against the major powers, in a ceaseless rivalry for stature and territory. A huge and remarkably detailed stone relief in the Met exhibition, carved by Assyrian hands in the mid-seventh century BC, reveals the violence of one such struggle: Assyrian troops are seen routing soldiers of Elam at the battle of Til Tuba (in what is now southern Iran), and beheading their captives, including the Elamite king Teumann, recognizable in several scenes by his receding hairline.

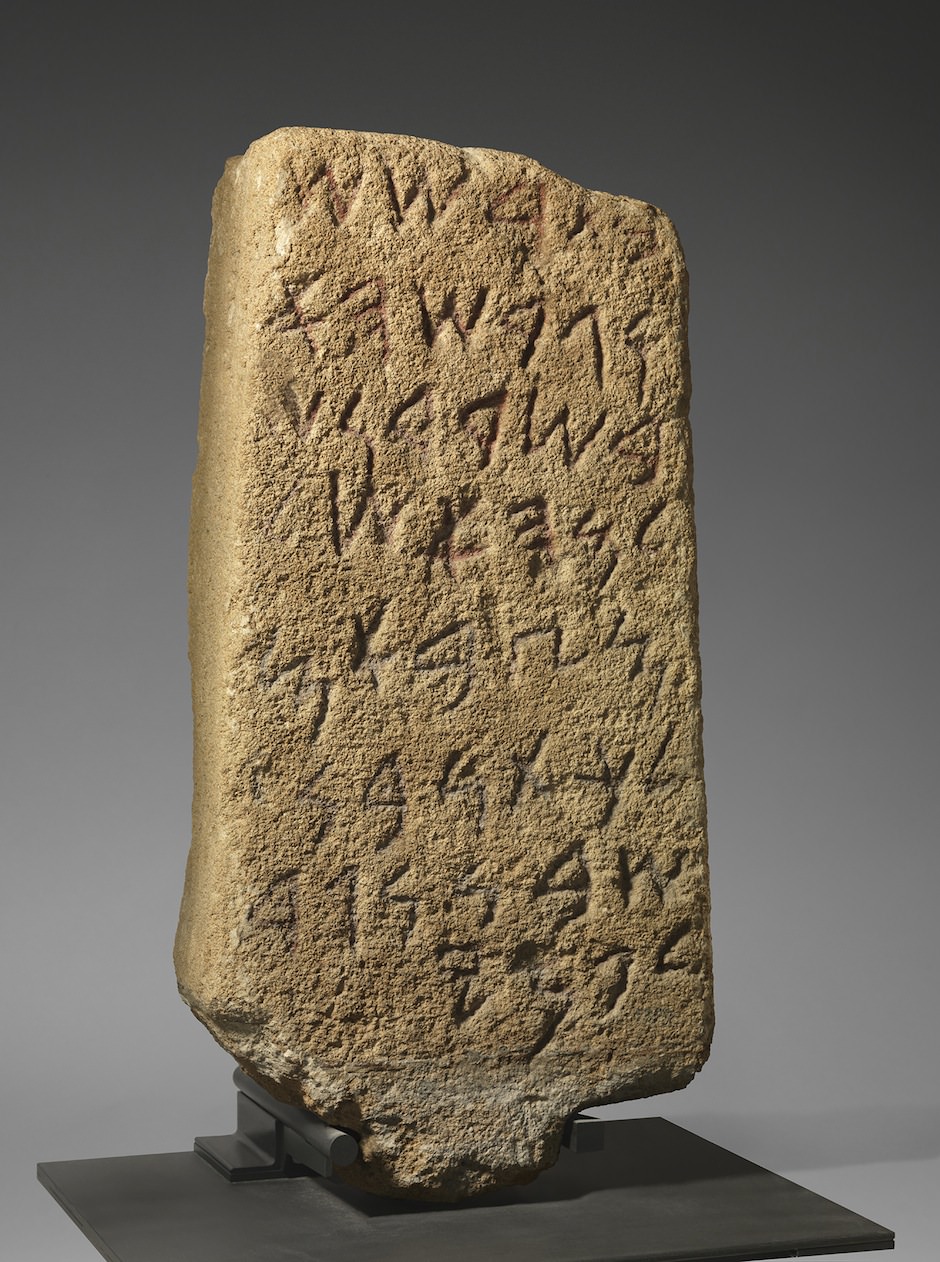

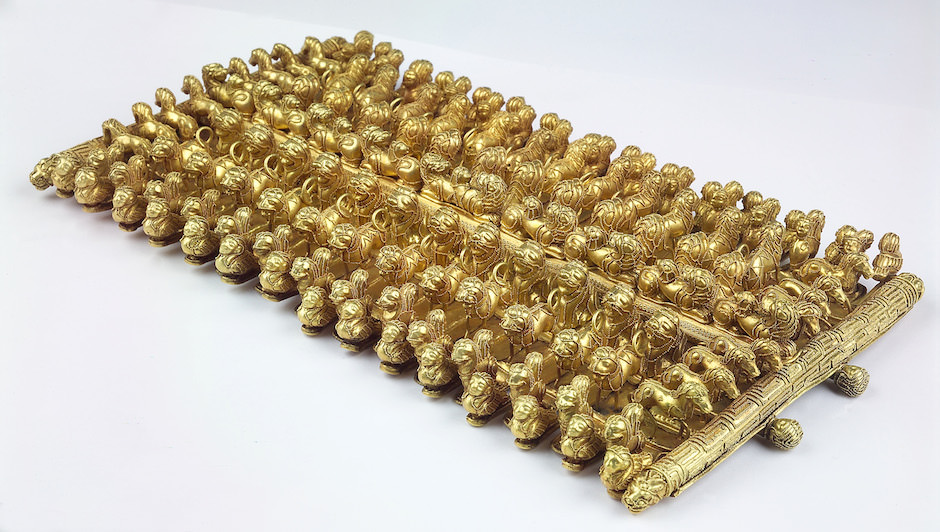

Weapons-grade iron was thus in high demand by western Asian states where deposits were scarce, Assyria in particular, and the Phoenicians, expert sailors based on the Levantine coast, were ideally positioned to meet this demand. Phoenician traders established trading posts all across the ancient world, including the North African coast, the islands of the Mediterranean, and both southern and western coasts of the Iberian peninsula. They left their mark on many cultures: their round-bottomed merchant vessels controlled the route to Tartessos, on the mineral-rich Atlantic coast of Spain. Homer’s Odyssey depicts the Phoenicians as dangerous and deceptive visitors who trouble the Aegean with raids and kidnappings. But the Greeks also thought their own city of Thebes had been founded by a Phoenician, Cadmus, a civilizing hero who brought “Cadmean letters,” or alphabetic writing, to the region. Phoenician artworks are well represented at