Inevitably, there was much self-congratulating last week when the Senate adopted by an overwhelming bipartisan majority a proposal that would allow Congress to vote on whether to approve a final nuclear deal with Iran. The adoption of the proposal was seen by many in Washington as a major shift in the tides of power. At last, Republican senators crowed, we’re asserting authority over an out-of-control president, whose alleged overreaches included the executive order relaxing immigration rules and Obamacare. Many Democrats, and not just those who are skeptical about an Iran deal, also felt that there was strong reason for Congress to have a say over such an important matter.

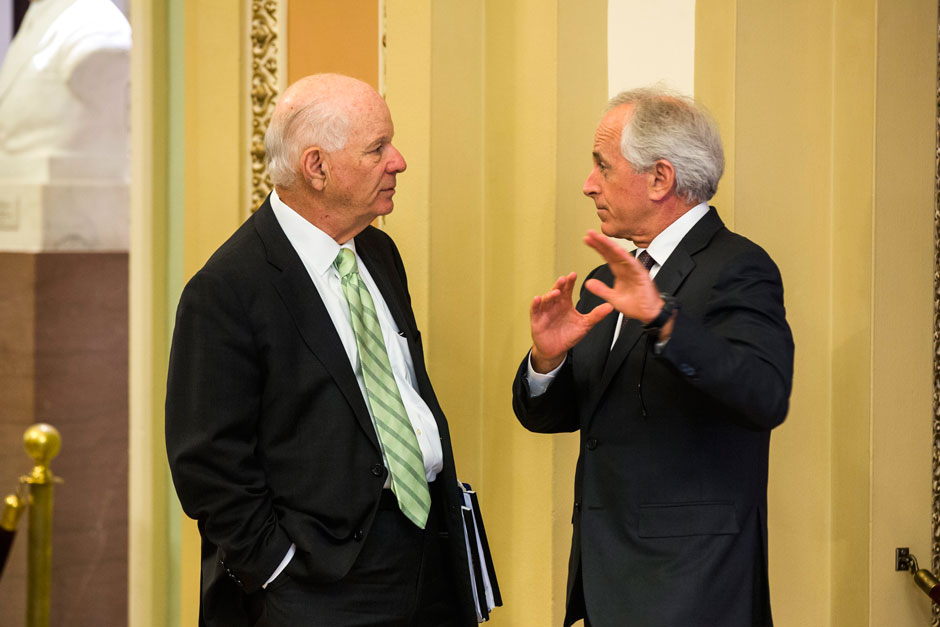

But the Corker-Cardin amendment—after Bob Corker, Republican of Tennessee, and Ben Cardin, Democrat of Maryland, the chairman and ranking members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee—was actually quite circumscribed in its reach and import. In fact, the particulars of the question of Congress’s role in a nuclear agreement with Iran made the new arrangement sui generis. For example, Congress is still at sea over how and whether to exert authority over the US’s expanded involvement in Iraq and Syria, not to mention Libya and Yemen (where our presence has been greater than advertised). As it was, since the Iran deal will be in the form of an executive agreement and not a treaty, there was no technical reason for congressional involvement; Congress had to create one over the objections of a president anxious to preserve his constitutional powers. (The White House also worried about signaling to the Iranians that it might not be able to live up to the deal.)

The rationale for Congress to get involved in approving the Iran deal is perhaps a unique one: that Congress had initiated some of the economic sanctions on Iran—the harshest ones yet—that would be lifted in connection with the agreement. Other sanctions, imposed by the administration and by the United Nations, remained beyond Congress’s reach. Technically, the president could waive the congressionally-imposed sanctions without Congress’s permission, since Congress had given authority over the sanctions to the executive branch. By almost unanimously passing Corker-Cardin, Congress would be saying that the president couldn’t waive Congress’s sanctions unless Congress approved the deal with Iran.

The Senate’s 98-1 vote in favor of the Corker-Cardin proposal belied the tensions and chance events that occurred along the way. Iran gets the politicians’ dander up like no other country, in part because of its known sponsorship of terrorist organizations, in particular Hezbollah and Hamas, as well as in a limited way the Houthi rebels in Yemen, who overthrew the US-backed government there. But perhaps most relevant with regard to the politics of the nuclear agreement is some of Iran’s highest officials having said that Israel shouldn’t exist. As was made clear in early March of this year, most Republicans and several Democrats support Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s view that probably no deal with Iran would be a good deal.

