In Paul Bowles’s preface to A Life Full of Holes (1964), the extraordinary dictated memoir of an illiterate Moroccan named Larbi Layachi, Bowles describes the incident that helped Layachi understand the nature of storytelling:

Charhadi [the pseudonym under which Layachi first published his memoir] used to call by to see me from time to time, usually in the evening on his way home from the cinema. On one of these occasions he had been to see an Egyptian “historical” film. People in this part of the world are prone to confuse the intent of feature films with that of newsreels. When I told him how fictional films are made and what they are meant to be, he was particularly struck by the fact that it is not forbidden to “lie.” I said that no one thought of film-making in those terms.

But now, it seems, they do. The recent controversies about the accuracy of “historical” films including Selma, The Imitation Game, and The Theory of Everything have made me think of the easy certainty with which Bowles assured his friend that no one expected a feature film to adhere to the standards expected of a newsreel. Until recently, I’d assumed it was understood that Hollywood would emphasize the “story” aspects of history, and that a distortion of real events, on screen, would hardly constitute a lie. Except for those cases in which I felt that a film was being used as propaganda—Zero Dark Thirty comes to mind—I’d never been particularly disturbed, and certainly not surprised, to learn that a feature film had altered a real event so as to ramp up the drama. At what point, I wonder, did we start expecting films to tell the truth about the past? And won’t we be in trouble if we do?

Perhaps my skepticism about holding such films to rigorous standards of veracity has something to do with the fact that I grew up during an era in which “historical” films routinely departed so far—and often so comically—from reality. Among my favorites was Ivanhoe (1952), in which Robert Taylor starred as Walter Scott’s knight opposite Elizabeth Taylor as the exotic Jewess, Rebecca. Another was The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men (1952), with Richard Todd as the bandit of Sherwood Forest and Peter Finch as the Sheriff of Nottingham. From these films, I learned that there had been wars fought in distant lands and that they were known as “the Crusades”; that there had been a king named Richard the Lionheart who had been detained in “the Orient” and that his brother, the evil King John, had attempted to usurp his throne; that monks like jolly Friar Tuck wore robes and tonsures; that bows and arrows were the military weapons of choice; and that knights spent all their time competing in equestrian tournaments and rescuing damsels in distress. Later, of course, I would learn what had been falsified, ignored, or omitted from the interstices between the cinematic banquets and jousts: the slaughters perpetrated by the Crusaders, the costly local wars, the fear of plague, the sufferings inflicted by the feudal system.

Lately I’ve watched a few of the films I’d loved when I was young, to see how fast and loose they played with the facts. Among the more fanciful, but still oddly engrossing, is The Life of Emile Zola (1937), directed by William Dieterle and starring Paul Muni as its titular hero. The morose, socially phobic Cézanne is portrayed as a goofy bon vivant, given to sketching prostitutes in crowded cafes. The fact that Alfred Dreyfus was a Jew is mentioned only in passing, and nowhere is it suggested that anti-Semitism had anything to do with his case. Zola’s death from carbon monoxide poisoning, the result of a blocked chimney, is presented as purely accidental, though it has often been suggested that he was murdered in reprisal for his defense of Dreyfus.

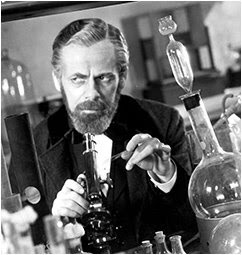

A year before their Zola film, Dieterle and Muni made The Story of Louis Pasteur, which gets quite a bit of the science wrong, and, less explicably, invents a daughter for Pasteur. One can hardly imagine the Curies’ courtship resembling the Hollywood-cute romance between Greer Garson and Walter Pidgeon in Madame Curie (1943), and—at least according to the film’s IMDB page—Marie’s explanation in the film of the theory of radioactivity lands fairly wide of the mark.

But when I was very young, all that went over my head. What got my attention was the fact that men named Zola and Dreyfus existed, and that a woman had won the Nobel Prize in science: a concept that came as a something of shock to a little girl growing up during the height (or the depths) of the Mad Men 1950s. I recall being enthralled by the achievements of Pasteur (he saved a little boy from rabies!) and the Dreyfus case. And my fascination with Ivanhoe and Robin Hood persisted. I wrote my college senior thesis on a thirteenth-century romance, and until I dropped out of graduate school, I had planned to become a medievalist.

