Can a writer’s original inspiration survive success?

Imagine you are Karl Ove Knausgaard at this point in his career. You have launched into a madly detailed, multi-volume exposure of your family life. You began the project in relative obscurity. The book was a major departure from the novels you had been writing before. The possibility that what you were writing would become a major national, then international literary “event” barely crossed your mind. There was simply the turmoil and excitement and hard work of putting new territory on paper.

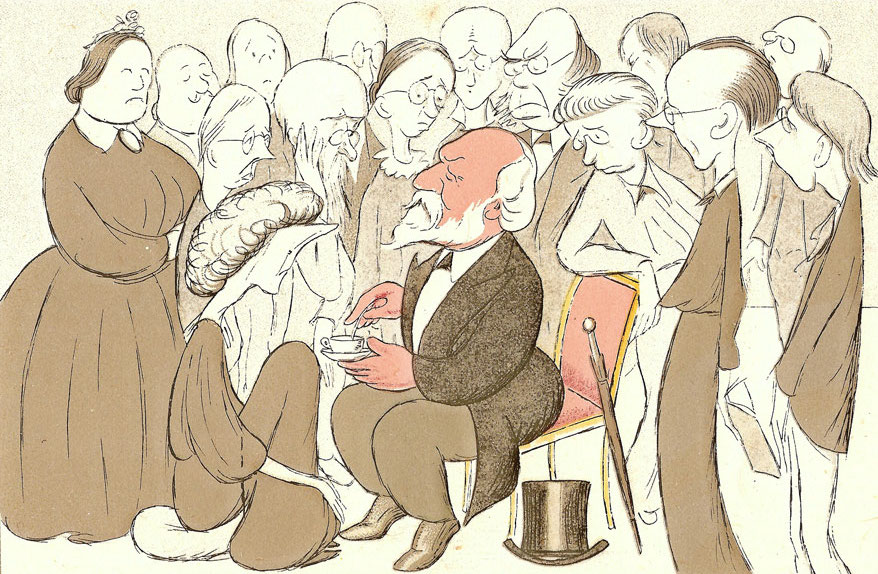

Then the reviews began, the features, festivals, and flattery, the interviews, the travel, the larger and larger advances, the requests for contributions to prestigious newspapers or quotes for the covers of other writers’ books, an interminable stream of emails and phone calls. Of course you might be able to resist all this, but even resisting would change the tone of your life. A siege mentality would ensue. And why should you resist? Why not enjoy success? Why not accept that you are a genius, if people insistently tell you that you are?

One way or another, from this point on it will be hard to achieve the same concentration, the same innocence, when you return to the empty page and the next stage in a life story that is now radically transformed. Inevitably you will be tempted to write toward what the public has appreciated, laying the guilt and shame on thick, if it was the expression of guilt and shame that the critics admired. Or, conversely, you may now find yourself deliberately refusing to give the public what they were enjoying, precisely to avoid becoming their servant, to stay in control. Either way the atmosphere you work in has changed.

In 1874, Giovanni Verga, at the time a modestly successful society novelist, was invited to write a short story about Sicilian country folk. Something of a dandy himself, a man who had abandoned Sicily to be at the heart of a more modern and mundane Italy in Milan, Verga wasn’t enthusiastic. But because he needed money to finance his fancy clothes habit he wrote a story, “Nedda,” that entirely changed his life. Essentially it is the tale of how a country girl comes to grief, falling pregnant before marriage, then loses her husband-to-be in a farm accident. “Nedda” was such a success that Verga, who now saw that he had stumbled upon something close to his heart, began a whole series of “country-folk” novellas, each more brilliantly constructed and devastatingly pessimistic than the next.

Constantly praised for the stories’ implacable social realism, and again for his use of Sicilian dialect, or, to be more accurate, a rich mix of dialect forms and regular Italian that gave readers the illusion they were hearing Sicilian voices, Verga, who was rapidly growing wealthy from his sales, began to study in academic earnest the world he had hitherto written about only from memory and with great creative liberty. He began to think of himself as some kind of anthropologist involved in a vast Zola-like project of mapping out Sicilian society.