One of the Senate Democrats who supported the hard-line view toward Iran was Robert Menendez, who was Cardin’s predecessor as ranking Democrat (and former chairman) on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee but stepped down on April 1 after having been indicted for bribery and conspiracy. An earlier proposal by Menendez and Corker for a congressional say on a nuclear agreement with Iran was unacceptable to the administration. And last year the administration and arms control advocates had to beat back their proposal for more sanctions on Iran. That proposal, which Menendez supported, might well have derailed the negotiations.

The change in the Democratic leadership on the committee from Menendez to Cardin eased the situation for the president somewhat. Corker and Cardin, working with some other committee Democrats, painstakingly came up with a proposal that the president, who continued to resist the idea of a congressional voice on an agreement with Iran, would reluctantly swallow and the other Democrats could back. In the course of a series of conversations with the president, Cardin got across to him that Congress couldn’t be stopped from inserting itself in some way and that he himself supported congressional involvement. Cardin told me, “I explained to the president that it was about sanctions, not about Congress approving the deal.”

The approval or disapproval vote by Congress would be linked to whether the president could waive the sanctions; he couldn’t waive them until Congress approved the deal. If Congress were to disapprove the deal, that wouldn’t in itself sink it (a power Congress still didn’t have) but the fact that, under the law, the president couldn’t then lift the sanctions would have the same effect. This explanation of Congress’s involvement somewhat mollified the president.

Advertisement

Cardin also eased the situation for Obama by persuading Corker to drop one of the provisions he and Menendez had included requiring that the president certify in regular reports to Congress that Iran wasn’t backing terrorist acts. This was a poison pill, a requirement that the president clearly couldn’t meet and therefore would have doomed the agreement. Its presence in the Corker-Menendez proposal raised questions—as yet unanswered—as to Corker’s actual intent on a deal with Iran. Another important change that was made in the Corker-Menendez proposal was to cut by half the time for Congress to review the agreement—from sixty days to thirty.

But the fundamental difference between the Corker-Menendez proposal and the one arrived at between Corker and Cardin was that it switched the burden from the nuclear deal’s supporters having to find enough votes to approve it to the opponents of the deal having to find the votes to disapprove it. Wording was added that made it clear that Congress didn’t have to vote on such an agreement, in which case it would automatically go into effect. And then, in another significant change, if it did vote, the number of votes needed to disapprove a deal (depending on how the resolution is worded) was changed from a simple majority to sixty votes. Arms-control advocates had been very worried about the possibility that Congress could kill the deal by a simple majority. John Isaacs, of the Council for a Livable World, told me, “We would have lost.”

It remained the case that if Congress disapproved a deal and the president vetoed that resolution, Congress would have to cobble together thirty-four Senate votes to keep Congress from overriding a presidential veto. While some in the arms-control community are nervous about being able to produce those thirty-four votes, as Senator Chris Coons, of Delaware, said, “If the administration can’t persuade thirty-four senators of whatever party that this agreement is worth proceeding with, then it’s really a bad agreement.”

Since the Corker-Cardin proposal had been approved unanimously by the Foreign Relations Committee and represented a painfully wrought compromise, Democrats refrained from offering any amendments. But Republicans submitted over sixty amendments and Corker, Cardin, and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell were anxious to ward off any amendments that might undermine their proposal and had a chance of passing. Two particularly troubling amendments were Tom Cotton’s, which would require that Iran surrender all of its nuclear facilities before sanctions were waived—an obvious deal-killer –and an even more mischievous one by Marco Rubio, now a presidential candidate, which called on Iran to recognize Israel before an agreement could be implemented. That was as poisonous a pill as could be imagined, and Democrats definitely didn’t want to have to cast a vote that could be interpreted as less than faithful to Israel.

