Much of what remains from antiquity is monumental: travertine temples, marble statues, bronze armor—these were built to last. But glass is fragile. It seems almost impossible to believe that a vessel that touched Roman lips two thousand years ago could be on display today.

“Ennion: Master of Roman Glass” was the Metropolitan Museum’s first ancient glass exhibit. This lovely small show presented the work of Ennion, the best-known glassmaker of antiquity. During his career in the first century AD, Ennion’s tablewares, prized for their crystalline elegance, decorated the homes of Rome’s upper and middle classes from Jerusalem to Venice. The show, which has traveled to the Corning Museum as part of an even larger exhibition on ancient glass, is a welcome reminder of just how keen the Romans were about precious glassware, from glass beads to brightly variegated millefiori glass—easy to forget, since so little of it survives.

Not all ancient glass, of course, was luxurious. The material was used for a range of purposes: storage of medicines, transporting cosmetics, tableware, jewelry, mosaics, and window panes. (A papyrus from Oxyrhynchus, in Roman Egypt, asks for six thousand pounds of glass in the construction of a public bath, presumably for the structure’s windows). The quality varied widely. Pliny the Elder wrote in his Natural History that glass had replaced gold and silver for drinking cups (in part because, unlike metal, glass did not alter the taste of what was within it) and described how two glass drinking cups sold for 6000 sesterces under Nero’s reign. As the glass industry expanded, however, vessels differed in appearance and cost—by the end of the first century, small bottles and containers had replaced fine tableware as the most common type of mold blown glass.

By the time Ennion ran his shop, glass was undergoing something of a renaissance. The invention of glass-blowing had changed the appearance of glassware and its prevalence. Where glass had previously been pressed into or around molds like clay to create beads, sculptures or small dishes, blowing into molds could produce objects that were both larger and more delicate. Glass-blowing also sped up the manufacturing process and rendered it cheaper. Blown glass vessels became mass-produced in shops that could put out 100 vessels a day.

Based in Sidon in modern-day Lebanon (famous, as Pliny noted, for “flatu figurare” or shaping glass by breath), Ennion was among the finest glassworkers of the period. As the exhibition repeatedly shows, he was less an original artist than an excellent craftsman. Many of his glass designs were common among glassmakers of the time. Like other artisans, he worked primarily with colored glass, particularly deep jeweled tones like cobalt and amber. His motifs—like honeycombs and leaves—were found in other contemporaneous vases.