So he wrote the considerable novels I Malavoglia and Mastro-don Gesualdo. But to read these overly long, muddled works, cluttered with detail and packed with Sicilian proverbs, is to appreciate that both the public and Verga had misunderstood the qualities of the novellas. Their success had nothing to do with any commitment to social justice. Their achievement was to fuse an apparently collective narrative voice, as if the story were told by the community, with protagonists who accept and even engineer their own downfalls, because, however scandalously treated, they have completely internalized society’s judgement of their predicaments and see nothing strange in their “punishment.” And all this happens very quickly and with a devastating sense of inevitability. So Nedda, unable to support her dying mother or feed her baby, hardly protests that her fellow Catholics are denying her charity because she had the child out of wedlock. It seems entirely normal to her. The irony that we all allow a hypocritical society to guide our most intimate judgements was something Verga struggled with in his own personal life and that he had now found a way of expressing on paper. Which makes the fact that he was himself pulled off course by public acclaim and the contemporary enthusiasm for pseudo-scientific realism all the more ironic.

Of writers like Joyce, or Pavese, or Beckett, one might say exactly the opposite. They did everything they could not to go where the public pushed them. Joyce relentlessly made things more and more difficult for readers, as if success actually prevented him from producing more of the same, so determined was he to be nobody’s servant. Hence the lucid and fluent Dubliners becomes the more difficult Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, then the far more difficult Ulysses, packed with passages that many felt were obscene, and finally, when that brought even more success, the completely indigestible Finnegans Wake. Joyce would read sections of his “Work in Progress” to friends to see how they responded; when he felt they had understood too easily, he would go make it more difficult.

Advertisement

Cesare Pavese was convinced that any literary success must mean he had compromised his principles in some way, allowed himself to be contaminated. In 1950, shortly after winning Italy’s major literary prize, the Strega, he killed himself, aged forty-one. Reading Beckett’s letters after the first productions of Waiting for Godot, one has the impression of a man determined to deny fans and critics the profound significance they are convinced must lie behind the play. His increasingly cryptic later works look very much like a reaction against success, a determination not to let the public have its much craved symbolism to as he put it, “take away with a choc-ice at the end of the performance.”

We can admire this determination not to surf a wave of public acclaim, but all the same none of these writers is isolated from the consequences of success. Their work is clearly influenced by the attention it achieved. And since many admire a writer all the more for his intransigent refusal to cozy up to the reader, this hostile reaction actually feeds the public’s interest and esteem. The more cryptic Beckett becomes in reaction to those readers after a meaning, the more he resembles the kind of author some readers are eager to adore, because meaning is always more profound when arrived at with effort. Indeed the presence of the cryptic almost guarantees the seriousness of the meaning withheld. Someone who hides has something to hide.

Among more recent authors, Philip Roth has played endlessly with the critics’ interest in the relationship between his fiction and his private life, arriving in Deception at having a character called Philip Roth announce, “I write fiction and I’m told it’s autobiography, I write autobiography and I’m told it’s fiction, so since I’m so dim and they’re so smart, let them decide what it is or it isn’t.” These are games one can only play when one’s previous work has created a certain notoriety; Roth never seemed worried that he was allowing his novels to be influenced by this noisy engagement with his own celebrity. Conversely J. D. Salinger and later Thomas Pynchon allowed celebrity to push them into long periods of silence, as if success had forced them to become austere. But whether happy to join the scrimmage or appalled by the idea of being contaminated, all these writers are inevitably changed by the reception of their work and removed from the atmosphere of their initial inspiration.

Let us add one more complication success brings: the illusion of predestination. In this regard I cannot help recalling a long conversation with V. S. Naipaul in which he insisted that he could not have failed as an author, and that recognition, even immediate recognition, of his genius was inevitable, simply because he was so good. I could not persuade him to accept that he only believed this because he had in fact been successful and that it must have been possible, given the world’s perversity, for recognition to have eluded him. The conviction of predestination came after the event.

But whatever the exact psychology of the process, the present has a way of contaminating the past. And the writing will change accordingly. Turmoil and dilemma once experienced with a certain desperation may be seen more complacently as the writer reflects that through expressing them he has realized his inevitable and well-deserved triumph. The lean years of patient toil when no one paid attention may even begin to seem preferable to the present. The very thing you created in the heat of fierce concentration has destroyed the circumstances that made it possible. The writer is devoured along with his books.