One night in the 1980s, a low period for me, as I slumped on my regular stool at Farrell’s, in Brooklyn, staring into my fourth or fifth of their enormous beers, the gentleman to my left struck up a conversation. Like nearly everyone in the bar but me, he was a cop, a retired cop to be exact, and unlike most of them he looked like a churchwarden, lean and grave and puckered, definitely on the farther shore of eighty. He had much to say; his proudest accomplishments had gone unrecognized. It seemed he had been the first to put together a numbered list of the most-sought reprobates from justice. He’d gotten the idea sometime in the late 1940s, he recalled. He had been listening to Symphony Sid, his favorite radio disk jockey. It was the week that “Twisted” by Wardell Gray moved into the pole position on the chart. The idea of a Top Ten was itself new.

There were some good cases on tap that week, too. Someone had stolen all the sacramental vessels, worth many thousands, from the sacristy at St. Patrick’s; someone else had apparently scaled the sheer face of a skyscraper to murder a diplomat in his heavily-guarded thirty-fifth-story bedroom; a gang of miscreants in fright masks had walked off with the gate receipts during the seventh inning of a game at the Polo Grounds. My friend deplored these crimes, naturally, but still felt they deserved something more than the usual tabloid-headline form of appreciation. He imagined a Top Ten of crimes—the Most Audacious Felonies. He saw himself announcing the list on the radio, becoming a personality, a sensation. There would be a spin-off comic book with his name and face at upper left, “presenting” the felonies to an eager public. In the meantime he got himself some sheets of oaktag and posted a list in the squad room.

His superiors were not amused. He was informed that as a property clerk his job was to keep track of evidence and exhibits and not go inserting his nose in places where it did not belong, and he was furthermore forcibly reminded why at age forty-five he was still nothing more than a property clerk—my new friend did not enlighten me on that particular score. Not a week later, however, a list appeared on every bulletin board of every precinct house in the city. Nicely typed and roneographed, it was headed “The Ten Most Wanted Men.” Immediately my friend knew just which ambitious, sniveling lieutenant it was who had stolen his idea, but there was nothing he could do about it. Adding insult to injury, the FBI caught wind of the list and called the plagiarist down to D. C. to advise on the creation of a nationwide Top Ten. By the end of the month the rat was heading up his own Special Squad.

Right away the list entered popular culture. It was just as my friend imagined it, down to the comic book, although J. Edgar Hoover was the personality charged with “presenting” it. The FBI list—the Ten Most Wanted Fugitives—garnered the lion’s share of publicity, but the New York City version, which evolved into the Thirteen Most Wanted, more than held its own. My friend, who was not short of contacts on the other side of the law, had any number of stories about crooks vying for a position, gunning for the number-one man in order to take his place, becoming depressed and allowing themselves to be arrested when they were bumped down to number fourteen, and so on. The public, for their part, were intoxicated—the number of wanton misidentifications and groundless accusations of bosses and neighbors and rivals in love more than quintupled, and so correspondingly did the number of false arrests. Even more than during the “public enemy” craze of the 1930s, law enforcement had become a spectacle.

At some point in the late 1950s, my friend made the acquaintance of a boy, a “bohunk” from Pittsburgh, who had come to town to become an artist. He didn’t say how they met, but they seem to have become rather close, although he didn’t think much of the boy’s attempts at art. The boy liked to draw “fruity” things, like women’s shoes, and serenely ignored my friend’s attempts to steer him toward something more substantial, such as true-crime comics. Still, they had some good times before the boy started becoming a success, designing greeting cards and wallpaper and shopping bags, and began thinking himself “too good” for my friend. As the boy became ever busier attending fancy cocktail parties on Fifth Avenue, their acquaintance languished. My friend was sad, but moved on, and had put the boy well out of his mind by 1962 or so, when like the rest of America he was made aware of a huckster who was making a fortune painting pictures of soup cans. He laughed when he read the story in the Daily News, but the laughter caught in his throat when he saw the picture next to it. It was the boy.

