In my hometown library in rural New England—a Georgian house that had been converted to public use without in the least diminishing its shabby charm—what had once served as a dining room was now devoted to children’s books. Some furniture remained; on the bottom shelf of an enormous “credenza” (I mouthed the word), under W, I found one of the lasting treasures of my reading life in the books of Laura Ingalls Wilder. The knowledge that I was only one of a crowd of children devoted to these “Little House” stories of American pioneer life could not have altered the intensity of my personal attachment to the brave, and often surprisingly lonely, heroine, the girl Laura whose travels with her family take her from the Big Woods of Wisconsin to Indian Territory (Kansas); then to Minnesota and, finally, Dakota Territory, in the years from 1869 to 1883.

Later, I advanced to books as improbably assorted as War and Peace, Peyton Place, and Zuleika Dobson, indeed any novel whose title caught my eye. But from time to time I would return to the children’s room and furtively recapture a volume of those books about young Laura Ingalls. My favorite was On the Banks of Plum Creek, in which the family lives in a dugout in a landscape full of adventures—floods, fish, badgers, leeches, wheat farming, cattle stampedes—and barely survives a grasshopper plague. By fifteen, I was already nostalgic for Laura’s world and for my eight-year-old self who had first discovered it.

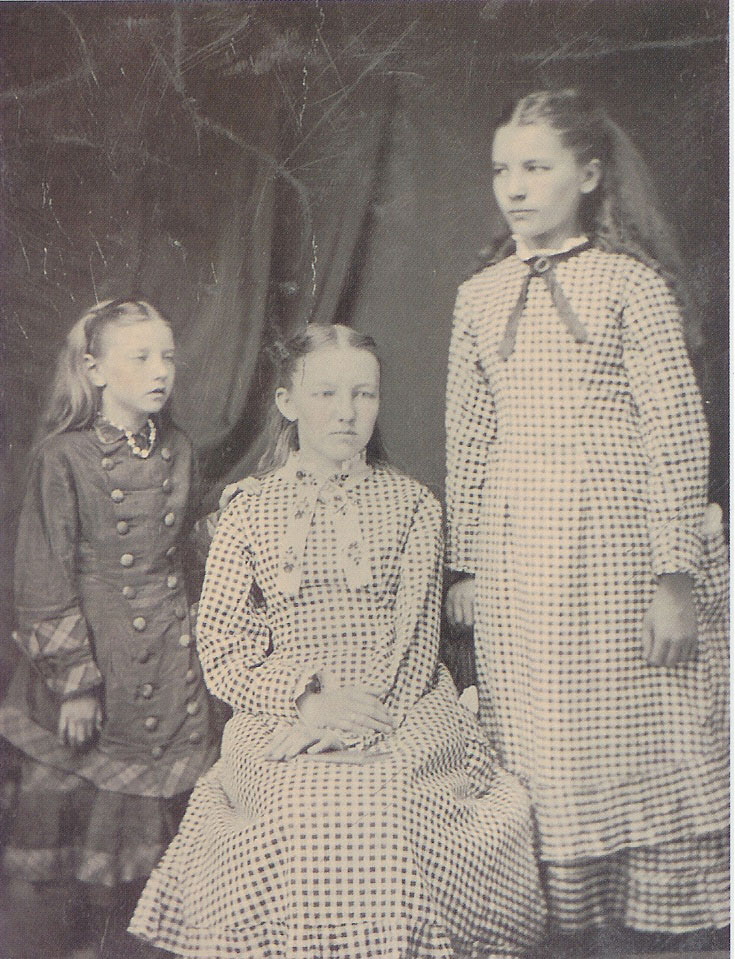

Nostalgia, with its admixture of warmth, loss, and dangerous sentimentality, suffuses any consideration of the Little House books. It’s the only way to make sense of the phenomenal popularity of the new $40 scholarly tome, Pioneer Girl—sold out at many bookstores, and going into a third printing this month. Edited by Pamela Smith Hill, it reprints the never-published original memoir (in first person, and written for adults) that Wilder wrote in 1930 when she was in her early sixties, accompanied by numerous and detailed notes, maps, and illustrations, and an excellent bibliography. With her family hit hard by the Depression, she hoped her memoir might launch her career as a writer, but publishers rejected it. From this text Wilder later mined the central anecdotes that became the Little House series, the first volume of which was published in 1932.

