Nadja Tesich, the star of Eric Rohmer’s 1964 short film Nadja à Paris, originally wrote this essay in the 1990s, but never published it. In the last three months before she died in February 2014, I helped Nadja revise the piece, recording her thoughts and our discussions. —Lucy McKeon

Occasionally, unintentionally, triggered by a smell or an old tune, my mind drifts to that time when Paris didn’t resemble the USA at all, when life on the street and screen was similar and our days appeared like the films of the nouvelle vague. There was something breezy about reasons then, why you did this or that, no clear motivation or Hollywood endings. Of course there were American films around but many were quite good, nothing like the bang-bang violence we now dump all over the globe. Those films didn’t crush or overwhelm others in quantity (a reason why they were so admired) and you could also see French, Italian, Polish, Czech, or Russian films any time. There was a cinematheque, which for students was one franc.

Most of us were poor and so we worried about three essentials—a room, the student restaurant, and a subway card. The cafés were livelier then, full of intrigue and gossip. You studied there, met friends, ate, drank—and whoever had more at the time paid. They were our living rooms in a way, convenient, warm places with a telephone, all for the price of a cup of coffee. I was in love with Paris, either what it was or what it suggested. It was still a nineteenth-century city, gray, slow-moving, with people at the center. We strolled, we looked at each other carefully, and nobody talked much about the future.

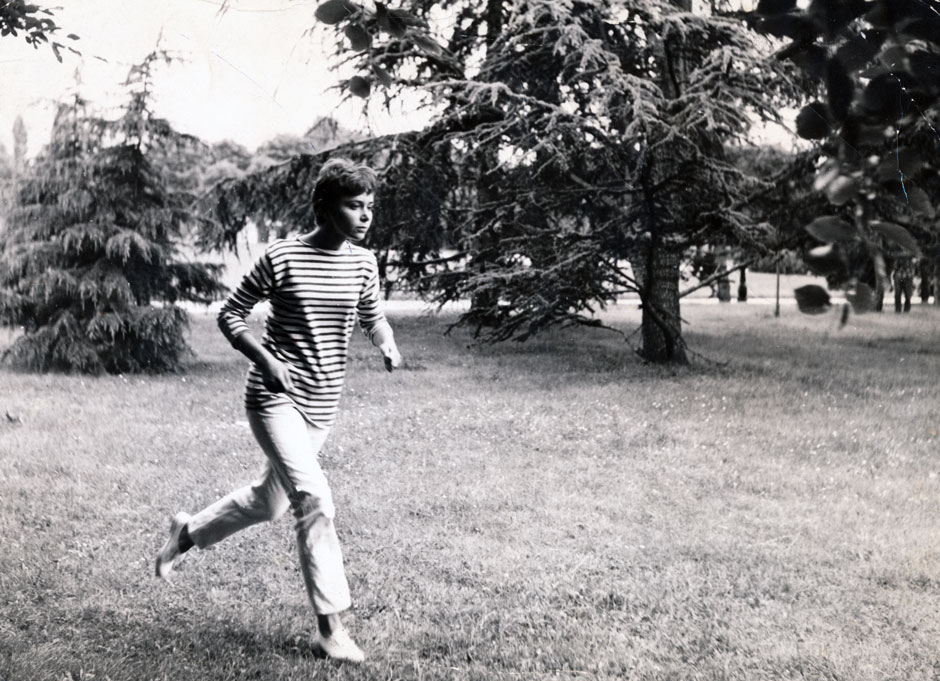

When I attempt to describe my years in Paris, no one believes me, I can tell. It was too Hollywood-dream perfect. Here is Nadja coming out of the student restaurant, minding her own business, and who should appear next but Eric Rohmer who stops her (“Why you of all people?” they ask) and within minutes he wants to make a film about her life. “What were you wearing?” is a standard question. My answer doesn’t make them happy: blue jeans, a shirt, white sneakers, no makeup, very short hair—so short that some sweet old people often referred to me as mon fils, my son. A sixteen-year-old boy is what I looked like, apparently.