Advertisement

With my own early experiences of historical films in mind, I took my eight-year-old granddaughter to see Selma. In many ways it was a mistake; the film was more brutal than I expected, and each thunk of a club or a boot against the flesh of the demonstrators and their supporters rumbled and shook the theater. That the film was rated PG-13 suggested that the ratings board imagines the average thirteen-year-old as a seasoned, even hardened, veteran of film violence.

My granddaughter hid her eyes during the film’s many bloody parts, as did I; and the discussions about strategies, tactics, and governmental opposition were mostly lost on her. But by the time we left the theater, she understood how brave the demonstrators had been and why the Civil Rights struggle had been necessary: not an easy concept for a second-grader at an ethnically and racially diverse Brooklyn public school. And though the violence made the film painful to sit through, to underplay what the activists—and ordinary people—had endured would have been much worse than misrepresenting the part played by Lyndon Johnson. Later, I thought, my granddaughter and I can deal with the film’s historical mistakes.

As a member of a generation that, because of Johnson’s stand on Vietnam, underestimated or ignored his admirable record on domestic issues, I was sorry to see him cast as the villain of a story in which his actual involvement was much less obstructive. Mythicized versions of history, however apparently harmless and mild, can leave a permanent mark. A friend said she found it difficult to read T.E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, which she greatly enjoyed, without conjuring up the image of Peter O’Toole in Lawrence of Arabia.

Were I a director, I would want to avoid the sort of errors and exaggerations that make reasonably knowledgeable audiences so dubious and uneasy about what they’re being shown that it ruins their pleasure in watching. Presumably this is what happened to the writers who have helpfully pointed out what Selma and the other films got wrong. Inaccuracies, one hopes, are less likely to lodge in our minds if we are made aware of what they are.

Meanwhile I can’t help noticing the difference between historical films whose veracity stirs up a controversy and historical films about which nobody seems to care if they’re true or not. One need only compare the tenor of the conversations generated by the mistakes in Selma and (to a somewhat lesser extent) The Imitation Game with those kicked up by the question of what Mike Leigh did and didn’t get right in his brilliant Mr. Turner; in fact, it would seem, not many people went to see Leigh’s biopic about the landscape painter, J.M.W. Turner, though it was one of the best films of last year.

But why should that be surprising? Which subject is our society more anxious about? Race, segregation, homosexuality—or nineteenth-century British art? The chatter about most biopics—Big Eyes and Get On Up, among others—is, by contrast to the arguments over Selma, so soft as to be almost inaudible.

So perhaps the real source of controversy isn’t the question of truth in historical films, but rather the subjects of historical films—and how vexed those subjects are. As Pierre Curie, Walter Pidgeon was already playing the scientist as eccentric and socially inept. But what made that cliché more problematic in The Imitation Game was the cinematic treatment of Alan Turing’s homosexuality. Hyde Park on Hudson (2012) was apparently rife with unproven supposition, but the sex life of FDR failed to stir up anything near the passions aroused by the films about Turing or Martin Luther King. In fact, the historical debate surrounding Selma has been directly linked to current debates about race relations, with some interpreting the Academy’s snub of the film as a reflection of Hollywood resistance to a black director and a film about a different kind of black hero. Some have argued that Ava DuVernay’s failure to be nominated as Best Director was a result of Selma’s historical inaccuracies, while others have maintained—rather more convincingly—that it reflects Hollywood’s resistance to honoring a black woman director. And David Oyelowo, who played Martin Luther King, suggested that he wasn’t nominated as Best Actor because the culture prefers black actors to play subservient roles.

Advertisement

Movies that deal with race and homosexuality allow us to talk about (or around) these touchy and delicate topics, by giving special scrutiny to the films’ fidelity to history. It’s so much easier and less threatening to talk about whether (or how much of) a film is “true” than to confront the unpleasant—and indisputable—truth: that racial and sexual prejudice have persisted so long past the historical eras in which these films are set.

Part of a continuing New York Review series on films nominated for the 2015 Academy Awards.