Advertisement

My friend had drifted through a couple of decades as a property clerk and, despite his early dreams of derring-do, had come to rather enjoy it. The job was steady, undemanding, and allowed him plenty of time to do the Jumble. He was a department fixture, almost synonymous with his job. That same year, though, his longtime nemesis, the plagiarist, became chief. And it could only have been his decision, made out of pure malice, to kick my friend down to patrol duty—my friend was nearing retirement, had been a model employee, had fallen arches. Anyway, it so happened that my friend was on the street in uniform on an unseasonably cold autumn evening, guarding a movie premiere, of all stupid things, when he saw the boy again. The boy now looked like an apprentice hoodlum: leather jacket, sunglasses, need of haircut. He was walking with that old movie star—what was her name? The boy spotted my friend, said nothing, but the two locked eyes for a second. Even through the sunglasses, my friend could tell.

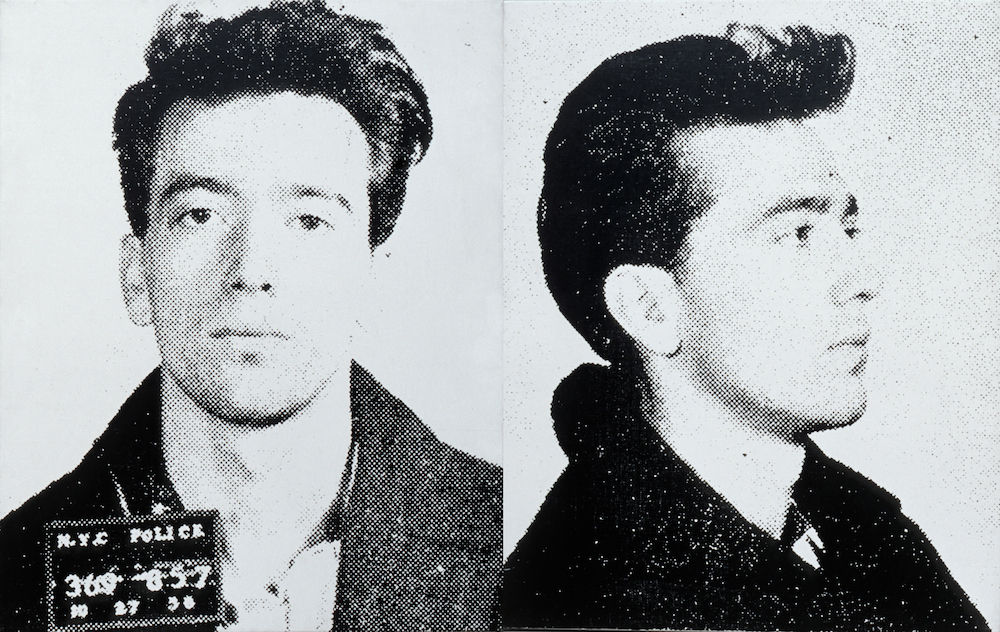

Cut to Spring, 1964. My friend, inches from retirement, had been patrolling the World’s Fair. One day he was called to the New York State pavilion. There might be trouble, he was told. As he approached he kept looking up at the piston-shaped towers, imagining a jumper. Only when he got close did he notice the lower building. It was covered with a row of enormous portraits of men. To his astonishment, he recognized them: the Thirteen Most Wanted. He stared at the faces in disbelief. But the instant he recognized the face of Salvatore Vitale, workers began obliterating it with white paint. One by one the faces disappeared. It was his dream—both realized and short-circuited—all over again. Somehow he found out, eventually: it was the boy! He did that! But was it an act of love, or an attempt to kill him?

This short story first appeared in Pinakothek, Luc Sante’s visual art blog, which he maintained anonymously from 2007 to 2009. The blog’s archives are now available on his site, lucsante.com. The images in this post are drawn from 13 Most Wanted Men: Andy Warhol and the 1964 World’s Fair: Conversations, published this month by the Queens Museum and the Andy Warhol Museum.

Images appear courtesy of the The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image captions, in order of appearance: Andy Warhol: Most Wanted Men No. 11, John Joseph H., Jr., silkscreen on canvas, 1964, photo by Axel Schneider; Andy Warhol: Most Wanted Men No. 2, John Victor G., silkscreen ink on linen, 1964; Andy Warhol: Most Wanted Men No. 7, Salvatore V., silkscreen on linen, 1964.