“Countless freeloaders, lost teenagers, parents of lost teenagers, and disappointed artists have found consolation in Vincent van Gogh’s misfortune,” writes Michael Kimmelman in The Review’s February 5, 2015 issue. “His story is the ultimate ‘I told you so’: a troubled, not obviously talented oddball, who through determination and sheer chutzpah is finally, albeit mostly posthumously, recognized as a genius.” We present below a series of van Gogh’s sketches and paintings, with commentary drawn from Kimmelman’s piece.

—The Editors

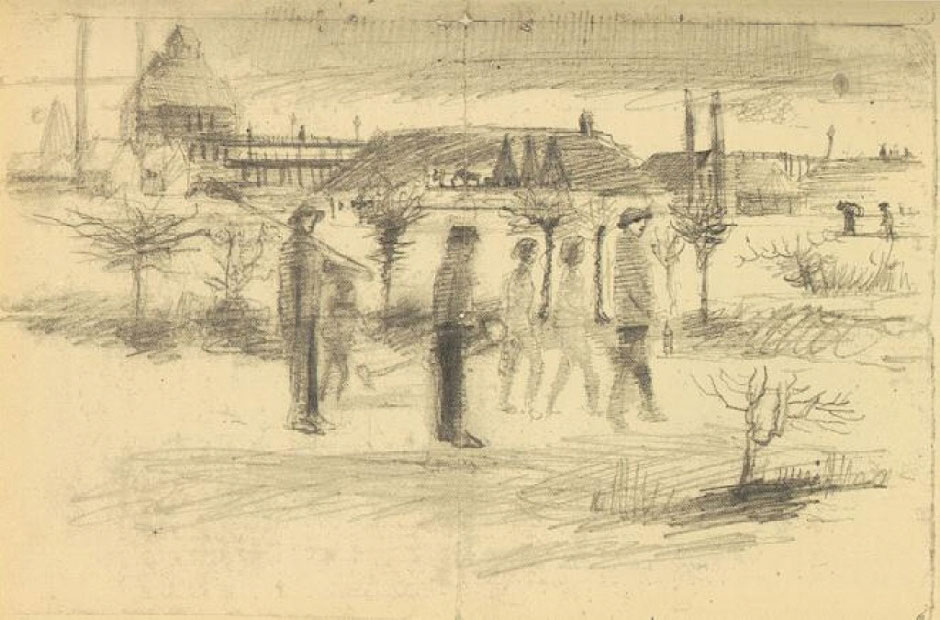

Vincent’s early subjects—laborers and vagrants, prostitutes, orphans, peasants and housemaids, hard at work—were drawn with compassion but without skill at conveying their particularity and weight. They were symbols, types. A drawing like Miners in the Snow is a typically uncertain field of scratches and stick figures. Even so, the seeds of something special were being sown.

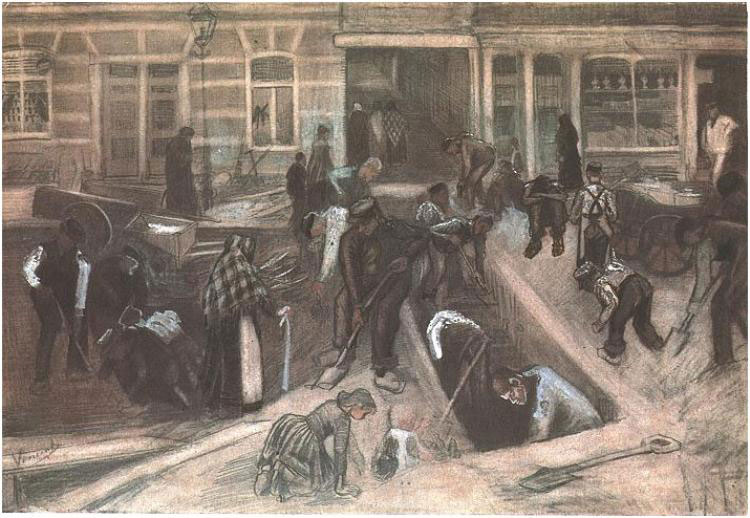

George Hendrick Breitner, a painter of street scenes and gritty, Zola-like naturalism, took van Gogh to soup kitchens and construction sites, from which came drawings like Torn-Up Street with Diggers, from April 1882, a collage of working-class characters, disposed willy-nilly with not much thought to perspective.

Van Gogh drew a number of scenes of solitary figures in winter fields and other landscapes, like this one of a tortured stand of pollard birches—the trees like “a procession of almshouse men,” as Vincent described them. Its spiky aura leaps off the page. You can see in these drawings a distinct vocabulary of cursive script: electrified, blanketing patterns of lines, akin to metal filings pulled by some invisible force across sheets of paper.

The Potato Eaters, with its sacramental, earthen scrum of peasants, like a grove of gnarled tree trunks around a pine table, was the work that Vincent would value above all others to the end.

By 1887, van Gogh abandoned heavy impasto and reveled in an expressive range of dots and dashes, lattice lines, and basket-weave patterns. His years of etching helped: printmaking had taught him how to suggest movement through the directions of stippled lines. It all comes together by the autumn of 1887 in canvases like Quinces, Lemons, Pears and Grapes.

