What does satire do? What should we expect of it? Recent events in Paris inevitably prompt these questions. In particular, is the kind of satire that Charlie Hebdo has made its trademark—explicit, sometimes obscene images of religious figures (God the father, Son, and Holy Spirit sodomizing each other; Muhammad with a yellow star in his ass)—essentially different from mainstream satire? Is it crucial to Western culture that we be free to produce such images? Do they actually work as satire?

Neither straight journalism nor disengaged art, satire alludes to recognizable contemporary circumstances in a skewed and comic way so as to draw attention to their absurdity. There is mockery but with a noble motive: the desire to bring shame on some person or party behaving wrongly or ignorantly. Its raison d’ȇtre over the long term is to bring about change through ridicule; or if change is too grand an aspiration, we might say that it seeks to give us a fresh perspective on the absurdities and evils we live among, such that we are eager for change.

Since satire has this practical and pragmatic purpose, the criteria for assessing it are fairly simple: if it doesn’t point toward positive change, or encourage people to think in a more enlightened way, it has failed. That doesn’t mean it’s not amusing and well-observed, or even, for some, hilarious, in the way, say, witty mockery of a political enemy can be hilarious and gratifying and can intensify our sense of being morally superior. But as satire it has failed. The worst case is when satire reinforces the state of mind it purports to undercut, polarizes prejudices, and provokes the very behavior it condemns. This appears to be what happened with Charlie Hebdo’s images of Muhammad.

Why so? Crucial to satire is the appeal to supposed “common sense” and a shared moral code. The satirist presents a situation in such a way that it appears grotesque and the reader who, whatever his or her private interests, shares the same cultural background and moral education agrees that it is so. The classic example, perhaps, is Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal of 1729. Swift’s target was Protestant England’s economic policy in Catholic Ireland and the disastrous poverty this had created. After paragraphs of statistics on population and nutrition, we arrive at the grotesque:

I have been assured … that a young healthy child well nursed, is, at a year old, a most delicious nourishing and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricasie, or a ragoust.

By selling their children for food, the pamphlet claims, the poor can save themselves an expense and guarantee themselves an income. Disoriented, every reader is made aware of a simple principle we all share: you don’t eat children, even Irish children, even Catholic children. So, if those children are not to be left to starve, something else in Ireland will have to give.

