To kill or capture? That is the chilling question that US officials—and even members of Congress—reportedly ask behind closed doors these days, as they consider how best to deal with potential terrorist threats abroad. A New York Times account of the capture of a US citizen suspected of involvement in al-Qaeda suggests that the debate surrounding such decisions may be more robust than many had thought. At the same time, the story’s sparse details, all obtained from anonymous officials, underscore how little transparency there continues to be about the president’s targeted killing program.

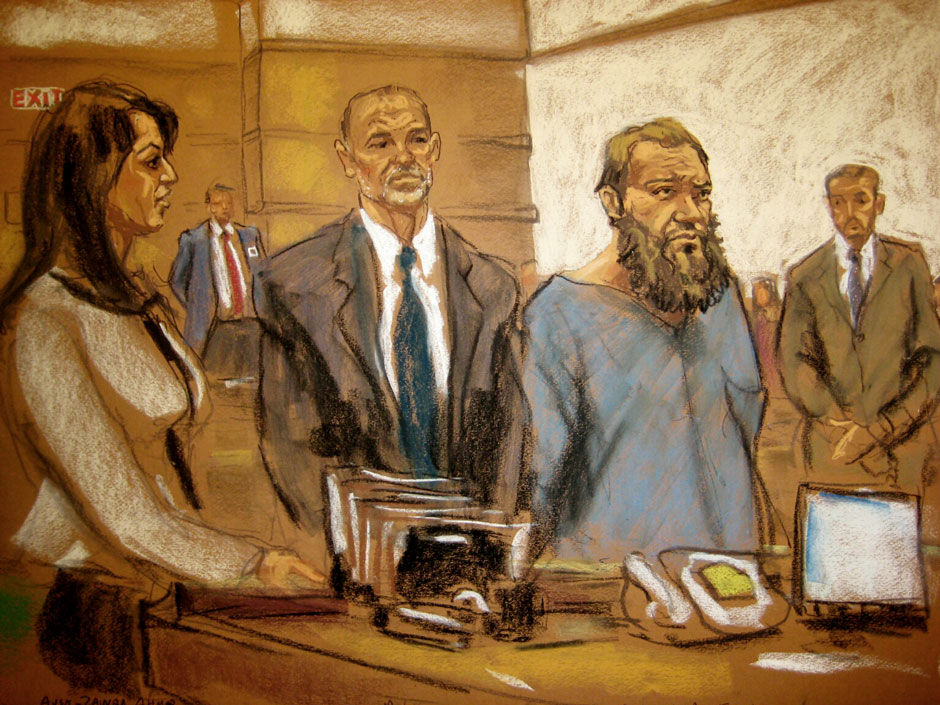

The case involves Mohanad Mahmoud Al Farekh, a twenty-nine-year-old US citizen born in Texas but raised in Jordan and Canada, who is believed to have left Canada for Pakistan in 2007, allegedly to train with jihadist groups affiliated with al Qaeda. If the CIA and Pentagon had had their way a couple of years ago, he would have been summarily killed with a drone strike in Pakistan. Instead, he was captured by Pakistani forces and handed over to the United States, where on April 2, he was indicted in a federal court in Brooklyn for conspiring to provide material support to terrorists. The fact that parts of our government wanted to kill, without a trial, a citizen who, even if convicted, will face a maximum of fifteen years in prison, illustrates the dramatic divide between the military and law enforcement models for addressing terrorism.

From what is suggested by the Times report, Attorney General Eric Holder and other Justice Department officials deserve credit for saving Al Farekh’s life. The United States had been actively monitoring Al Farekh in the tribal areas of northwest Pakistan at least since 2012. By early 2013, both the CIA and the Defense Department requested approval to put him on a “kill list” of terrorism suspects. According to guidelines adopted by the White House that spring, President Obama will authorize a targeted killing outside Afghanistan only if (1) an individual “pose[s] a continuing and imminent threat to the American people”; (2) “there are no other governments capable of effectively addressing the threat”; (3) capture is infeasible; and (4) there is a “near-certainty that no civilians will be killed or injured.”

The CIA and Defense Department claimed Al Farekh met these standards. And in a closed hearing in July 2013, so did Michigan Congressman Mike Rogers, chair of the House Intelligence Committee, who apparently railed against the administration for not killing Al Farekh, claiming that “We’ve never seen a bigger mess.” But Justice Department officials doubted whether Al Farekh posed an imminent threat, whether he was a high-level al-Qaeda leader, and indeed whether his capture was infeasible. As a result, the authorization to kill was not granted.

The Justice Department was right. Evidently Al Farekh’s capture was feasible after all. And the rather routine terrorism charges he now faces suggest that the Justice Department’s doubts about the gravity of the threat he posed were also warranted.