the Met exhibition, including many carved out of ivory—delicate hair combs, narrative reliefs, and wonderfully expressive nude female figures, breasts cupped in their two hands, probably votive images representing the fertility goddess Astarte. But perhaps the most striking Phoenician object is an inscribed sandstone stele found at Nora on Sardinia. Dated to around 800 BC, it bears witness to the Phoenician export of “Cadmean letters” to Europe, where they gave rise to the Greek and Roman writing systems and thus to most of those used today.

Sardinia served as an important way-station for Iron Age navigators sailing to ore-laden shores further west. The coast of southeastern Spain was rich in lead, a substance vital to the silver-smelting process known as cupellation, and two different Phoenician shipwrecks from these waters are explored in this exhibition. One consists of two ships that went down off Mazarron in the seventh century BC. Nearly all of their cargo was comprised of plain lead ingots, but a ceramic amphora and dish, perhaps the ship captain’s mess kit, was also recovered from one of them. The second shipwreck site, at nearby Bajo de la Campana, yielded more diverse finds: ingots of lead, copper, and tin, elephant tusks inscribed with Phoenician characters, luxury goods of all kinds, and a two-foot-high limestone altar. A fascinating (though also distractingly noisy) video loop shows the process by which the Bajo de la Campana ship was excavated, only a few years ago.