Not to be stopped by his majority leader and a respected committee chairman, Cotton took both by surprise through an unusual parliamentary maneuver that allowed his and Rubio’s amendments to be offered despite the leaders’ opposition. Cotton, the junior senator from Arkansas, has a way of going too far. His infamous letter to the Ayatollahs, aimed at sinking the talks and signed by forty-six other Republican senators and supported by a number of the party’s presidential candidates, ended as an embarrassment to his party, with several Republican Senators later expressing regret that they’d signed it. (John McCain explained that he and other senators hadn’t had time to think through the letter because they were fleeing town to avoid a snowstorm.)

Cotton’s audacious move on the Iran amendments threatened to undermine the carefully wrought deal between Corker and Cardin and between them and the White House. This was another thing that just wasn’t done—another boundary that the lean and hungry Cotton had no interest in observing. Neither McConnell nor Corker was amused. Cotton had put McConnell in a terrible position. When he took over the leadership of the Senate, McConnell had vowed not to shut off debate on amendments, as Harry Reid, the Democratic leader, had regularly done. Reid came under considerable criticism from the Republicans, but he had no choice but to invoke cloture time and again because McConnell couldn’t assure him that amendments offered by Republicans would be limited in number and scope and avoid “poison pills.”

Now McConnell was faced with the very same situation—except that the problem this time was coming from within his own ranks. Senate Democrats looked on in wonder and a certain bemusement at the spectacle. In pushing for votes on amendments that Corker and Cardin didn’t want to come before the Senate, Cotton and Rubio forced McConnell’s hand. Even if, as he’d indicated earlier, he wasn’t keen on a deal with Iran, McConnell couldn’t be the instrument of killing the celebrated compromise, much less undoing the work of his own party’s committee chairman. So, however reluctantly, and after a couple of days of trying but failing to get a voluntary agreement on which amendments could be offered, McConnell moved to invoke cloture.

Advertisement

By now the Corker-Cardin proposal had been sold to the senators as a way to ensure that Congress would have a voice on the deal with Iran. Therefore, all but six senators voted to shut off debate on the proposal (the holdouts had amendments they wanted to offer) and all but one—Tom Cotton—voted to adopt the Corker-Cardin proposal. One wonders how many times Cotton can strike a pose that’s so at odds with the interest of his colleagues and still have any effect in the Senate (though he may have bigger ambitions).

The next question is: What does the overwhelming acceptance of the Corker-Cardin compromise—the House is expected to follow—tell us about how an agreement reached with Iran will fare in Congress? The answer is: not very much. Much will depend on the nature and details of the final deal. Skeptical Democrats are particularly concerned, or so they say, about whether the provisions for inspection of suspected Iranian facilities will be thorough enough. Members of Congress are also concerned about how and when the sanctions would be lifted and how easy it will be to reimpose them. Word has spread from some wonks who are dubious about a deal with Iran that the final agreement won’t be nearly as attractive as the “framework” laid out by the president on April 2.

If that turns out to be so, Obama, who came under attack for raising some expectations about his health care plan too high (“If you like your plan you can keep it”), will face an outcry and big trouble on Capitol Hill. There’s no deep well of affection or trust for the president to draw on. In the Senate the Democrats can afford to lose only seven on their side. One arms-control proponent drew up a list of at least eleven Democrats whose votes couldn’t be taken for granted at this point. Another close observer of these events pointed out that, based on recent events in the Middle East, members are particularly reluctant to cast their votes for a foreign policy initiative that they cannot be sure will turn out well.

Chuck Schumer, presumably the next Democratic Senate leader, is known to have a hawkish view of Iran. Were Schumer to turn against a deal one can assume that other Democrats would join him. AIPAC, the hardline pro-Israel lobby that was known to have strong reservations about the negotiations, has been playing rope-a-dope: it wanted Corker-Cardin to be passed by Congress, and told its allies not to amend it, so as to be sure that Congress will have a chance to vote down an agreement it doesn’t like. But those who have deep misgivings or are opposed to a deal don’t have a workable alternative to at least postponing Iran’s development of a nuclear weapon for ten years (if the agreement works). So it’s possible that some skeptics will raise a lot of tough questions but in the end declare themselves satisfied to proceed with the deal.

I asked Richard Blumenthal, of Connecticut, one skeptical Democratic senator, what he thought were the prospects for approval of an actual deal in light of the Senate adoption of the Corker-Cardin proposal. He replied, “A million things can happen before we get to that.”