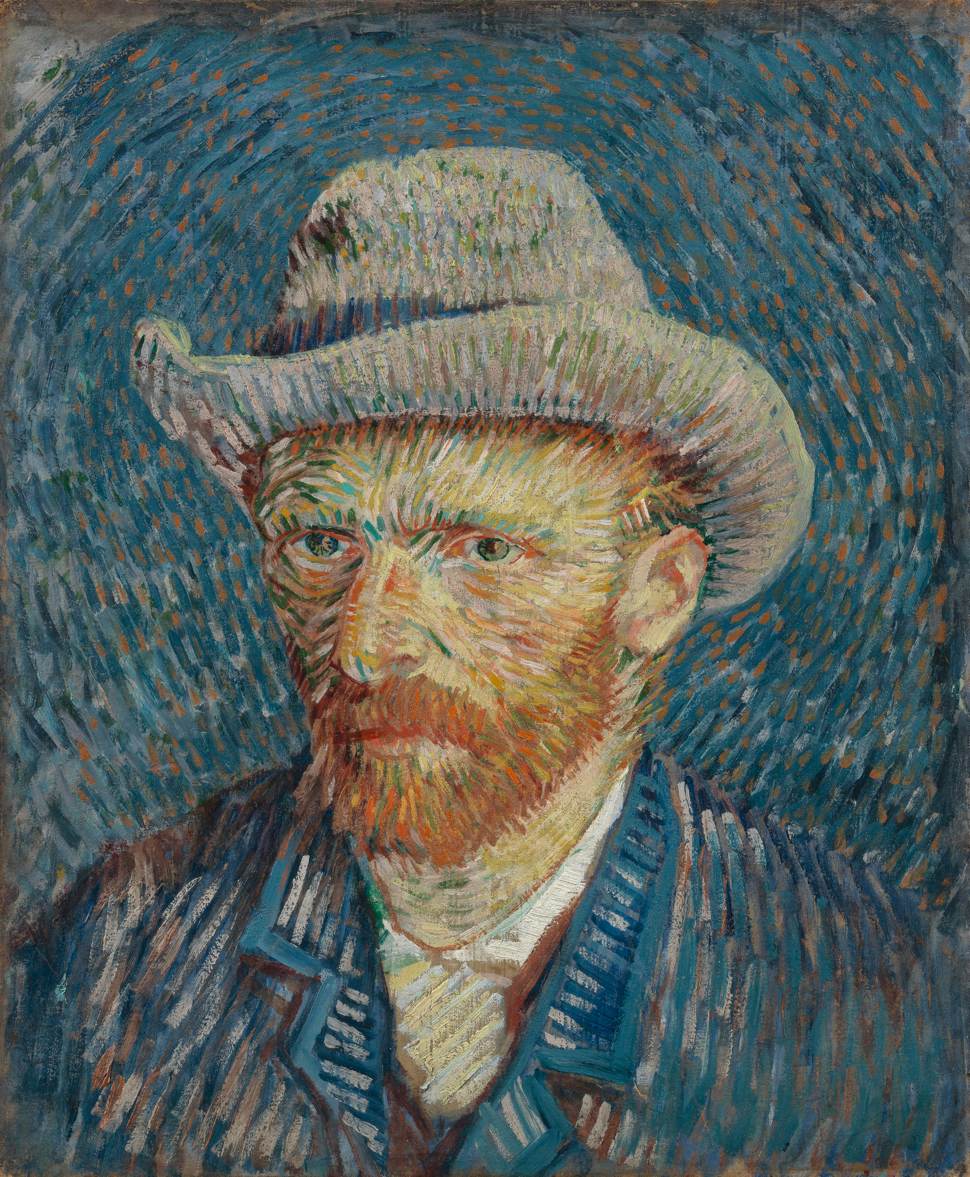

His late portraits beat with the blood of real people; they’re not ham-fisted symbols but animated, sympathetic, alive. Those roiling, curlicue clouds in The Starry Night become vibrating, all-over patterns of lines in a self-portrait where the artist’s face is engulfed by a force field of raw energy.

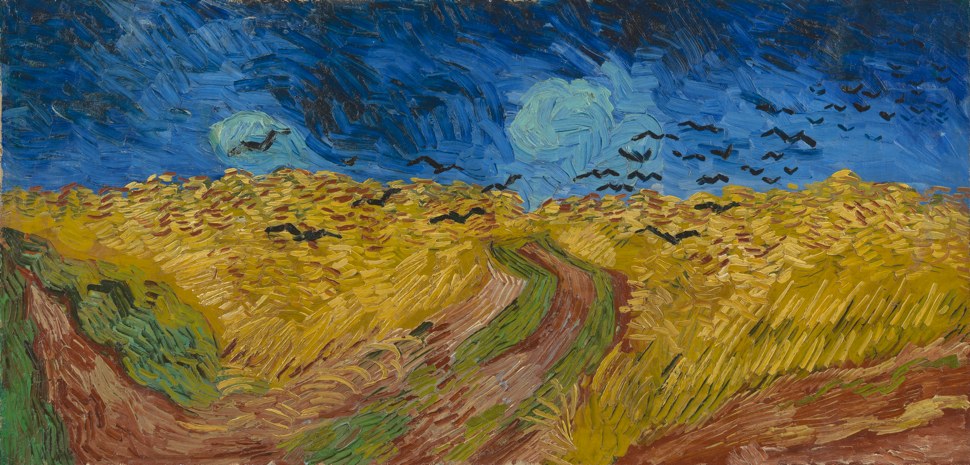

Late in his life, van Gogh finds solace painting wheat fields, in what Julian Bell calls the “most frantically fluent canvases of his life.”