From a passage in W, or The Memory of Childhood, readers have long known that Georges Perec’s “first more or less completed novel” dealt with a famous painting by the Renaissance artist Antonello da Messina, the Portrait of a Man known as Il Condottiere (1475). However, no such novel was published in Perec’s lifetime. When I started to gather material for a biography of the writer a few years after he died in 1982, there was no trace of it in his surviving papers. Like other early titles listed in the “autobibliography” that Perec compiled in 1989 for the literary magazine L’Arc, the “Antonello novel” was missing.

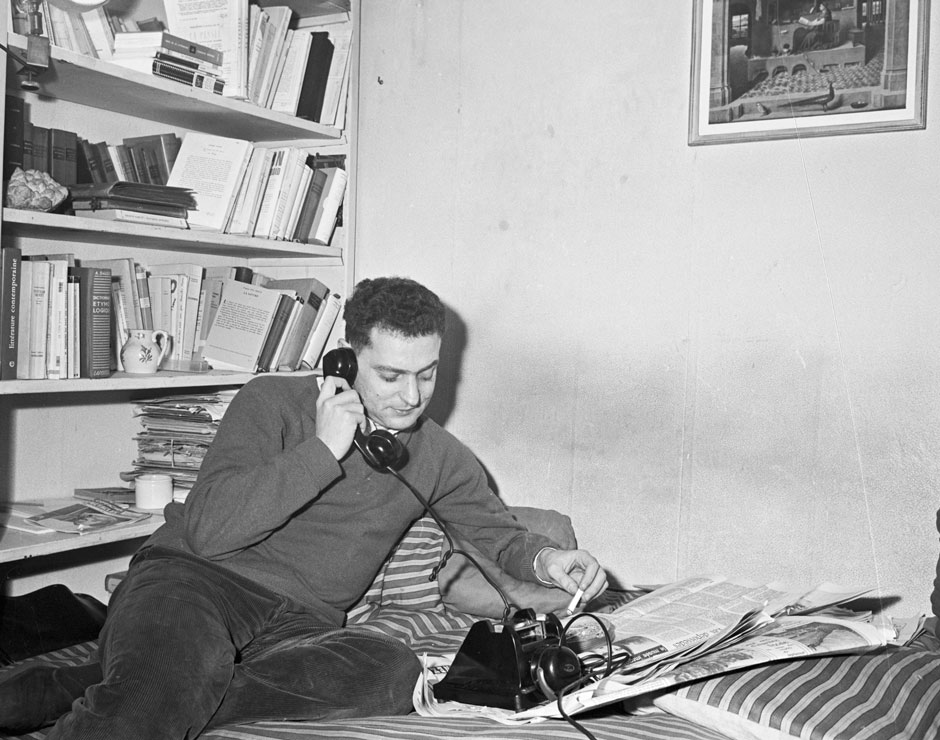

Old friends of the writer and the letters they’d kept and allowed me to read soon told me what had happened to these unfindable works. Georges Perec, born 1936, published his breakthrough novel, Things, in 1965. Perec, who had a poorly paid day job as librarian in a medical research laboratory, suddenly found himself a literary celebrity, and in a position to leave his thirty-five-square-meter perch in Rue de Quatrefages for a larger home in Rue du Bac. Preparing for the move in spring 1966, he stuffed redundant paperwork into a cardboard suitcase intended for the dump, and put his literary papers in a different case of similar appearance. In the move, the wrong case got junked. All of Perec’s manuscripts and typescripts prior to the writing of Things disappeared.

The story led me to expect I would never get to read those lost works. What I set out to do as Perec’s first biographer was to talk to as many people as I could who had known the writer during his tragically short life. When I’d already drafted the first part of Georges Perec: A Life in Words, there were only a few names left on my list, and I didn’t expect that they would add much to the wealth of information that Perec’s many other friends had already shared with me. Following up the remaining leads that I had, I went to dine with a former journalist who’d met Perec at the Moulin d’Andé, the writer’s retreat in Normandy that was Perec’s second home in the later 1960s. Toward the end of the evening, as I was looking for an opportunity to make my escape, Alain Guérin let it out that someone had once given him one of Perec’s pieces to look at. He didn’t know if it was of any interest. Could I perhaps tell him what it was? Guérin went to a wardrobe, pulled out a manila envelope and handed it to me.