When I tell them next that I was not interested in his offer because I had plans to hitch to Greece the following week, they laugh, they snicker. A likely story. But why should I have been impressed? I had no idea who this tall blond man was, he wasn’t the Eric Rohmer yet, and maybe I wouldn’t have been impressed even if I knew. In my eyes, he belonged to a sad world of grown-ups, a married man with children.

“Why you of all people, what was so special about your life?” they repeat. “No idea,” I say. Maybe because I was not interested, I used to think, until he told me how he liked my stories about Paris, how I described people on the street, their eyes adjusting like a lens when they met each other.

I was madly in love with Paris and he had received a small sum from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to make a film about foreign students in Paris. That’s it. Of course we liked talking with each other from the beginning, in spite of our differences—age, background, etc. He said we were very much alike, strange since he struck me as a bourgeois of sorts, while I considered myself doomed and displaced. In spite of his obvious intelligence, Eric didn’t have coherent political views. He never used words like exploitation or capitalism. I said yes to him because I was penniless and he offered me money—the same sum (either $200 or $400, I can’t remember) to all involved: cinematographer Néstor Almendros, the script girl and me. It meant I could pay for my dorm, eat for a few months, buy a pair of shoes. Greece will always be there, I decided.

I don’t know if Néstor was poorer than me or not. Probably the same. After Nadja à Paris his luck changed and he would go on to shoot many of Rohmer’s films, and eventually got an Oscar for Days of Heaven. Still, at that time, he was just a refugee Cuban who didn’t look Cuban but Spanish—tall, reserved, with a shyness that bordered on fear. He longed for a seersucker jacket, washable and weightless, I remember. I sent him one from my first salary. I knew nothing about him except that he had shot a documentary film in Cuba, his country that he hated. Néstor was gay, but this was not a problem for anyone except him. We accepted it, then forgot it, just like you accept that some prefer mountains to the sea.

Advertisement

Rohmer was poor too, in spite of being an adult. His apartment was tiny and he wore the same thin jacket in shades of blue-gray. The production company (Barbet Schroeder and Pierre Cottrell, who were around twenty-five at the time) was inside Barbet’s mother’s apartment. Néstor’s camera was an antique job you don’t see anymore, with one hundred-foot rolls. You just wound it up every so often and hoped it would keep constant speed. We recorded sound later on.

We wandered around Paris, the four of us. I was so poor I had to borrow a dress, a skirt, and a pair of sandals so we would have some variety in the shots. Since it was a film about me, I led the way, and introduced Eric to the working class neighborhood of Belleville and, near it, Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, a large almost empty park without the usual French statues. Eric didn’t rush, we ate pastries, days of talking, I don’t remember about what. It was summer, and we filmed the warm rain.

The production company paid for our big lunches and the wine. All of us were thin, in one shot I look drunk. At the Café Coupole, we stole some shots pretending it was a home movie. In front of the Flore, Rohmer said, “Just walk and imagine you are looking for someone.” I don’t think documentary is Eric’s forte; he would forget the truth for the sake of mise en scène. When he didn’t like the way my room looked, an American dorm in ugly red brick, he exchanged it for another: German, modern with clean lines. It was fine by me. I only objected when he told me how to react to my leg in the water. “Shiver,” he said, “Make a face.” I said no, I wouldn’t do that. I never did any of those exaggerated feminine gestures, I never giggled either.

Néstor surprised us at the screenings—his camera was so steady you couldn’t even tell it was handheld. Even I could tell he was more than gifted. The editing I didn’t like, and I remember thinking, Why did they throw away all the best shots? Narration we did in the studio later on as the film rolled. Nobody in Paris believed I wrote it, or they said he twisted my arm because this film sounded just like Eric. They said, “He too preferred cakes to a real lunch.”

