It has now become clear that Barack Obama is under enormous pressure to intensify the campaign against ISIS. Last week, as the White House held a summit on countering extremist violence in which Obama declared, “we are at war with people who have perverted Islam,” sources at the Pentagon told reporters that the retaking of Mosul, possibly with significant US military support, had been planned for as early as April. This followed the president’s recent announcement that he is seeking formal authorization from Congress for an all-out assault on ISIS in western Iraq and eastern Syria and that “our coalition is on the offensive” and the group “is going to lose.”

But the challenge of defeating the Islamic State is a huge one. The group is formidably armed, having captured large quantities and varieties of weaponry from Syrian and Iraqi forces. Its senior commanders include former officers of Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime in Iraq, a battle-hardened Chechen Islamist and former Georgian army sergeant, and veterans of the conflict in Libya. Above all, it has been able to attract unprecedented numbers of young recruits from the West itself—not least by drawing on apocalyptic currents in Islamic culture and thought in which the region of Greater Syria, known as Bilad al-Sham, is given paramount importance.

According to Europol, some five-thousand European nationals—mainly from the wealthier countries of northern Europe—have now joined the group, with around one thousand each from Britain and France. Among them are hundreds of young men and women still in their teens. Meanwhile, the caliphate’s tentacles now stretch from Afghanistan, to Yemen and to Libya, with Sunni affiliates and tribal groups making their allegiance (baya) to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the self-styled caliph of ISIS. As Sarah Birke has recently written in The New York Review, US officials are wondering why “ISIS has attracted so many fighters—the most rapid mobilization of foreign fighters so far, outstripping recruitment in the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan and the war against Saddam Hussein in Iraq.”

It is easy to see how ISIS, with its brutal executions and message of violent retribution against those who do not share its values, might appeal to individuals such as Amedy Coulibaly and the Kouachi brothers, the young men who perpetrated the killings in Paris in early January. (The Kouachis were also influenced by al-Qaeda in Yemen.) They were petty criminals and archetypal “losers,” living a marginal existence in a country whose Muslim immigrants have high levels of joblessness, low education attainment, and often difficulty finding social acceptance.

But many European jihadists do not seem to fit this template. On Thursday, it was revealed that “Jihadi John,” the London-accented ISIS executioner, is a university graduate trained in computer programming from a relatively comfortable London suburb. The casual brutalism of his online videos—he decapitated five Western and two Japanese hostages as well as numerous Syrian soldiers, and posed with the severed heads—suggests the insidious way that a generation brought up in cyberspace may have lost the connection between the real and its representation. Others who go to Syria have no Muslim background at all. In August 2013, it was estimated that 250 French citizens had joined jihadist groups there, and as many as forty of them (between 15 and 20 percent) were thought to be converts to Islam, a highly disproportionate number given that only 1 percent of Muslims in France are converts.

Recent reports in the international press have highlighted the extent to which ISIS has depicted Syria as the central battlefield in the final struggle between Islam and its enemies. Less known to Anglophone readers, however, is how these apocalyptic ideas have been especially effective in luring to Syria European teenagers who may have little prior exposure to mainstream Islam. Nor is this ideology exclusive to ISIS; Jabhat al-Nusra, the al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria and sometime rival of ISIS, has also used messianic rhetoric to attract large numbers of recruits from Europe. In France, those most likely to be vulnerable to such indoctrination are between sixteen and twenty-one years old—children on the threshold of adulthood.

As Dounia Bouzar shows in Ils cherchent le paradis ils ont trouvé l’enfer (They looked for Paradise and found Hell), her poignant account of French “orphan parents” who lose their children to the jihadist cause, French middle-class teenagers and medical students from atheist families are far from being immune to seduction by these jihadists groups. Bouzar’s story focuses on Adèle, the fifteen-year-old daughter of a professional couple in Paris who joins Jabhat al-Nusra after an online conversion by her handler “Brother Mustafa.” In a farewell note to her mother she leaves behind, Adèle writes:

My own darling Mamaman (Mamaman à moi)

…Its because I love you that that I have gone.

When you read these lines I’ll be far away.

I will be in the Promised Land, the Sham, in safe hands.

Because its there that I have to die to go to Paradise.

… I have been chosen and I have been guided.

And I know what you do not know: we’re all going to die,

punished by the wrath of God.

It’s the end of the world, Mamaman.

There is too much misery, too much injustice…

And everyone will end up in hell.

Except for those who have fought with the last Imam in the Sham,

Except for us.