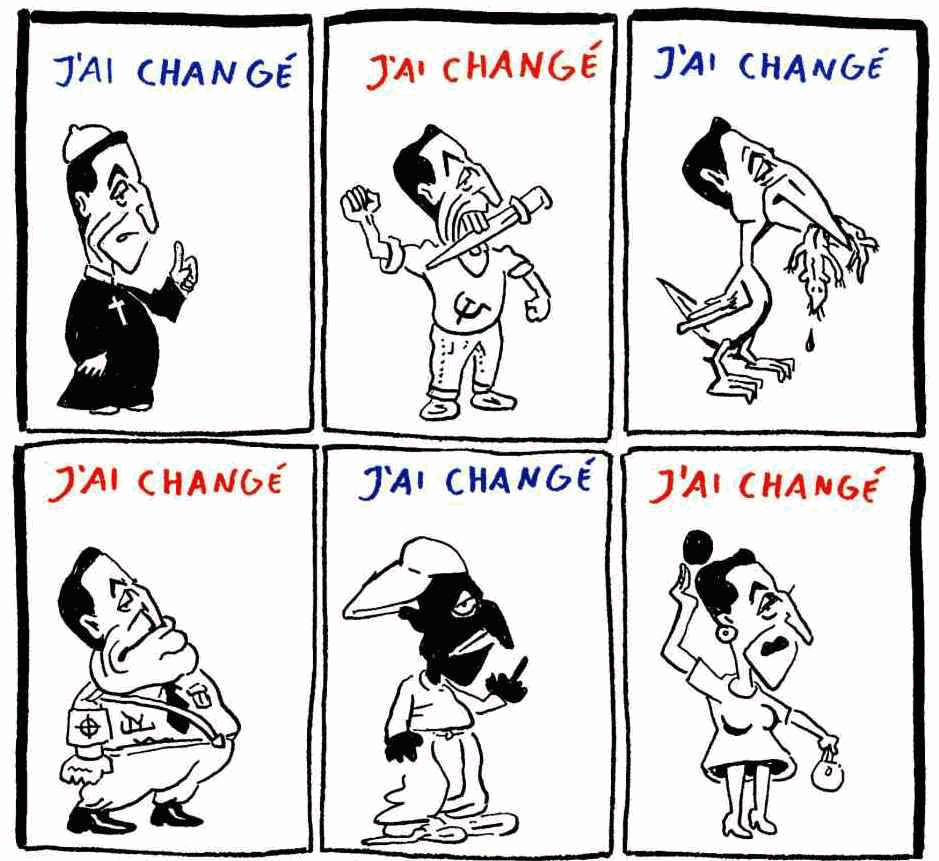

This appeal to what we all know and share becomes more difficult when satire addresses itself to people from different cultures with different traditions. In this regard, the history of Charlie Hebdo is worth noting. It grew out of a left-wing magazine, Hara Kiri, later Hebdo Hara Kiri (where Hebdo is simply short for hebdomadaire—weekly), which was formed in 1960 to address national political issues and subsequently banned on a number of occasions. When it was banned in 1970 over a mocking headline about Charles de Gaulle’s death its editors reopened it under a different name to avoid the ban, calling it Charlie Hebdo to distinguish it from a monthly magazine, Charlie, that some of the same cartoonists were already running. Charlie was Charlie Brown, but also now, comically, Charles de Gaulle. Its focus was on French politics and when it was felt to have overstepped the mark the democratically elected French government was in a position to impose a temporary closure. It was a French affair.

Wound down for lack of funds in 1981, Charlie Hebdo was resurrected in 1991 when cartoonists wanted to create a platform for political satire about the first Gulf War. With this explicitly international agenda the relationship between satirists, readers, and targets became more complex. The readers were the same left-wing French public, used to seeing fierce attacks on all things sacred, but the targets sometimes lay outside France or at least outside mainstream French culture. In 2002 the magazine hosted an article supporting controversial Italian author Oriana Fallaci and her claims that Islam in general, not just the extremists, was on the march against the West. In 2006, Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons of Muhammad and reprint of the Danish cartoonist Jyllands-Posten’s controversial Muhammad cartoons led to the paper’s selling 400,000 copies, rather than the normal 60,000 to 100,000. Popularity and notoriety had arrived through mockery of a target outside French culture but with which an aggrieved minority in France now identified.

Advertisement

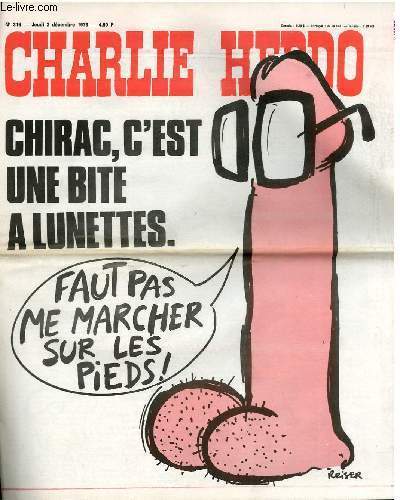

Sued by the Grand Mosque, the Muslim World League, and the Union of French Islamic Organizations, the paper’s editors defended themselves, insisting that their humor was aimed at violent extremists, not at Islam itself. Islamic organizations didn’t see it that way. While President Chirac criticized satire that inflamed divisions between cultures, various politicians, Hollande and Sarkozy included, wrote to the court to defend the cartoonists, Sarkozy in particular referring to the ancient French tradition of satire. Eventually the court acquitted the paper and freedom of speech was upheld. But the effect of the cartoons had been to inflame moderate areas of Islam. The ancient French tradition of satire was creating more heat than light. It was also uniting French politicians usually opposed to each other against a perceived threat from without.

It is said, by contrast, that Christian leaders have now grown used to their religion being desecrated and pilloried in every way. This is not entirely the case. In 2011 Charlie Hebdo noted that while Muslims had sued the paper only once, the Catholic Church had launched thirteen cases against it. In the 1990s, writing satirical pieces for the Italian magazine Comix, I had my own experience of the difficulties of attacking the church through satire. In this case too an issue of cultural blindness was involved. Reacting to yet another Vatican condemnation of abortion, even in cases of rape, I suggested that if the Catholic Church really cared about abortion it might perhaps change its position on contraception and actually manufacture condoms with images of the saints, or perhaps even prickly hair-shirt condoms, or San Sebastian condoms, so that lovemaking would be simultaneously an indulgence and a penitence, and people would be mindful of their Lord even between the sheets. Comix refused to publish.