I lived with Néstor after filming. He snuck me into his apartment, which was not really his. A well-known writer had left it to him for two months. We didn’t dare misplace an ashtray, we cleaned all the time. Néstor took pictures of me, and decided I should be an actress and that my pictures should go to Godard because I resembled Jean Seberg. When I went to see Godard on Champs-Élysées, his secretary said he was not there. She told me I could wait, that eventually he was bound to appear. She went out for lunch, I waited, grew bored, and fell asleep on the large, comfortable couch in the waiting room. I would have slept more if Godard hadn’t appeared, looking terrified. “Who are you?” he kept shouting. He frightened me. I ran. I don’t remember if I gave him those pictures, or if they got lost in the commotion.

Soon after that day, everything gets murky, fuzzy in my memory of the following months. I can’t even remember if I went to Greece that year. I had no money to stay in Paris another year. How would I know in March that I would become an actress in June? How will I live without money? Where will I live if I can’t pay for my dorm? These thoughts ticked in my head daily.

“How come you didn’t stay?” is the question people ask me more than any other, the one that troubles them, and that used to make me sad. One party determined it all. Rohmer was gone by then, and with him, the unwritten rule of conduct everyone had followed toward me. Eric was not a party person or a café person, he had a low tolerance for certain business people, for the nouveaux riches. He wouldn’t have gone to that party.

I don’t know whose party it was or who invited me but it was different from others that month—in a large apartment with many rooms, everything in white decor, full of starlets, producers, or some sort of money people. Sleek, rested, well dressed, and they resembled each other even though one heard different languages.

Advertisement

Somewhere in the midst of chatter, laughter, sound of glasses, my eyes focused on what appeared an Antonioni—a girl in a black strapless dress was trying to do a strip tease of sorts, everyone clapping, voices shrill. It was all civilized and in good taste, yet forced. Someone said she was an actress or a model, one of those things. Then, in a long shot, I watched, as men and girls drifted toward different rooms. The girls were so young. And as I watched all of this, I saw myself, too, in my blue jeans and sneakers, watching them.

I was aware, then, that a bold guy in a dark suit was whispering in my ear something or other, and I remembered other recent offers at other parties. Relax, don’t worry about a thing. You can stay here any time. Why don’t we go to Spain. How silly of me. It was not for free. I had to pay. I was invaded by fear. Go run, fast, I thought. If you don’t leave soon you might become someone you don’t want to be.

My blue jeans had not bothered me before that party, but I knew the time would come when they would. I couldn’t pursue “my career” this way. Where would I find the money for dresses, cabs, haircuts, make-up when I could barely pay for my student meals? I was afraid because I wanted it so badly that I might even go off with one of those men. For someone else it might have been easy. I liked myself just the way I was.

A job offer from Rutgers University came the following week, to teach film and French literature, and I took it. What else could I do? Every single detail about my departure is missing, has been wiped out, erased. I have no record.