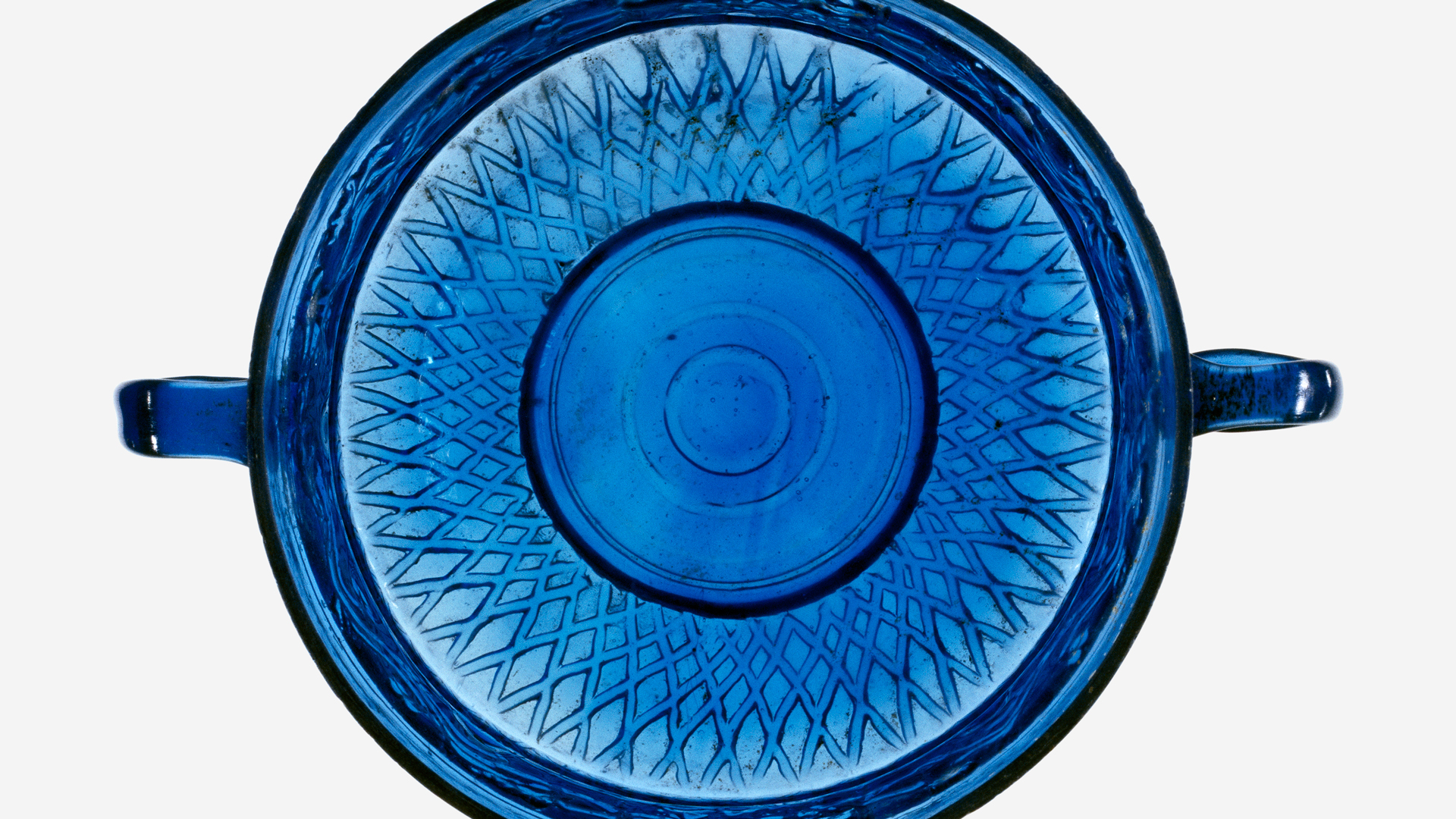

Yet his work has a balance and sense of proportion that makes it particularly appealing. As Christopher Lightfoot, the show’s curator, has observed, Ennion perfected the use of molds for making multiples of the same designs. His vessels often feature abstract, architectural and natural forms. One cup, several copies of which are on display at the Met, features a frieze with leaf-like bosses above a band of vertical stripes. Such stripes appear on much of his work; as the insightful catalog by Lightfoot notes, this particular pattern was likely copied by other artisans. The overall effect is simple yet graceful. A series of jugs in the middle of the exhibition further shows Ennion’s sense of harmony. Each has three horizontal bands across the body: a crosshatching pattern in the middle, with a leafy frieze above. Thin vertical stripes draw the eye down to the base, which tapers in and out. One particularly striking amphora has a handle from glass so opaque it looks almost like ivory or bone.

Advertisement

It was perhaps because of the pervasiveness of glassware and the large-scale glass trade that Ennion’s work seems so informed by commercial pressures. Ennion identified all of his work clearly and prominently; his signature appears not to the side but highlighted on large tablet-like labels that are fully integrated into his designs. Most of the works on exhibit show variations on his signature “Made by Ennion” or feature the artisan’s blessing for his work’s future owner. Indeed, as the exhibition shows, Ennion was not the only artisan with a name brand: a corner of the gallery compares his work to that of other known glass artists, Ennion’s rival Aristeas and the somewhat cruder Jason. And it’s possible that some of the coarser work that bears his name was made by an ancient fraudster.

A video loop on the wall shows how the glass was made. It was difficult, exacting work—glass must be kept at around 1000 degrees Celsius to shape, and must be heated several times as details like handles are added. But what the video doesn’t show is the equally hard work of preservation: how these cups and vases, fractured by time, were restored and, in one case, pieced back together with equal skill by conservators in museums and labs. The glassware on display is theirs too.

“Ennion: Master of Roman Glass” can be seen at the Corning Museum of Glass as part of its exhibition, “Ennion and his Legacy: Mold-Blown Glass from Ancient Rome,” on view through October 2015