I learned that there has long been a full-blown Wilder industry, with branches to be found at the South Dakota Historical Society, something called the Pioneer Girl Project (producers of this volume), the Little House Heritage Trust, the Laura Ingalls Wilder Historical Home and Museum in Missouri, the Ingalls Homestead in De Smet, South Dakota, and the university presses of, among others, Kansas, Nebraska, and Missouri. Some interesting questions of historical accuracy and interpretation do arise in this volume—chiefly, for me, to what extent Wilder’s daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, edited and rewrote her mother’s prose (not nearly as much as others have speculated, is my conclusion). But the excitement over Pioneer Girl cannot be mostly scholarly; its buyers are, rather, fans. According to one estimate, more than 60 million copies of her books have been sold (and translated into more than 40 languages).

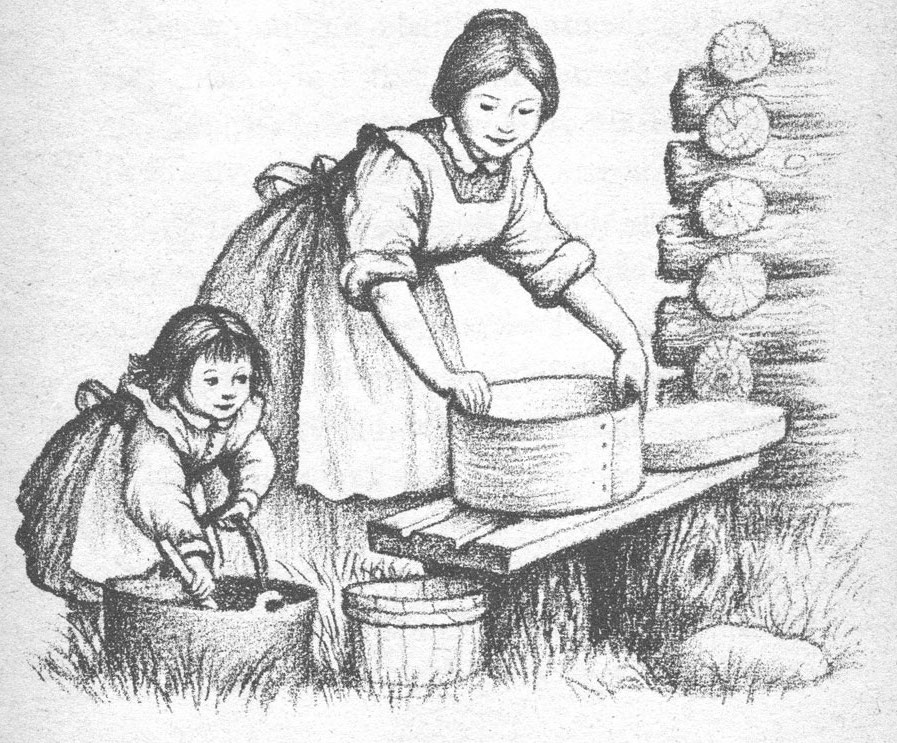

Most of those books sold, it should be noted, were not the very first editions from the 1930s, but the later 1950s editions, with illustrations by Garth Williams. His pencil-and-charcoal drawings enlarge the texts, emphasizing human, and animal, softness and warmth—the pictures in Little House in the Big Woods, when Laura is not yet five, are rounded and womb-like, in their evocation of snug happiness. Like Wilder’s texts, and like the heroine herself, Williams’s drawings mature and elongate with the series but never lose their essential softness. The slightly spikier drawings, inflected with ink, that Williams executed for Charlotte’s Web and other books provide an interesting contrast here—it is as if, under the influence of the profound nostalgia of the Little House texts themselves, Williams had misted up his own lens.

In assembling Pioneer Girl, Hall and the others have focused on texts and historical accuracy, so except for the reproduction of a few illustrations, one would never know from this volume of the significant part Williams’s drawing must play in the abiding popularity of the books that eventually evolved from the Pioneer Girl draft. Even now, rereading the Little House books, I find myself eagerly turning ahead to the pictures. They are so much more than “illustrations,” although they also fulfill that purpose admirably, especially in the passages of description of domestic tasks—the making of a door, of cheese, of maple syrup, of bullets; the plowing of land, the stitching of curtains and dresses. These homely details of pioneer life serve as fascinating reminders of the resourcefulness of ordinary men and women in those days—though we are reminded frequently that no one farmed, or built, better than Pa Ingalls; and no one cooked or sewed better than Ma. They are exemplars of American can-do ingenuity; and, crucially, of independence.