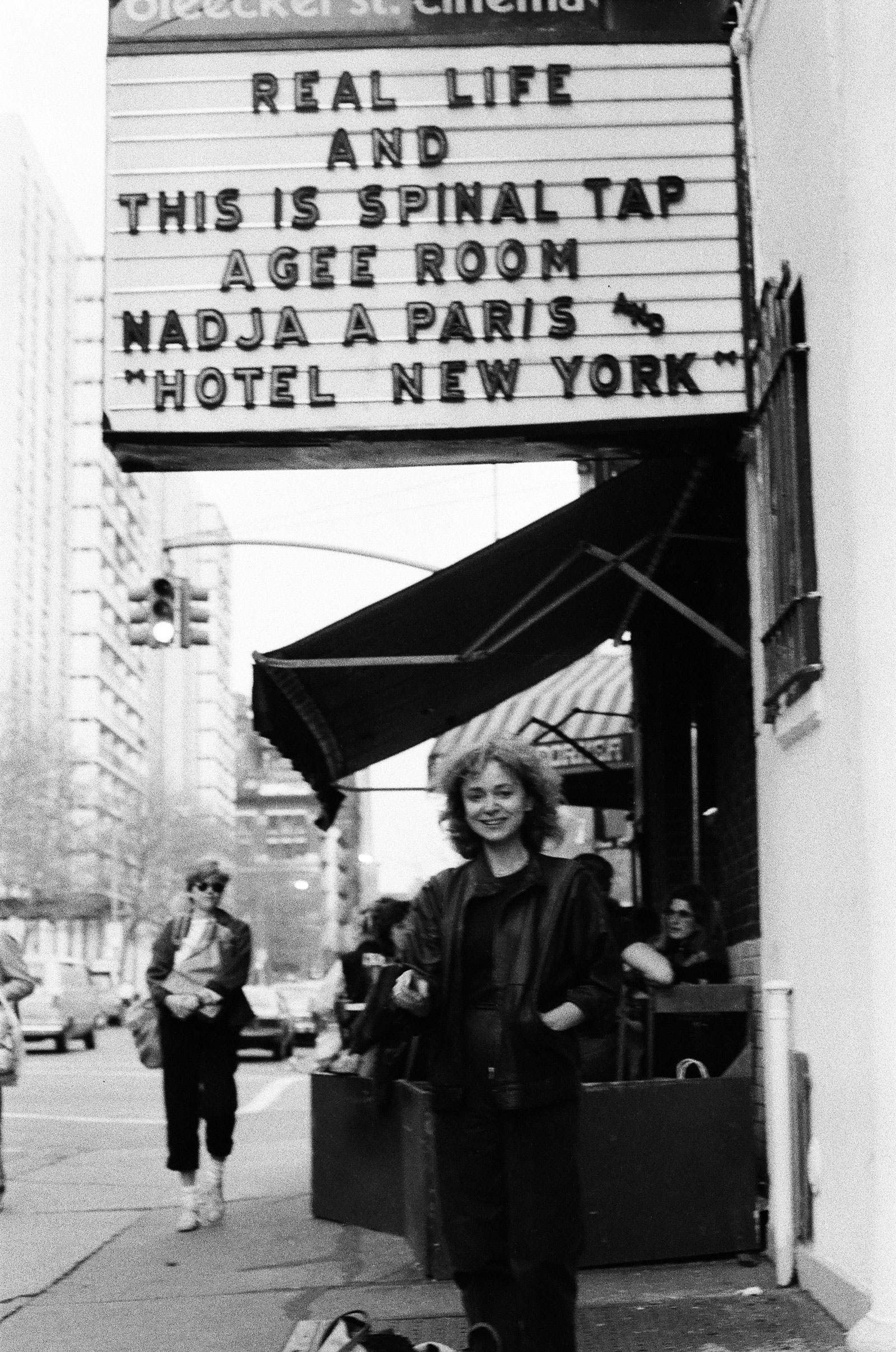

Years later, when I had left teaching in order to write full-time, I saw Nadja à Paris again at the Bleecker Street Cinema. I was afraid it would depress me the way old photos do, but instead I was touched by her. The girl, a child—me—was so thin and lonely looking, so sad in spite of the voice-over, which was all wisdom and lightness. You wanted to hug her, to console her about something.

In the lobby after the film, I unexpectedly ran into Carlos Clarens, a film critic and Néstor’s old friend from Cuba. Carlos had been with us that summer in Paris, as a film critic and an observer of our lives. We talked about this or that, Néstor’s fame, their quarrels with each other, mine with Néstor, and I asked him if I really looked that sad at the time. “Of course not,” Carlos laughed, “this is not a documentary, it’s Eric’s portrait of you, you mean you didn’t know that?”