There it was: 157 carbon copy sheets of flimsy paper beginning: georges perec le condottiere roman (e. e. cummings–style lowercase was fashionable among the French avant-garde in those days). I told Guérin it was immensely precious—but could I please take it away to read? With great generosity he allowed me to do just that, and I stayed up all night reading Perec’s “first more or less completed novel” in bed. It was really hard to follow—I put it down to the late hour, the smudgy carbon and the dim hotel lighting. But before my bleary eyes finally shut, I knew that I had in my hands the unhoped-for revelation of the tangled roots of Perec’s later creation and of the masterwork that crowns it. It was connected by a hundred threads to every part of the literary universe that Perec went on to create—but not like anything else that he wrote.

The story isn’t particularly elaborate. Gaspard Winckler, born around 1930, is dispatched by his well-to-do French parents to a boarding school in Switzerland during the war. A young and wealthy idler with a good eye and outstanding manual skills, he falls in with a painter called Jérôme, who trains him to become a high-class forger of artworks of every kind. Winckler breaks off relations with his family, acquires qualifications in art restoration and a dummy job in a museum to cover his tracks, and then spends twelve years in well- remunerated employment faking coins, jewelry, and oil paintings ranging from Renaissance Madonnas to Impressionist landscapes. Anatole Madera, the head of the international gang of dealers that trades Winckler’s output, then asks him to use a wooden panel painted by a minor Renaissance figure to forge a new masterpiece by someone sufficiently famous to command a very high price.

Winckler selects Antonello da Messina as his target, for financial, art-historical, and personal reasons. However, he conceives of the commission as the ultimate challenge. He aims not to pastiche an existing portrait, but to make an entirely new one that would be accepted as an Antonello by buyers and experts and would also be a work of art in its own right. A work devoid of artistic merit could hardly be seen as an Antonello, of course; but Winckler’s ambition is to create something that is simultaneously Antonello’s and his own authentic creation. Predictably, the result falls short of such a high mark. Rebelling against a failure he’d set up himself, Winckler cuts Madera’s throat. Perec’s account begins at this point when, having murdered his paymaster, Winckler finds himself trapped in a basement studio. He tunnels his way out, and returns to Yugoslavia to tell his story once again to Streten, an old (and apparently older) friend. That’s it. We never learn what happened next.

Advertisement

The story is told twice: first, as an internal monologue, in a bewildering variety of stream-of-consciousness techniques, while Winckler digs himself out of Madera’s house at Dampierre, in the countryside near Dreux (Eure-et-Loir), about an hour from Paris; then in speech, in a Q & A session halfway between police interrogation and psychotherapy. Perec often returned to the formal idea of the two-part work: W, or The Memory of Childhood has alternating chapters that tell apparently different stories, and his unfinished detective novel, “53 Days,” was designed to have a second part that would undo everything set up in the first. In both narrations of Gaspard Winckler’s plight, murder is presented as the key to liberation. It’s the means by which Winckler can cease to be a fake artist in both senses of the phrase—as a maker of fakes, and as a false artist. Mortal violence is what he needs to begin to be himself.

Perec’s education in visual art began among the Yugoslav group he attached himself to in Paris around 1955, of which the most striking trace is a portrait of Perec by the Serbian artist Mladen Srbinović. It continued apace among the young intellectuals who formed Perec’s second circle in the later 1950s and with whom he sought to launch a new cultural periodical under the title The General Line (which never appeared). Alone and with friends, Perec visited exhibitions and galleries in Paris and made a trip to Berne to see a large collection of works by Paul Klee. But the Antonello portrait that hangs in the seven-meter gallery in the Louvre was a special favorite, for a quite peculiar reason.

Like his hero Gaspard, Perec had been at a boarding school in the Alps during the war, where he was taught to ski. Around the age of eight or nine, he had an accident in the changing room:

One of my skis slipped from my hand and accidentally grazed the face of the boy putting his skis away next to me and he, in a mad fury, picked up one of his ski-sticks and hit me with it on the face . . . cutting open my upper lip.. . . The scar that resulted from this attack is still perfectly visible today.. . . It became a personal mark.. . . It is this scar, also, which gave me a particular preference . . . for Antonello da Messina’s Portrait of a Man known as Il Condottiere.