Bronze, the alloy that had predominated in weapons and tools during the second millennium BC, continued in use during the first, but now served mainly for ceremonial or domestic objects, including statuettes, bowls, and mirrors (since bronze could be polished to make a highly reflective surface). Large bronze cauldrons were apparently treasured by the elite members of Aegean societies as marks of status, especially if elaborate adornments called protomes, often in the shape of griffin’s heads, extended from their shoulder or rims. The Met show includes splendid examples of these griffin-head protomes found on Rhodes and Samos, as well as a magnificent intact cauldron, adorned with both griffin and human heads, recovered from a tomb on Cyprus. Readers of Herodotus will be reminded that the first Greeks to voyage to Tartessos, beyond the Straits of Gibraltar, dedicated just such a griffin-head cauldron to the goddess Hera in her temple on Samos.

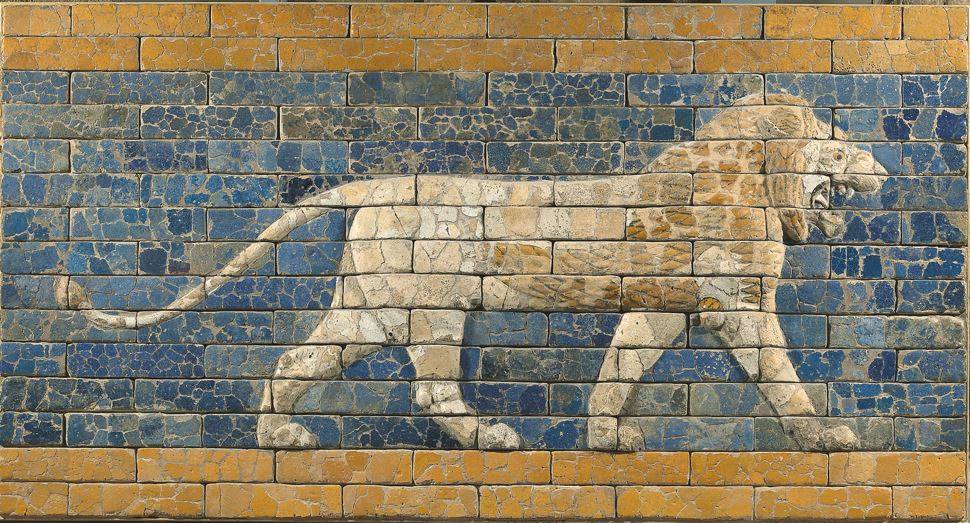

Indeed the pages of Herodotus’ Histories, or the historical books of the Hebrew Bible, often seem to come to life in this extraordinary show, as a visitor encounters, in room after room, the rulers and conquerors described in those texts: Croesus of Lydia, Midas of Phrygia, David of Judaea (referenced in an Aramaic inscription of the ninth century BC, the sole historical evidence for a monarch otherwise known only through the Bible), Sargon and Sennacherib of Assyria, Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon. The rises and falls of these monarchs are illustrated here in their narrative reliefs, portrait stelae, and inscribed pillars—the monuments they erected to vaunt their victories over enemies and rivals, constructing their own legends for their subjects and, perhaps, for posterity—and in the Met’s highly evocative visualizations of their palaces and temples. In the show’s final room, devoted to the resurgent Babylon of the seventh century BC, one beholds a stunning modern model of the Ishtar Gate and Processional Way, as glazed-brick reliefs of fabulous beasts, once embedded in those structures, gaze down from overhead; nearby, another model recreates the ziggurat called Etemenanki, Nebuchadnezzar’s temple to the god Marduk, thought by some to have inspired the tale of the tower of Babel. The aspirations of Iron Age kings were great indeed, and the Met’s “Assyria to Iberia” has been conceived on a correspondingly grand and inspiring scale.

“Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 4.