Thanks to Carlos, we parted, the film and I. Over the years it had become like an official version of my life, obliterating the rest. While real life was bigger, it was chaotic and shapeless. The film had a structure, and I could see myself. But I had not been just lonely, I laughed as much.

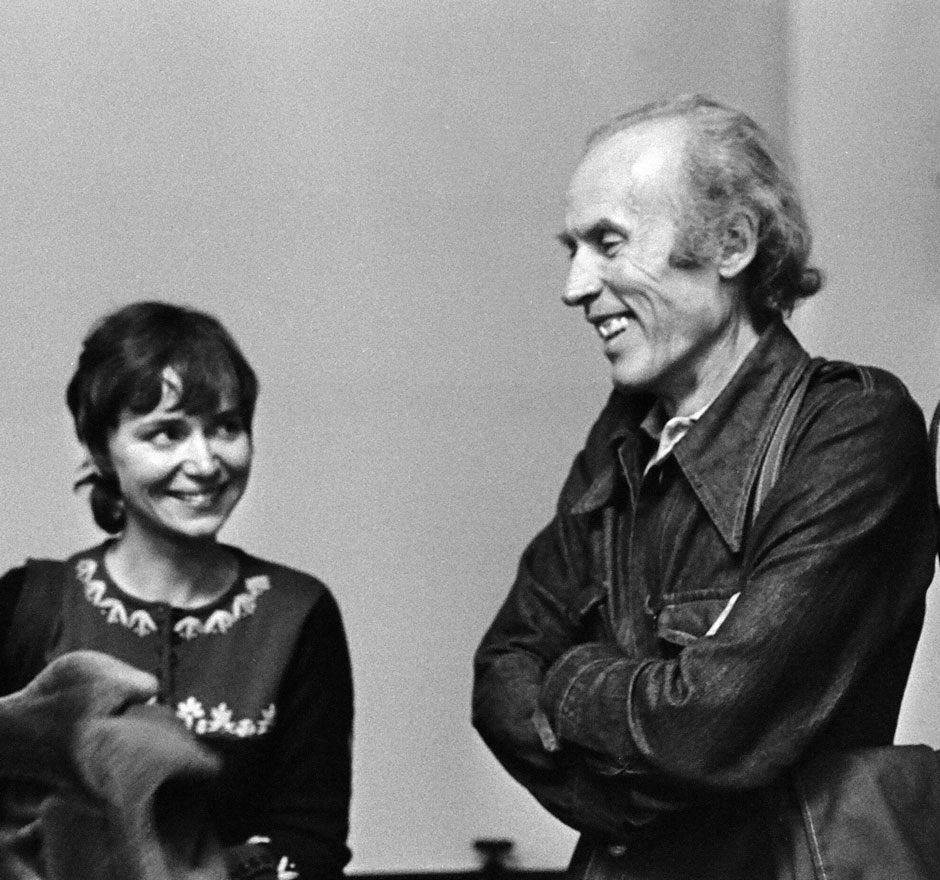

Eric and I never stopped seeing each other. Most likely I needed some distance to grow up, to get married and have a child. It’s funny how some of my “movement” buddies have become bankers and fancy lawyers, while Eric remained the same. His apartment was bigger, but not that big. He still had no phone. Neither one of us drove. And as a rebellion or resistance to the glut of fame, his films cost less and less to produce. A recent one had a crew of only two people plus him.

On some profound level, neither he nor I have changed, although I must have changed more. My hair is longer now, for one. He used to object to it in the beginning because he wanted me to remain forever the same, to appear always without notice on a Paris street.

On February 2, 2014, Nadja said of Rohmer: We were many things for each other, loving friends for sure, but for him I was always “Nadja” from André Breton’s novel. In 2010, I wanted to call him suddenly, but he had no phone, so I called his film company. “You found me once again,” he said. “I don’t come here often. Before, I found you.” He died three days later.

Part of a continuing NYR Daily series on life-changing films.