—W, or The Memory of Childhood, p. 108

The scar on the ancient canvas is not much like the graze on Perec’s upper lip (one is dead center above the lip, the other to the left and bisects the lip itself). I suspect that the reason given by Perec covers another and perhaps more important one. Most postcard reproductions of the Antonello portrait show only the face of the unknown sitter (whether he really was a condottiere, a leader or warlord, or just an accountant or a chum is a matter of conjecture). However, Antonello also painted a false frame at the base (but not on the three other sides), and on it he depicted a strip of folded paper bearing the Latin inscription Antonellus Messaneus me pinxit: “Antonella of Messina painted me.” The cartellino or caption panel also says without saying that Antonello also painted “Antonello painted me”: a self-confirming loop that indirectly but no less clearly asserts the artist’s ownership of his work.

Perec was a modest and unassuming man in real life, but in his art he was at least as self-assertive as his Renaissance model:

He would be in the painting himself in the manner of those Renaissance painters who reserved for themselves a tiny place in the crowd of vassals, soldiers, bishops and burghers; not a central place . . . but an apparently inoffensive place . . . as if it were only supposed to be a signature to be read by initiates, something like a mark which the commissioning buyer would only just tolerate the painter signing his work with.. . .

—Life A User’s Manual, p. 226

Winckler’s dilemma is this. However perfect it is from a technical point of view, a painting cannot be a forgery and an authentic work of art at the same time. He sets out to achieve the impossible feat of creating a real masterpiece that will be recognized (and therefore purchased) as a genuine Antonello. But by the very fact of his success in “painting like Antonello,” Winckler, like Antonello before him, produces an authentic image of his own true self—an evasive, indeterminate fraud of no fixed identity. The more “like” the process is, the less “like” the product can be. He’s cooked. He’s done for. He’s finished. Perec doesn’t explain the argument of his novel half so clearly because he wants to take his readers through the process by which a false artist comes face-to-face with the truth of art. This is a novel, not an essay. Almost.

Advertisement

Superficially, Portrait of a Man isn’t like any of Perec’s later works, but just as significantly it isn’t much like any other French fiction of the 1950s either. The nearest though still distant analogue to it is Michel Butor’s Modification (1957), which uses the second-person form of address to re-create the process by which a man becomes aware of where his future path lies. All Perec’s later work is in constant and intense dialogue with literary tradition; but Portrait of a Man engages with the matter of writing indirectly, through the tangled concepts of authenticity and the real as they can be articulated in pictorial art.

After adding a chapter about the novel to my biography of Perec, I returned the precious typescript to Alain Guérin, who later placed it in a public collection. A second carbon copy was then found among the papers of another one of Perec’s friends of the 1950s. With the discovery of other texts believed lost in the move from Rue de Quatrefages and the publication of substantial parts of Perec’s correspondence from the 1950s, a fuller, richer picture of “Perec before Perec” began to emerge. But there was understandable reluctance to publish his juvenilia. That’s what happens to writers thoroughly dead and gone. Perec may have passed away in 1982, but his work and his personality remained a living part of contemporary literature for many decades after that. And still today.

In this respect Portrait of a Man is an exceptional text. It’s true it was rejected and then lost, but it certainly doesn’t belong to the category of “teenage experiment” or “youthful folly.” It wasn’t dashed off in a burst like L’Attentat de Sarajevo, nor was it left incomplete. It’s the result of a process of drafting and revision that lasted around three years, before, during, and after Perec’s military service in a parachute regiment. In 1958 a version called Gaspard pas mort (“Gaspard Not Dead”) was submitted to a publishing house that turned it down, but an editor at France’s most prestigious literary publisher, Gallimard, got to hear of it. He was sufficiently impressed to issue a contract in 1959—with an advance on royalties, to boot! But he thought it not quite ready for publication, and asked Perec to revise it.

On his release from the military in December 1959, Perec set to work, and when he’d finished rewriting it one more time eight months later, he was so thoroughly exhausted with his condottière that he wrote ENDENDENDEND across a whole line on the last page, followed by a warning in uppercase:

YOU’LL HAVE TO PAY ME LOADS IF YOU WANT ME TO START IT OVER AGAIN. Thursday, August 25, 1960.