Adèle’s family does not know exactly how she first became drawn to Islam. But as with so many other young recruits from Europe, the Internet seems to have played a crucial part. On Adèle’s computer, they discover pictures of her in a black niqab, as well as a record of her online conversion and rapid indoctrination by Brother Mustapha, in a hidden Facebook account in which she calls herself Oum Hawwa (“Mother of Eve”).

Advertisement

Her conversion appears to have been influenced by the sudden death of Cathy, her much-loved aunt, from an aneurysm at the age of forty. In the Facebook dialogue, Mustapha consoles her about her loss and asks: “Have you reflected on what I explained?”

“Yes, thanks be to God, my spirit is clearer. God called aunt Cathy back to bring me closer to Him. He did this so I would see the Signs that the ignorant don’t hear.”

“This is how He tests us,” says Mustapha. “ Everything is written—there is always an underlying meaning. Allah wanted you to learn. But He must send you a trigger so you can leave the ignorance in which you have been kept up till now. Your reasoning is merely human. Allah reasons as Master of the Universe.…”

As Adèle’s engagement strengthens, Mustapha becomes more strident, moving into grooming mode:

When I tell you to call me you must call me. I want you pious and submissive to Allah and to me. I can’t wait to see your two little eyes beneath the niqab.

The story ends tragically: in Syria, the girl is briefly married to Omar, a jihadi chosen by the Emir of her group. Then one day Adèle’s parents receive a text from Adèle’s cellphone: “Oum Hawwa died today. She was not chosen by God. She didn’t die a martyr: just a stray bullet. May you hope she doesn’t go to hell.”

In the hope of retrieving her daughter, Adèle’s mother, Sophie, receives help from Samy, a practicing French Muslim. He has just come back from Syria after failing to rescue his own fourteen-year-old younger brother, Hocine, who also joined al-Nusra. Samy explains the all-embracing ideology that drives the jihadists. After being kidnapped in Northern Syria, Samy had been brought before a leader of the French division of al-Nusra. “There were young French boys everywhere. An entire town of French recruits,” Samy recalls. He is told that the Syrian jihad and the restoration of the caliphate is a prelude to the final battle at the End of Time. He is warned not to listen to the Salafists (orthodox believers) who claim that waging jihad is subject to certain limitations. “God has chosen us! We have the Truth! You’re either with us or you’re a traitor,” he is told, in a phrase that echoes George W. Bush. “Only those who fight with the Mahdi”—the Muslim messiah, who will restore the caliphate—“will enter paradise.”

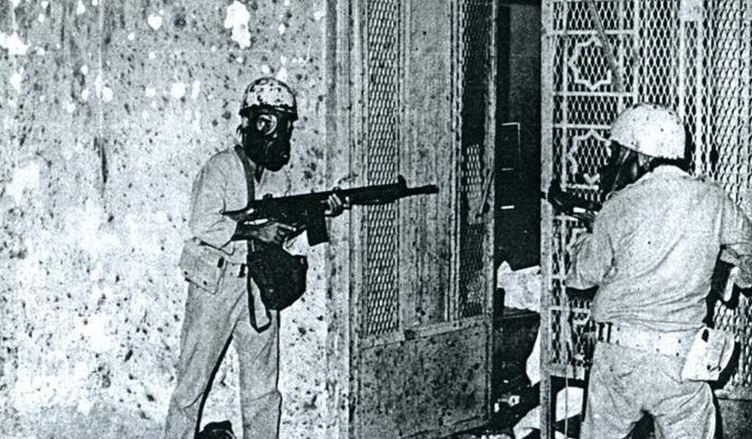

Though these ideas are not given prominence in most contemporary practice, the leaders of the Syrian jihad are not the first Islamic movement to give them special weight. In 1881, for example, the Sudanese Muslim cleric Muhammad Ahmad declared himself the Mahdi, conquered Khartoum, and created a state that lasted until 1898. And in 1979, an apocalyptic movement led by Islamist extremists brought Saudi Arabia briefly into crisis when it seized the Grand Mosque in Mecca and called for the overthrow of the House of Saud; the group claimed one of its own leaders as the Mahdi.

In fact, there is a strong pedigree for this ideology in classical Islamic thought. Like Christianity, Islam seems to have begun as a messianic movement warning that the Day of Judgment was imminent. The early suras (chapters) of the Koran are filled with doomsday menace, and the yearning for a final reckoning is deeply encoded in some of the texts. A central figure in this tradition is Dajjal—the one-eyed false messiah who corresponds to the Antichrist of the New Testament. The details vary but most versions agree that the final battle will take place east of Damascus, when Jesus will return as messiah, kill the pigs, destroy Dajjal, and break the cross in his symbolic embrace of Islam.