Advertisement

When making changes from her original manuscript to shape the classic tales of her children’s books, Wilder consistently smoothed the edges of her remembered stories. Many lively anecdotes, involving dozens of other characters, were jettisoned as distractions. Gone is the birth, and infant death, of a brother; gone is a back-tracking to Wisconsin, and a stay in Iowa; gone are the many times the family lived and traveled in close quarters with other families.

Curiously, Wilder did not remove from her children’s books her ambivalence about the Indians the family encountered. As a little girl, she is mostly fascinated, though also fearful. She allows us to see one of the only sources of disagreement between her parents: Pa respects, and tries to understand, the Indians—an unusually enlightened attitude, given the hostility and fear most white settlers felt; Ma feels an uncomplicated loathing more typical of the times. Because, as in most areas, Laura admired and imitated her father, more than one Indian in her stories is given a heroic role. In the second volume, an Osage chief stops a threatened “uprising” against the white settlers who have illegally come into Indian Territory. Later, in the Dakotas, another Indian stops to warn homesteaders of a coming hard winter, as he and his people are heading south to safety. Although certainly Wilder’s westward story participates in many ways in the larger, politically fraught myth of Manifest Destiny, her wondering interest in and affection for the Indians, both in the memoir and in her children’s tales, complicates it at the same time.

Simplification, however, is Wilder’s usual choice; and in The Long Winter, the seventh book in the series, we read the harrowing, memorable tale of the winter of 1880-1881 (the one the Indian warned about), which in the Dakotas brought many blizzards from October through April, blizzards that stopped the trains with their food and fuel supplies and led to the freezing and starvation of livestock and homesteaders. Wilder makes of this epic winter an extraordinary story of survival—her family resorts to twisting hay to make “logs” and grinding wheat seed to make bread and gruel. Although, at personal peril, two young men of the town do travel with make-shift sledges to secure wheat to keep the townspeople from starving, the main story of that long winter stays by the barely-warm stove of the Ingalls family. There, huddled beneath blankets, they grind wheat in a coffee mill and sit in the dark all day long to save kerosene, trying to keep one another’s spirits up with stories and songs.

What Wilder removed from her actual history, as recounted in Pioneer Girl, was the presence of another family, a couple and their baby, who were in the house with them all during that long winter, indolent moochers who infuriated the young Laura (thirteen at the time) with their selfishness. One can easily understand the wise fictional decision to focus and intensify the story of survival by removing these extraneous characters—but that decision also makes it much easier to celebrate both independence and goodness, freed from the tangle of interdependence and bad feelings. It assists as well the impulse to nostalgia.

Nostalgia prompted Wilder, when in her 60s, to recreate her past and especially to commemorate her beloved parents. Most of the books, and many of the chapters within the books, end with the family gathered by the “fireside” (almost always a stove or a lit lamp) listening to Pa play his fiddle. The family sings the old songs, many of them hymns. Did ever such a family exist? It seems, according to the account in Pioneer Girl, that it really did, and in some only slightly more complicated fashion that Wilder’s later fiction depicted. To many readers, even today, Wilder paints an almost irresistible picture of a traditional family, with its stern-but-gentle patriarch and matriarch teaching their children the importance of obedience and charity, and with its hard work and simple pleasures and ties to the land. We are not inclined to ask: Where did the Indians go? What did plowing up the prairie do to the ecosystem? How could women bear to be so well-behaved? Who built that railroad? Even as adult readers, our nostalgia can flood our common sense, making us resist such questions and their answers.

Advertisement

Another great danger of sentimental nostalgia is that it can bring the bitter taste of a lost paradise, and with that bitterness, a sense of grievance against what has replaced it. Most cults, and most tyrannies, thrive on nostalgic grievance—it is their life’s blood; and so my own affection for these books must be tinged with a wariness brought on by that unpleasant thought. There is no rest for the wicked, as Ma might say.

Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Biography is published by South Dakota Historical Society Press.