He was in a hurry to finish because he was about to leave for Sfax, in Tunisia, where his wife Paulette had got a job as a teacher under a cultural cooperation scheme between France and its former protectorate. The dreadful news came in a letter from Gallimard just a few days before they left Paris. Having read the new version, they preferred not to proceed with the contract. Perec did not need to return the advance.

The blow nearly knocked the young writer off his perch. The months that followed were among the gloomiest in all Perec’s adult life. But he picked himself up, and began several new projects before alighting on the path that would lead him to Things. As he wrote to a friend in 1960, “Best of luck to anyone who reads [my novel]. I’ll go back to it in ten years when it’ll turn into a masterpiece, or else I’ll wait in my grave until one of my faithful exegetes comes across it in an old trunk you once owned and brings it out.” Perec me pinxit, I suppose.

From Portrait of a Man Known as Il Condottiere

by Georges Perec

He didn’t know much about real life. His fingers brought forth only ghosts. Maybe that was all he was good for. Age-old techniques that served no purpose, that referred only to themselves. Magic fingers. The relationship between the skills of a Roman jeweller, the knowledge of a Renaissance painter, the brushstroke of an Impressionist and the patiently learned capacity to judge what substance to use, what preparation was required, what agility to develop—that relationship was merely a matter of technique. His fingers knew. His eyes took in the work, divined its fundamental dynamic, split it down to its tiniest elements, and translated them into what for him were internalized words such as a more or less liquid binding agent, a medium, a backing material. He worked like a well-oiled machine. He knew how to lead the eye astray. He had the art of combination. He had read da Vinci and Vasari and Ziloty and the Libro dell’Arte; he knew the rules of the Golden Ratio; he understood—and knew how to create—balance and internal coherence in a painting. He knew which brushes to use, which oils, which hues. He knew all the glazes, supports, additives, varnishes. So what? He was a first-class craftsman. Out of three paintings by Vermeer, van Meegeren could create a fourth. Dossena did the same with sculpture; Joni Icilio and Jérôme likewise. But that wasn’t what he’d been after. From the Antonellos in Antwerp, London, Venice, Munich, Vienna, Paris, Padua, Frankfurt, Bergamo. Genoa, Milan, Naples, Dresden, Florence and Berlin could have arisen with admirable obviousness a new Condottiere rescued from oblivion by an amazing find unearthed in some abandoned monastery or castle by Rufus, Nicolas, Madera or another one of their associates. But that wasn’t what he wanted, was it?

What was the illusion he had cherished? That he would be able to cap an untarnished career by carrying off what no forger before him had dared attempt: to create an authentic masterwork of the past, to recover in palpable and tangible form, after a dozen years’ intense labor, something far above the technical tricks and devices of his trade such as mere mastery of gesso duro or monochrome painting—to recover the explosive triumph, the perpetual reconquista, the overwhelming dynamism that was the Renaissance. Why was that what he’d been after? Why had he failed?

What remained was the feeling of an absurd undertaking. What remained was the bitterness of failure; what remained was a corpse. A life that had suddenly collapsed, and memories that were ghosts. What remained was a wrecked life, irreparable misunderstanding, a void, a desperate plea . . .

Now you’re on your own and you’re rotting in your cellar. You’re cold. You can’t make sense of it any more. You’ve no idea what happened. You’ve no idea how it happened. But the one who’s alive is you, here, in this same place, you at the end of twelve years of a featureless existence, an existence pregnant with nothing. Every month, every year you dumped your packet of masterpieces. And then? Then nothing . . . And then Madera died . . .

Arm raised, the glint of the blade. All it took was a gesture. But first he had had to get the razor out of its sheath, check its condition, fold it in his palm so he could use it, leave the laboratory, climb the stairs one by one. One after another. Slowly. At each step the aim became more precise. What was he thinking about? Why was he thinking? He was perfectly aware: he was climbing the stairs to go and slit Anatole’s throat, the throat of the late Anatole Madera. The thick fat throat of Anatole Madera. His left hand would be wide open to provide a better grip as he applied it firmly and speedily to the forehead and pulled it backwards, and his right hand would slit the man’s throat with a single thrust. Blood would spurt. Madera would collapse. Madera would be dead.

The essay by David Bellos is adapted from the introduction to his new translation of Georges Perec’s Portrait of a Man Known as Il Condottiere, published this week by the University of Chicago Press.