Advertisement

According to Jane Idleman Smith and Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad in The Islamic Understanding of Death and Resurrection (2002), no predictions about precisely when the End will come are provided in either Christian or Muslim scriptures: as the Koran puts it, “People ask you about the Hour. Say: ‘Knowledge of it rest with God.’” However, there are nearly fifty references to “the Hour” or the “Appointed Time” in the Koran and the signs by which it can be recognized are manifold and abundant:

Piety will give way to pride and truth to lies, while licentious practices such as music, drinking of wine, usury, adultery, homosexuality, and the obedience of men to their wives will prevail. Sex will be performed in public places, cousin marriage will give way to extrafamilial unions, and there will be no Imam to lead the faithful in prayer…

For jihadists, such signs are rife in the Middle East today. One of the arguments ISIS and al-Nusra put forward in their apocalyptic rhetoric is that the Bashar al-Assad regime—dominated by the minority and Shia-affiliated Alawite sect, with its killings of children and repression of Islamists—is a “sign” of this departure from fundamental Islamic values that is supposed to precede the final battle. A hadith in the collection of Ibn Kathir, an influential scholar who lived in Syria and died in 1373, describes other “signs” that instantly call to mind the contemporary Sunni-Shia divide and the burgeoning towers now dominating the skylines of Doha, Dubai, and other Arabian cities, including Mecca itself:

The Hour will not come till the following events have come to pass: people will compete with one another in constructing high buildings; two big groups will fight one another, there will be many casualties—they will both be following the same religious teaching; earthquakes will increase; time will pass quickly; afflictions and killing will increase…

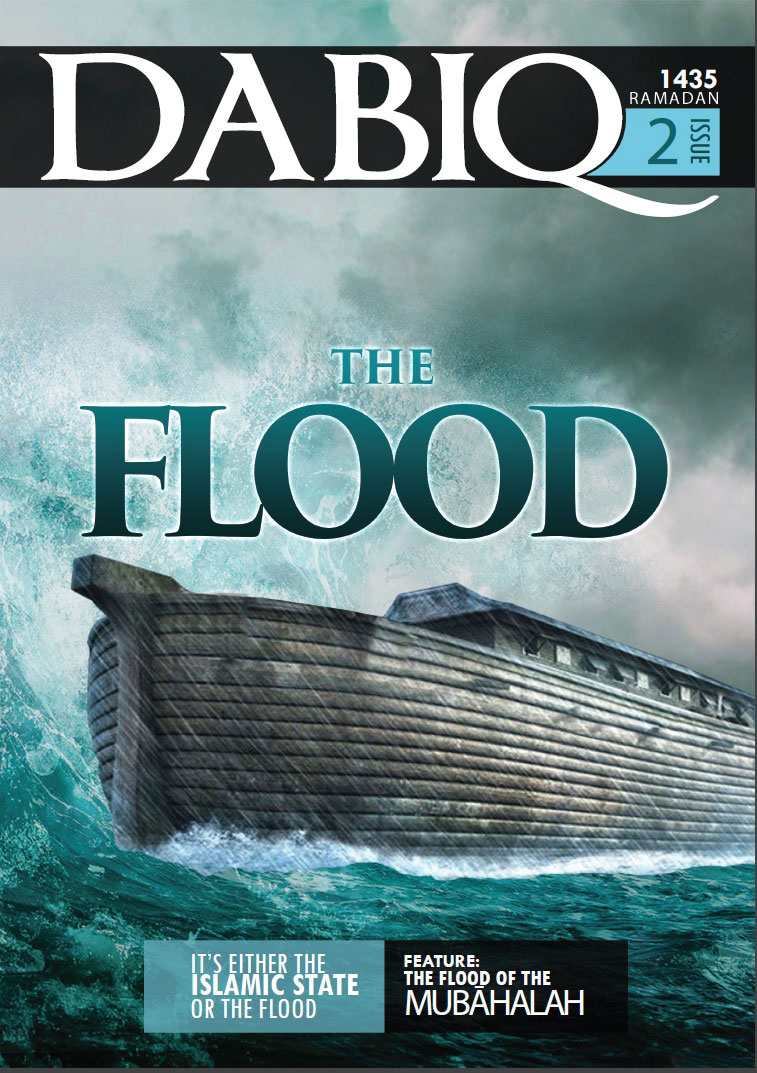

ISIS has also named its online magazine Dabiq, a reference to the small town near the Syrian border with Turkey that numerous hadiths (“reported sayings”) of the Prophet associate with the Islamic Armageddon, when righteous Muslims will come from Medina, defeat the “Romans” (a term classically applied to the Byzantine empire) and overrun Istanbul.