This was not, I believe, a question of self-censorship or lack of courage on the magazine’s part. The editors of Comix were perfectly ready to attack the Church on issues of abortion and birth control. They just didn’t think that the idea of people having sex with condoms showing their favorite saint was the right way to go about it. Too many of their readers—mostly Catholic by culture if not practice—would be offended; it would not help them to get distance and perspective on the debate. Knowing Italy and Italians better now, I reckon they were right. It was my Protestant background and complete carelessness about images of saints and virgins that made me unaware of the kind of response the piece would have stirred up.

Most likely, however, that same Italian public would have had no problem with the drawings of Muhammad that provoked the massacre at Charlie Hebdo last week; because they, like me, but unlike the vast majority of Muslims, set no value on the image Muhammad. When I see Charlie Hebdo’s cartoon entitled “Muhammad overcome by fundamentalists,” showing a weeping Muhammad saying, “It’s tough being loved by assholes,” I smile and take the point. For a Muslim reader perhaps the point is lost in the offense of a belittling representation of a figure they hold sacred.

Where we’re coming from and who we’re writing to is important. Not all readers are the same. In The Satanic Verses (1988), Salman Rushdie includes a dream sequence where the prostitutes have the names of Muhammad’s wives. There are also various provocative reinterpretations of Islam, but certainly nothing that would disturb a Western reader, and in fact the novel was on the shortlist for Britain’s Booker Prize for fiction without even a smell of scandal in the air. Only as publication was approaching in India and the paper India Today ran an interview with Rushdie did the controversy begin in earnest, with riots, deaths, and eventually the Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa calling for Muslims to kill Rushdie.

It is, in short, this mixing of cultures and immediate globalization of so many publications through the Internet that makes satire more problematic as the Swiftian appeal to the values we share becomes more elusive. In the Inferno Dante could imagine Muhammad in hell, his body obscenely split open—“from the chin right down to where men fart”—as fit punishment for his crime of religious schism. The Divine Comedy was not intended for publication in India. Needless to say any such representation of Christ would have been unthinkable.

The following questions arise: Now that the whole world is my neighbor, my immediate Internet neighbor, do I make any concessions at all, or do I uphold the ancient tradition of satire at all costs? And again, is a culture that takes mortal offense when an image it holds sacred is mocked a second-rate culture that needs to be dragged kicking and screaming into the twenty-first century, my twenty-first-century that is? Do I have the moral authority to decide this?

In his response to the attack on Charlie Hebdo in Paris, the cartoonist Joe Sacco makes the distinction between the right to free expression and the sensible use of it. One might be free, he says, to draw—as he does to illustrate—a black man falling out of a tree with a banana in his hand, or a Jew counting money over the entrails of the working class, but of what possible use are these images? And actually of course we’re not free. In Italy and Germany it is illegal to display certain images that recall Fascism and Nazism. Denial of the Holocaust is a crime in France. In the United States and Britain, our freedom—in practice—to indulge in racist, anti-Semitic, misogynist, and homophobic insults has been notably limited, at least since the late 1980s when notions of “political correctness” became increasingly pervasive. Even Charlie Hebdo fired a cartoonist for anti-Semitism. None of these restrictions have proved a great loss, at least for me.

Joe Sacco’s take on the tragedy in Paris is smart. In raising the question of the usefulness or otherwise of a cartoon, rather than remaining fixated on the question of freedom of speech, he reminds us of the essentially pragmatic nature of satire. However grotesque and provocative its comedy, its aim is to produce an enlightened perspective on events, not to start riots. At this point, and notwithstanding a profound sense of horror for the evil and stupidity of the terrorist attack on the magazine’s offices, one has to wonder about Charlie Hebdo’s pride in constantly dubbing themselves a “Journal Irresponsable.” The current edition of the paper shows Muhammad in such a way that his white turban looks like two balls and his long pink face a penis. The Prophet is being dubbed a prick. He holds a Je suis Charlie placard and announces that all is forgiven. The print run was extended to five million copies after a first run of three million sold out; this up from a standard run of 60,000. Is it likely this approach will help to isolate violent extremists from mainstream Muslim sentiment?