In providing a glimpse of the administration’s internal debate about a possible targeted killing of a US citizen, the Brooklyn case points to the many questions about the program that remain unanswered. Here are some:

- Where do members of Congress get authority to advocate for the killing of American citizens? Mike Rogers didn’t get his way, but why should he even have a say in the execution of an American citizen?

- Why did both the CIA and the Pentagon believe that Al Farekh could not be captured, when events proved that in fact he could? Does the availability of military technology that allows us to kill remotely affect how “feasible” we deem a capture? After all, before the advent of drones, when the alternatives to capture were to send troops into a foreign country or to drop a bomb, with inevitable collateral damage, the threshold for authorizing force was presumably quite high. When one can use a pinpoint strike with a drone, executed with plausible deniability and covert consent from Pakistan, does that cause the intelligence and defense agencies to redefine “feasible,” allowing for a lighter trigger for the decision to kill? As a legal matter, it shouldn’t. As a pragmatic matter, it very likely does.

-

How urgent could the threat posed by Al Farekh to the United States have really been if two years later, we were able to capture him and arraign him in an ordinary federal court in Brooklyn? The concept of “continuing and imminent threat” has always seemed an oxymoron. For a threat to be imminent, it should be immediate; the purpose of this requirement is to ensure that lethal force is truly a last resort. But Anwar al-Awlaki, the American citizen killed by a US drone strike in Yemen in 2011, was reportedly on the kill list for more than a year before he was actually killed. And there is no evidence that Al Farekh engaged in any attacks against the US in the two years between the time officials requested kill authorization and his capture in Pakistan. The administration argues that when terrorists hide among the civilian population and threaten to attack without warning, the requirement of “imminence” needs to be relaxed. But if the threat “continues” for years, can it really be said to be “imminent?”

-

Would the Justice Department have raised doubts about a kill authorization if Al Farekh had been a foreign national? The Times quotes an unnamed former senior official who explained that, “Because he was an American citizen, we needed more information. Post-Awlaki, there was a lot of nervousness about this.” The Awlaki killing prompted substantial questioning of US drone policy. The notion that the president could, without any external checks whatsoever, order the killing of one of his own constituents, far from any active battlefield, was understandably disturbing to many Americans.

Advertisement

But remote-control killing without trial away from battlefields should be disturbing regardless of the passport the victim holds. Was the same scrutiny applied to the hundreds of noncitizens the Obama administration has killed with drone strikes, many of them also far from any battlefield? President Obama’s announced criteria for killing do not on their face distinguish between US citizens and noncitizens. Yet according to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, [more than 2,400 people] (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/01/23/obama-drone-program-anniversary_n_4654825.html), virtually all foreign nationals, were killed by drone strikes in Pakistan alone during the first five years of the Obama administration. Captures have, by contrast, been very few.

-

Finally, how reliable is the government’s claim that it authorizes drone strikes only when there is “near certainty” that civilians will not be killed or injured? A new study by the Open Society Justice Initiative casts serious doubt on it. The study examined nine strikes in Yemen, including four since that standard was announced, and found civilian casualties in every one of them. In total, it concluded, twenty-six civilians were killed, including five children, and thirteen others were injured. In the four strikes that post-date Obama’s announcement, eight civilians were killed. The administration, however, has made no effort to account for the number of civilians it has killed. National Security Council spokesman Ned Price’s unhelpful response to the OSJI response was that the US is “not in a position to comment on specific cases.”

Obama administration officials have shown some recognition that more public information about drone strikes is needed. In a series of speeches beginning with a 2010 address by Harold Koh, then legal advisor to the State Department, the administration has moved, if at a glacial pace, in the direction of greater transparency. This past week, the Defense Department General Counsel Stephen Preston took that effort one step further, providing important clarification regarding the administration’s legal theories for its use of force in Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, and elsewhere. Preston ended his speech with an acknowledgement of the importance of openness:

Transparency to the extent possible in matters of law and national security is sound policy and just plain good government. As noted earlier, it strengthens our democracy and promotes accountability. Moreover, from the perspective of a government lawyer, transparency, including clarity in articulating the legal bases for U.S. military operations, is essential to ensure the lawfulness of our government’s actions and to explain the legal framework on which we rely to the American public and our partners abroad.

Preston is right about the imperative for more openness; the only thing more troubling than the power to kill is the power to kill in secret. But the many unanswered questions around the case of Al Farekh show that the administration has not yet come close to satisfying that requirement. As long as we must rely on news reports based on unnamed officials’ accounts of secret meetings for our understanding of how the drone policy actually works, we do not have the information we need to judge its legality. We have no idea what “feasibility of capture” or “continuing and imminent threat” actually mean. We do not know how many civilians have been killed. And we don’t know how or whether the administration’s standards differ for the killing of US citizens and everyone else. Until we do, the administration is failing to provide the accountability that democracy demands.