The parallels between this ideology and the beliefs adopted by Christian fundamentalists known as “premillennial dispensationalists,” who expect all born-again Christians to be “raptured” or physically transported to heaven while others perish in earthly mayhem, are so strong that it is hard to escape the conclusion that they draw on the same ancient reservoir of Near Eastern myth. In the Muslim version a great wind will take the souls of the believers, before the trumpet sounds and all are resurrected to face divine judgment.

There is a strand in messianic Islam, however, that does not feature in its Christian counterpart: the restoration of the caliphate, or what is supposed to be the true Islamic state under Sharia law and governed by a caliph, a Muslim sovereign who claims authority over all Muslims. There are several hadiths predicting that a true caliphate will follow unjust kingdoms as part of the End Times scenario. And the belief in the divinely sanctioned appearance of a true caliph has a deep association with the final battle against evil. Actual historic caliphates, such as the Sunni Abbasids (750-1258) and Ismaili Fatimids (909-1171), were propelled to power by messianic movements; though the final battle did not happen, al-Mahdi—the messiah—was used as a caliphal title.

Except at the very beginnings of Islam, and for a brief period in the High Middle Ages, the caliphate was not much of a functioning institution. But it did provide a powerful model of Islamic governance that, as Wael Hallaq, a leading authority on Islamic law who teaches at Columbia, argues, rested on “moral, legal, political, social and metaphysical foundations that are dramatically different from those sustaining the modern state.” Historically, Hallaq explains, the Sharia’s moral imperatives were effected outside the domain of the state:

The political absolutism that Europe experienced, the merciless serfdom of feudalism, the abuses of the church, the inhuman realities of the Industrial Revolution, and all that which made revolutions necessary in Europe were not the lot of Muslims, who, comparatively speaking, lived for over a millennium in a far more egalitarian and merciful system and, most importantly for us, under a rule of law that modernity cannot fairly blemish with critical detraction.

In the nineteenth century, the Ottoman sultans exploited this idea, reviving the caliphate with a view to countering the protective rights the Russian tsars and Austrian Habsburgs claimed over Christians living under Ottoman rule. If the tsar had rights over Christians living in the Near East and Balkans, the Sultan-caliph could claim the same rights over the tsar’s numerous Muslim subjects. World War I and the Russian and Turkish revolutions ended any such reciprocal idea, and Kemal Ataturk and the Turkish National Assembly’s decision to abolish the caliphate in 1924 met little if any resistance (though the “caliphal idea” was kept alive in India, where the Khilafat Movement supported by Gandhi, became a rallying point for both pan-Islamic unity and Hindu unity against the British Raj). Meanwhile, the division of former Ottoman lands among European nation states brought to an end a transnational Muslim empire more than five centuries old—an event that ISIS has explicitly condemned, in its much-publicized destruction of the Iraq-Syria border last year.

Hallaq’s analysis suggests that, for all the sadistic horrors that ISIS’s leaders exhibit in their campaign of “shock and awe,” they also aspire to a moral order that transcends not just the boundaries of the national state, but the moral logic underpinning it. Anchored in apocalyptic ideas that give it special meaning and purpose, this kind of transnational Islam seems to hold special appeal to young Europeans caught between competing identities, such as French-born people of North African descent who do not speak Arabic yet fail to gain acceptance as full citizens of France. The same considerations may well apply to three teenage Muslim girls from London’s Bethnal Green Academy School who recently flew to Turkey and have now been confirmed as having crossed into Syria to join ISIS. In Bouzar’s book, Samy explains that for such recruits, knowledge of Arabic is not necessary; the recruits are grouped by language and origins—the French-speakers, the English-speakers, the Chechens, the Moroccans—and united under the banner of jihad.

As Norman Cohn put it in his path-breaking study The Pursuit of the Millennium (1957), apocalyptic movements under a charismatic leader have always appealed to people who suffer from social alienation or who are seeking some new source of meaning:

On the strength of inspirations or revelations for which he claimed divine origins this leader would decree for his followers a communal mission of vast dimensions and world-shaking importance. The conviction of having such a mission, of being divinely appointed to carry out a prodigious task, provided the disoriented and the frustrated with new bearings and new hope…In the eschatological phantasies which they had inherited from the distant past….these people found a social myth most perfectly adapted to their needs.

Until we properly recognize this tradition, and the way it has been repurposed over the Internet to connect powerfully with thousands of international youth, we will have difficulty fulfilling Obama’s goal of destroying ISIS, of eradicating what he calls a cancer.